40% Growth Then, 5% Growth Now — What We Must Learn Anew

When we talk about Jesus, Paul, and the rise of Christianity, we are not in the realm of myth or timeless stories. The New Testament roots its narrative in the concrete reigns of Roman emperors and the actions of their governors. Luke 3:1–2 names them explicitly. Tonight, we step into the reign of Tiberius Caesar, meet John the Baptist, examine Pontius Pilate, and see how all of this converges in the crucifixion of Jesus — an event so widely attested that even atheist historians treat it as one of the firmest facts of ancient history.

1. Tiberius: The Suspicious Recluse of Capri

Tiberius was Rome’s second emperor, ruling from AD 14 to 37. He was the stepson of Augustus, a capable general, and at first praised for discipline and stability. But over time, he became known for suspicion, cruelty, and retreat from public life.

Luke deliberately grounds the story of John the Baptist and Jesus in his reign:

“In the fifteenth year of the reign of Tiberius Caesar, Pontius Pilate being governor of Judea, and Herod being tetrarch of Galilee… the word of God came to John the son of Zechariah in the wilderness.”

—Luke 3:1–2 (c. AD 70–90, ESV)

The “fifteenth year” of Tiberius corresponds to AD 28 or 29.

Suetonius describes Tiberius’ withdrawal:

“He retired to Capri, and lived there for the most part, leaving the conduct of affairs to others, and only occasionally returning to the mainland.”

—Suetonius, Tiberius 40 (c. AD 110, Loeb)

Tacitus captures the regime’s climate:

“Under Tiberius, executions multiplied. Nobles were driven to suicide, men of rank were executed, the prisons were filled, and terror stalked the city.”

—Tacitus, Annals 6.19 (c. AD 115, Loeb)

Cassius Dio echoes the cruelty:

“He became savage and bloodthirsty, and put to death without trial all who were suspected.”

—Cassius Dio, Roman History 58.8 (c. AD 200–220, Loeb)

Suetonius also records the moral depravity remembered at Capri:

“He abandoned himself to scandalous and disgraceful excesses… gathering together companies of girls and perverts, and with every device of lewdness defiled the place.”

—Suetonius, Tiberius 43 (c. AD 110, Loeb, excerpted)

Ancient reports say this corruption even involved children groomed for him, and that he disposed of people brutally:

“Those who fell from favor, he would have thrown into the sea from the cliffs, and watch them perish.”

—Suetonius, Tiberius 62 (c. AD 110, Loeb)

This is why later generations called him Capri’s Monster. Roman historians remembered him not just as paranoid and cruel, but as morally depraved and willing to kill even children once he was finished with them.

Tiberius and the Title “Son of God”

Tiberius allowed — and even promoted — the cult of his adoptive father, Divus Augustus (“the Divine Augustus”). Coins of his reign often feature Augustus as a god.

- On these coins Augustus appears with the inscription DIVVS AVGVSTVS PATER (“the Divine Augustus, Father”).

- On the same coin, Tiberius is named TI CAESAR DIVI AVG F AVGVSTVS — which means “Tiberius Caesar Augustus, son of the Divine Augustus.”

This made Tiberius officially the “son of the divine Augustus” — a title printed on currency and circulated throughout the empire. Importantly, Tiberius did not call himself divine during his lifetime, but he claimed sonship of a god.

After his death in AD 37, the Senate debated whether to enroll him among the gods as Divus Tiberius. Suetonius notes that some argued for his deification, but because of his reputation as a cruel and depraved ruler, there was hesitation. Ultimately, he was not formally deified like Augustus.

Key Insight: Under Tiberius, the title “Son of God” was already political language, stamped on coins. Early Christians, when they confessed Jesus as the true “Son of God,” were directly challenging the imperial claims.

2. John the Baptist: A Voice Rome Couldn’t Ignore

Historians across the spectrum — Christian, Jewish, agnostic, and atheist — agree that John the Baptist is one of the most historically secure figures in the New Testament.

Why John’s life is considered historically certain:

- Multiple independent sources. John appears in all four Gospels and in Josephus (Antiquities 18.5.2).

- Criterion of embarrassment. The baptism of Jesus by John is a classic example. To say that Jesus — whom Christians confessed as sinless and greater than all prophets — nevertheless submitted to John’s baptism could look like John was spiritually superior. Bart Ehrman, an agnostic historian, puts it bluntly: “Jesus’ baptism by John the Baptist is one of the most certain things we know about Jesus.” (Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium, Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 106).

- Consistency of content. The Gospels and Josephus both describe John calling people to repentance, righteousness, and baptism as an outward sign of an already-transformed life.

- Cultural plausibility. Prophets who attracted crowds were viewed as dangerous under Roman rule.

- Josephus’ detailed confirmation. Josephus provides a long, independent account of John’s preaching, his imprisonment at Machaerus, and his execution by Herod Antipas, the son of Herod the Great and tetrarch of Galilee and Perea (4 BC–AD 39).

Josephus records:

“Now some of the Jews thought that the destruction of Herod’s army came from God, and that it was a very just punishment for what he had done against John, who was called the Baptist. For Herod had killed this good man, who had exhorted the Jews to lead righteous lives, to practice justice toward their fellows and piety toward God, and so doing join in baptism. In his view this was a necessary preliminary if baptism was to be acceptable to God. They must not employ it to gain pardon for whatever sins they committed, but as a consecration of the body, implying that the soul was already cleansed by right behavior. And when others too joined the crowds about him, because they were aroused to the highest degree by his sermons, Herod became alarmed. Eloquence that had so great an effect on mankind might lead to some form of sedition, for it looked as if they would do everything he counseled. Herod decided, therefore, that it would be much better to strike first and be rid of him before any insurrection might develop, than to wait for an upheaval, get involved in a difficult situation, and see his mistake. And so, because of Herod’s suspicion, John was sent in chains to Machaerus, the stronghold that we have previously mentioned, and there put to death. The Jews, however, were of the opinion that the destruction of his army was sent as a punishment upon Herod, and a mark of God’s displeasure with him.”

—Josephus, Antiquities 18.5.2 §116–119 (c. AD 93, Loeb)

Key Insights:

- The bolded section shows how closely Josephus’ description of John matches the Gospels: baptism was only valid if accompanied by righteous works.

- The Gospels record John saying the same thing: “Bear fruits worthy of repentance” (Luke 3:8).

- Both Josephus and the Gospels show John as a preacher whose eloquence stirred the crowds and made rulers nervous.

- Herod Antipas executed John not for violence but for influence — the people were ready to “do everything he counseled.”

- Even Josephus, no friend to Christianity, confirms that John’s execution was seen as unjust and provoked divine judgment.

Because of this convergence — Gospel tradition, embarrassing detail, Josephus’ independent testimony, and the cultural setting — John the Baptist is regarded by virtually all historians as one of the most certain figures of Jesus’ world.

3. Pontius Pilate: Rome’s Reckless Governor

Pontius Pilate served as prefect of Judea from AD 26–36, appointed by Tiberius, likely through the influence of Sejanus. Prefects of equestrian rank governed Judea — a small but volatile province where Jewish nationalism, deep piety, and Roman imperial control collided.

Philo of Alexandria, writing within a decade of Pilate’s dismissal (c. AD 41–42), paints him in the harshest terms:

“Pilate was a man of inflexible, stubborn, and cruel disposition, and he caused trouble by his venality, his violence, his thefts, his assaults, his abusive behavior, his frequent executions of untried prisoners, and his endless savage ferocity.”

—Philo, Embassy to Gaius §301 (c. AD 41–42, Loeb)

“His corruption, his acts of insolence, his rapine, his habit of insulting people, his cruelty, his continual murders of people untried and uncondemned, and his never-ending and most grievous brutality.”

—Philo, Embassy to Gaius §302 (c. AD 41–42, Loeb)

This matches the Gospels’ picture of Pilate: a man who caves to pressure, indifferent to justice, quick to violence, and willing to condemn an innocent man for expedience.

The Golden Shields Affair (Philo, c. AD 26–27)

“Pilate, who had been appointed prefect of Judaea, displayed the shields in Herod’s palace in the Holy City. They bore no image — only an inscription. But when the people learned what had been done, and realized that their laws had been trampled underfoot, they petitioned Pilate to remove the shields. He steadfastly refused. Then they took the matter to Tiberius, who was indignant that Pilate had dared to offend religious sentiments and ordered him by letter to remove the shields immediately and transfer them to Caesarea.”

—Philo, Embassy to Gaius §§299–305 (c. AD 41–42, Loeb)

Key Insight: This was one of Pilate’s first provocations. Even without images, inscriptions in the Temple area were offensive. Pilate refused to compromise until the Jews appealed directly to Tiberius. Rome itself forced Pilate to back down, showing both his arrogance and his weakness.

The Standards Incident (Josephus, c. AD 26–27)

“But now Pilate, the procurator of Judaea, brought into Jerusalem by night and under cover the effigies of Caesar that are called standards. The next day this caused a great uproar among the Jews. Those who were shocked by the incident went in a body to Pilate at Caesarea and for many days begged him to remove the standards from Jerusalem. When he refused, they fell to the ground and remained motionless for five days and nights. On the sixth day Pilate took his seat on the tribunal in the great stadium and summoned the multitude, as if he meant to grant their petition. Instead, he gave a signal to the soldiers to surround the Jews, and threatened to cut them down unless they stopped pressing their petition. But they threw themselves on the ground and bared their necks, shouting that they would welcome death rather than the violation of their laws. Deeply impressed by their religious fervor, Pilate ordered the standards to be removed from Jerusalem.”

—Josephus, Antiquities 18.3.1 §55–59 (c. AD 93, Loeb)

Key Insight: Pilate smuggled Caesar’s images into Jerusalem under cover of night. Thousands of Jews protested nonviolently, offering their necks to the sword rather than accept idolatry. Pilate again provoked needlessly, then caved under pressure. This shows both his disregard for Jewish law and his fear of mass unrest.

The Aqueduct Massacre (Josephus, c. AD 30–31)

“Pilate undertook to bring a stream of water to Jerusalem, and did it with the sacred money of the treasury… many ten thousands of the people got together, and made a clamour against him… So he ordered a great number of his soldiers to have their weapons concealed under their garments, and sent them to a place where they might surround them. He bade the Jews himself go away; but they boldly casting reproaches upon him, he gave the soldiers that signal which had been beforehand agreed on; who laid upon them much greater blows than Pilate had commanded them, and equally punished those that were tumultuous, and those that were not. Nor did they spare them in the least; and since the people were unarmed, and were caught by men prepared for what they were about, there were a great number of them slain by this means, and others of them ran away wounded. And thus an end was put to this sedition.”

—Josephus, Antiquities 18.3.2 §60–62 (c. AD 93, Loeb); cf. War 2.9.4 §175–177 (c. AD 75, Loeb)

Key Insight: This incident occurred around the same time as Jesus’ crucifixion. Pilate raided the Temple treasury for a building project, outraging the people. When they protested, he ordered disguised soldiers to massacre them. This matches the Pilate of the Gospels: willing to shed innocent blood if he feared disorder.

The Samaritan Slaughter and Recall (Josephus, AD 36)

“But the Samaritan multitude, being hindered from going up by Pilate and having many of them slain, … Vitellius… ordered Pilate to go to Rome, to answer before the emperor to the accusations of the Samaritans. So Pilate, when he had tarried ten years in Judea, made haste to Rome… but before he could get to Rome, Tiberius was dead.**”

—Josephus, Antiquities 18.4.1 §85–89 (c. AD 93, Loeb)

Key Insight: This slaughter ended Pilate’s career. He massacred Samaritans on Mount Gerizim, and the governor of Syria intervened. Pilate was recalled to Rome in disgrace, but Tiberius died before his trial. His decade of rule left a legacy of provocation, violence, and weakness.

Key Insights Summarized:

- Philo (c. AD 41–42), writing almost immediately after Pilate’s rule, confirms his reputation for brutality and corruption.

- Josephus (c. AD 75–93) gives multiple episodes that illustrate Pilate’s pattern: provoke → resistance → back down or slaughter.

- The Gospels’ account of Pilate condemning Jesus out of weakness and expedience fits perfectly with this record.

- By AD 30, when Jesus was crucified, Pilate was already known for religiously offensive acts and brutal crackdowns.

This is the prefect who presided over the trial of Jesus.

4. Jesus Crucified Under Tiberius

Even non-Christian sources confirm the crucifixion of Jesus. One of the most important comes from the Roman historian Tacitus, writing in the early 2nd century.

“Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilatus, and the pernicious superstition was checked for a moment, only to break out once more, not merely in Judea, the home of the disease, but in the capital itself, where all things horrible or shameful in the world collect and find a vogue.”

—Tacitus, Annals 15.44 (c. AD 115, Loeb)

Key Insights:

- Tacitus confirms that Jesus was executed in the reign of Tiberius, by the governor Pontius Pilate.

- Tacitus calls Christianity a “pernicious superstition,” showing his hostility, yet he still records the fact of Jesus’ death.

- He says the movement was “checked for a moment” — Rome thought crucifixion had ended it. Instead, it “broke out once more” and even reached Rome itself.

- For Romans, crucifixion was supposed to erase a man’s memory forever. But in the case of Jesus, it became the foundation of a worldwide movement.

5. Mass Revolts vs. Jesus’ Isolation

In the decades before and after Jesus’ crucifixion, Rome responded to uprisings in Judea with mass crucifixions and bloodshed.

4 BC: After the Death of Herod the Great

“Varus sent part of his army into the country, to seek out the authors of the revolt; and when they were discovered, he punished some of them that were most guilty, and some he dismissed. Now the number who were crucified on this account were two thousand.”

—Josephus, War 2.5.2 §75 (c. AD 75, Loeb)

Key Insight: Rome crucified 2,000 Jews at once after Herod’s death, using mass execution to terrify the nation.

AD 6: The Revolt of Judas the Galilean

“Yet was there one Judas, a Gaulonite, of a city whose name was Gamala, who, taking with him Saddok, a Pharisee, became zealous to draw them to a revolt, who both said that this taxation was no better than an introduction to slavery, and exhorted the nation to assert their liberty. … This bold attempt at innovation brought the nation to ruin.”

—Josephus, Antiquities 18.1.1 §4–6 (c. AD 93, Loeb)

Key Insight: Judas called taxation slavery and stirred revolt. Josephus says this “brought the nation to ruin.” Later, his sons were crucified by Rome, showing the empire’s relentless vengeance against such movements.

AD 30–31: Pilate’s Aqueduct Massacre

“…many ten thousands of the people got together, and made a clamour against him… he gave the soldiers that signal which had been beforehand agreed on… Nor did they spare them in the least… there were a great number of them slain by this means, and others of them ran away wounded.”

—Josephus, Antiquities 18.3.2 §60–62 (c. AD 93, Loeb)

Key Insight: Pilate slaughtered crowds of unarmed Jews when they protested his misuse of Temple funds.

AD 36: Pilate’s Samaritan Slaughter

“But the Samaritan multitude, being hindered from going up by Pilate and having many of them slain, … Vitellius… ordered Pilate to go to Rome, to answer before the emperor to the accusations of the Samaritans. So Pilate, when he had tarried ten years in Judea, made haste to Rome… but before he could get to Rome, Tiberius was dead.**”

—Josephus, Antiquities 18.4.1 §85–89 (c. AD 93, Loeb)

Key Insight: Pilate massacred Samaritans on Mount Gerizim in AD 36. The bloodshed was so severe that the governor of Syria removed Pilate from power.

AD 44–46: The Revolt of Theudas

“…a certain magician, whose name was Theudas, persuaded a great part of the people to take their effects with them, and follow him to the river Jordan… However, Fadus… sent a troop of horsemen out against them; who, falling upon them unexpectedly, slew many of them, and took many of them alive. They also took Theudas alive, and cut off his head, and carried it to Jerusalem.”

—Josephus, Antiquities 20.5.1 §97–99 (c. AD 93, Loeb)

Key Insight: Theudas and his followers were destroyed. He was beheaded, and many were killed or captured.

AD 66–70: The Jewish War

“So the soldiers… nailed those they caught, one after one way, and another after another, to the crosses, by way of jest; when their multitude was so great, that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses wanting for the bodies.”

—Josephus, War 5.11.1 §446 (c. AD 75, Loeb)

Key Insight: During the siege of Jerusalem, crucifixion became a grotesque spectacle. So many were executed that they ran out of wood for crosses.

Jesus’ Crucifixion in Contrast

Against this backdrop, the crucifixion of Jesus in AD 30 stands out as unique.

- In times of revolt, Rome crucified thousands at once.

- Yet in Jesus’ case, only he was crucified.

- His followers were not executed; they were scattered and spared.

The Gospels emphasize how alone he was at the end:

- “And they all left him and fled.” (Mark 14:50, c. AD 70)

- “Then all the disciples left him and fled.” (Matthew 26:56, c. AD 80s)

- “The Lord turned and looked at Peter… And he went out and wept bitterly.” (Luke 22:61–62, c. AD 70–90)

- “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34, c. AD 70)

How many were there?

- At minimum: 3–4 named women (Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James/Joses, Salome or the mother of Zebedee’s sons), plus the beloved disciple.

- Likely range: 4–5 people for sure, possibly up to a dozen if Luke’s “all his acquaintances” implies more.

Key Insight: Unlike Judas the Galilean, Theudas, or the rebels in the Jewish War, Jesus died alone, abandoned by nearly everyone. Rome crucified thousands, but on that Friday Pilate crucified one man, and in that one death the movement lived on.

Reflection Questions

- Why crucify only Jesus?

- Rome’s normal practice was to crush movements with mass executions. Why do you think Pilate singled out Jesus but let his followers go free?

- What if all the disciples had died with him?

- How might the early Christian movement have been different if Jesus’ closest followers had been rounded up and killed as well? Would the message have spread? Would we even be talking about it today?

6. Roman Disgust for Crucifixion

For Romans, crucifixion was not only brutal; it was considered the most degrading, shameful punishment possible. It was designed for slaves, rebels, and the lowest criminals — never for Roman citizens.

Cicero on Crucifixion (70 BC)

“To bind a Roman citizen is a crime, to scourge him is an abomination, to slay him is almost an act of murder; to crucify him is—what? There is no fitting word that can possibly describe so horrible a deed.”

—Cicero, Against Verres 2.5.66 (c. 70 BC, Loeb)

“But the very mention of the cross should be far removed not only from a Roman citizen’s body, but from his mind, his eyes, his ears.”

—Cicero, Against Verres 2.5.168 (c. 70 BC, Loeb)

Key Insight: Cicero said crucifixion was so vile that it should not even be mentioned in polite Roman society. For a Roman citizen, the cross was unthinkable.

Seneca on Crucifixion (c. AD 65)

“Can anyone be found who would prefer wasting away in pain dying limb by limb, or letting out his life drop by drop, rather than expiring once for all? Can any man be found willing to be fastened to the accursed tree, long sickly, already deformed, swelling with ugly weals on shoulders and chest, and drawing the breath of life amid long-drawn-out agony?”

—Seneca, Epistle 101.14 (c. AD 65, Loeb)

Key Insight: Seneca captures the drawn-out torture of crucifixion — a slow, humiliating, agonizing death that deformed the body and crushed the spirit.

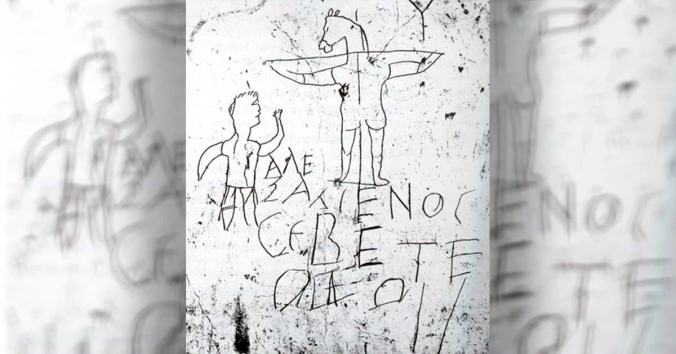

The Alexamenos Graffito (late 1st-3rd century AD)

Scratched into the plaster wall of a building on the Palatine Hill in Rome, directly connected with the imperial palace, is the earliest surviving caricature of Christian worship. The structure is usually called the Paedagogium because it may have housed imperial page boys — though some scholars think it functioned as barracks or service quarters. Whatever its exact purpose, it was part of daily life around the emperor’s residence.

The graffito, dated between the late first and third centuries, depicts a man with hands raised in prayer before a crucified figure with a donkey’s head. Beneath it is scrawled:

“Alexamenos worships his god.”

Key Insight: This is the earliest known depiction of the crucifixion of Jesus. It was meant as mockery: to Romans, worshipping a crucified man was ridiculous, even contemptible. The donkey’s head was a common insult — suggesting stupidity and folly. This graffito shows that Roman ridicule of the cross was alive and well by the early centuries.

Why This Matters for Christianity

- Crucifixion was meant to erase memory, to obliterate a person’s honor and legacy.

- Yet Christianity placed the crucifixion of Jesus at the very center of its message.

- What Romans thought too shameful to speak of, Christians proclaimed as the very power of God.

- The fact that Christians endured this shame and scorn only strengthens the historical case that they truly believed Jesus was risen and exalted.

7. Modern Skepticism of the Gospel Accounts

Skeptics such as Bart Ehrman argue that the Gospels are filled with contradictions and discrepancies. Ehrman often highlights 30–40 examples, while harsher critics expand the list to 70 or more. These examples are used to shake confidence in Scripture, especially among students encountering them for the first time.

Here are the 10 most significant contradictions skeptics emphasize:

Macro-Level Contradictions (Big Picture)

- Birth Narratives & Genealogies (Matthew vs. Luke):

- Matthew: Jesus born under Herod the Great (d. 4 BC). Wise men visit. Family flees to Egypt. Joseph’s father is Jacob.

- Luke: Jesus born during the census under Quirinius (AD 6). Shepherds visit. Family returns to Nazareth. Joseph’s father is Heli.

- This creates both a 10-year difference in dating and a different ancestry for Joseph.

- Trips to Jerusalem (Synoptics vs. John):

- Synoptics: One final climactic trip to Jerusalem → ministry about 1 year.

- John: At least three Passovers → ministry about 3 years.

- Passover Meal & Crucifixion Timing:

- Synoptics: Jesus eats the Passover meal on Thursday night. Arrested that night. Crucified on Friday — the first day of Passover (15th of Nisan).

- John: Jesus is crucified on Friday — the Day of Preparation (14th of Nisan), at the hour the lambs were slaughtered. In this account he does not eat the Passover meal.

- Both agree it was Friday. The disagreement is whether that Friday was Passover itself (Synoptics) or the day before Passover (John).

- Cleansing of the Temple:

- Synoptics: At the end of Jesus’ ministry, sparking his arrest.

- John: At the beginning of his ministry, right after the wedding at Cana.

- Post-Resurrection Instructions:

- Matthew 28: Jesus directs disciples to Galilee.

- Luke 24 / Acts 1: Jesus tells them to stay in Jerusalem.

- John 20–21: Jesus appears in both Jerusalem and Galilee.

Micro-Level Contradictions (Narrative Details)

- Jairus’ Daughter (Mark 5:22–23 vs. Matthew 9:18):

- Mark: Jairus says his daughter is “at the point of death.” She dies later.

- Matthew: Jairus says she is “already dead.”

- Centurion’s Servant (Matthew 8:5–7 vs. Luke 7:1–7):

- Matthew: The centurion comes personally to Jesus.

- Luke: The centurion never comes; he sends Jewish elders.

- The Call of the First Disciples (Mark 1:16–20 vs. Luke 5:1–11):

- Mark: Jesus calls fishermen while they cast nets — they follow immediately.

- Luke: Jesus first performs the miraculous catch of fish.

- Blind Men near Jericho (Mark 10:46 vs. Matthew 20:29–30):

- Mark: Jesus heals one blind man (Bartimaeus).

- Matthew: Jesus heals two blind men.

- The Women at the Tomb (Mark 16:5 vs. Luke 24:4 vs. John 20:12):

- Mark: One young man (angel).

- Luke: Two men in dazzling apparel.

- John: Two angels seated where the body had been.

Key Insights

- These contradictions are real — we don’t deny them.

- They demonstrate that the Gospels are independent voices, not colluded copies.

- They arose in different places and times (Galilee, Jerusalem, Asia Minor, Rome), sometimes decades apart.

- Despite these differences, they all converge on the same core story:

- Jesus was baptized by John.

- He preached and clashed with leaders.

- He was crucified under Pilate.

- His followers proclaimed him risen.

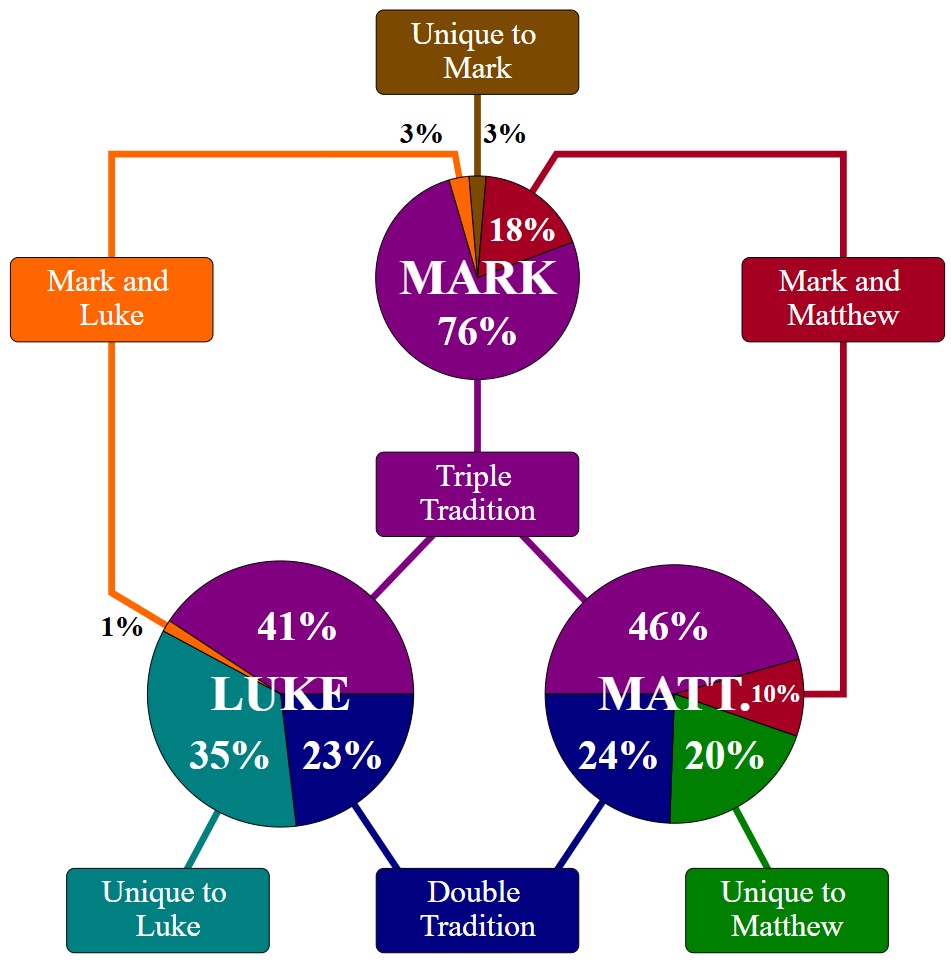

8. The Synoptic Problem, Gospel Dating, and the Centrality of the Passion

After hearing the skeptic’s case, it’s important to understand how the Gospels actually came together and why their differences make them stronger as historical witnesses, not weaker.

The Synoptic Problem: How the Gospels Relate

Scholars call Matthew, Mark, and Luke the “Synoptic Gospels” because they share so much in common. Most agree:

- Mark was written first.

- Matthew and Luke used Mark plus their own unique material.

- They also shared a second source (called “Q” by many scholars), a collection of Jesus’ sayings.

- John is completely independent, with 90% unique content.

This means the story of Jesus rests on at least five independent streams of tradition: Mark, Q (the “double tradition” below), Matthew’s unique material, Luke’s unique material, and John.

Key Insight: The differences skeptics point to show the Gospels did not copy from one master story. They arose independently from multiple witnesses and communities — and yet they converge on the same core events.

Clear Examples of Shared Wording

Even though the Gospels are independent, sometimes the overlap is so close it proves Matthew and Luke had Mark in front of them.

Example 1: Healing of Peter’s Mother-in-Law

- Mark 1:30–31 – “Simon’s mother-in-law lay ill with a fever… He came and took her by the hand and lifted her up, and the fever left her, and she began to serve them.”

- Matthew 8:14–15 – “He saw Peter’s mother-in-law lying sick with a fever. He touched her hand, and the fever left her, and she rose and began to serve him.”

- Luke 4:38–39 – “Simon’s mother-in-law was ill with a high fever… He stood over her and rebuked the fever, and it left her, and immediately she rose and began to serve them.”

Key Insight: Mark and Matthew are almost word-for-word; Luke is close with only slight variation. This is the kind of passage that shows literary dependence.

Example 2: Feeding of the 5,000

- Mark 6:41 – kai labōn tous pente artous kai tous duo ichthuas (“and taking the five loaves and the two fish…”)

- Matthew 14:19 – kai labōn tous pente artous kai tous duo ichthuas (“and taking the five loaves and the two fish…”)

- Luke 9:16 – labōn de tous pente artous kai tous duo ichthuas (“and taking the five loaves and the two fish…”)

Key Insight: Even if you can’t read Greek, you can see the phrase labōn tous pente artous kai tous duo ichthuas — “taking the five loaves and the two fish” — is virtually identical in all three accounts. This shows Matthew and Luke were drawing from Mark (or a common source) directly.

Gospel Dating: Skeptical Assumptions vs. Earlier Evidence

Critical scholars usually date the Synoptics after AD 70. Why? Because Jesus predicts the destruction of Jerusalem, and they assume prophecy is impossible — so the Gospels must have been written after the fact.

But there are strong reasons to believe the Gospels were written earlier:

- Paul’s Letters (c. AD 50s): Paul already quotes sayings of Jesus that appear in the Gospels, showing the traditions were circulating decades earlier.

- 1 Corinthians 7:10–11 – “To the married I give this charge (not I, but the Lord): the wife should not separate from her husband… and the husband should not divorce his wife.”

- Echoes Mark 10:11–12 / Matthew 19:6: “Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery… What God has joined together, let not man separate.”

- 1 Corinthians 9:14 – “In the same way, the Lord commanded that those who proclaim the gospel should get their living by the gospel.”

- Echoes Luke 10:7 / Matthew 10:10: “The laborer deserves his wages.”

- 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 – “The Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread… ‘This is my body… This cup is the new covenant in my blood.’”

- Echoes Luke 22:19–20 / Matthew 26:26–28 / Mark 14:22–24: “This is my body, which is given for you… This cup is the new covenant in my blood.”

- 1 Corinthians 7:10–11 – “To the married I give this charge (not I, but the Lord): the wife should not separate from her husband… and the husband should not divorce his wife.”

- The 1 Corinthians 15 Creed (early 30s):

- “Christ died for our sins… he was buried… he was raised on the third day… he appeared to Cephas, then to the Twelve…”

- Bart Ehrman (agnostic NT scholar): “An early tradition, probably going back to the early 30s CE, just a few years after Jesus’ death.” (Did Jesus Exist?, 2012, p. 132).

- Gerd Lüdemann (atheist NT scholar): “The elements in the tradition are to be dated to the first two years after the crucifixion of Jesus.” (The Resurrection of Jesus, 1994, p. 38).

- Key Insight: Even skeptics admit this creed goes back to the early 30s. It confirms the Gospel core: Jesus’ death, burial, resurrection, and appearances.

- The Christ Hymn (Philippians 2:6–11, early 30s):

- “He humbled himself by becoming obedient to the point of death, even death on a cross. Therefore God has highly exalted him and bestowed on him the name that is above every name.”

- James D.G. Dunn (critical scholar): “A tradition formulated and used in the worship of the earliest church, probably within a few years of the crucifixion.” (Christology in the Making, 1980, p. 114).

- Key Insight: Like the 1 Cor 15 creed, this hymn dates to the early 30s. Christians were already singing about Jesus’ crucifixion and exaltation as Lord.

- The Ebionites (a heretical Christian group):

- Early church fathers reported that the Ebionites, who fled to Pella around AD 70, were already altering Matthew’s Gospel to suit their theology.

- That means Matthew had to exist before AD 70 — which also pushes Mark earlier.

Key Insight: The skeptical dating rests on rejecting prophecy, not historical evidence. When we look at Paul’s letters, the early creed in 1 Corinthians 15, the Christ Hymn in Philippians 2, and the Ebionites tampering with Matthew before AD 70 — the evidence shows that the Gospels and their message were already circulating within living memory of Jesus’ death.

Unity Despite Diversity

- Later, John’s Gospel (c. AD 90s) was written from a different community and geography, with 90% unique material.

- And yet John confirms the same core truths as the Synoptics: Jesus was crucified, raised, and exalted as Lord.

Key Insight: The diversity of the Gospels is striking, but their agreement on the essentials is even more powerful. Independent voices, written in different decades and places, converge on the same unshakable core.

The Passion as the Center of Every Gospel

Despite their differences, all four Gospels converge on one point: Jesus’ death and resurrection are the heart of the story.

| Gospel | % of Book on Last Week | Where Passion Focus Begins | % of Book from That Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matthew | 36% (ch. 21–28) | Ch. 16 (“Sign of Jonah,” first passion predictions) | 51% (ch. 16–28) |

| Mark | 34% (ch. 11–16) | Ch. 8 (first passion prediction) | 55% (ch. 8–16) |

| Luke | 27% (ch. 19–24) | Ch. 9 (“sets his face toward Jerusalem”) | 65% (ch. 9–24) |

| John | 39% (ch. 12–21) | From the start (“Lamb of God,” 1:29; “Destroy this temple”) | 100% |

Key Insight: Up to two-thirds of the Synoptics, and virtually all of John, is oriented toward Jesus’ death and resurrection. No matter their differences, the cross is central in every Gospel.

9. The Burial Question

Skeptics like Bart Ehrman argue that Jesus’ body was probably left on the cross to rot or thrown into a common grave. They emphasize that part of the shame of crucifixion was being denied burial. But when we examine both the archaeology and the Jewish context, the burial of Jesus becomes historically plausible — even likely.

Archaeological Evidence

Out of hundreds of thousands of crucifixions in the Roman world, four sets of skeletal remains confirm that some victims were buried:

- Yehohanan (Jerusalem, before AD 70):

- Found in 1968 in a family tomb at Giv’at ha-Mivtar, Jerusalem.

- Heel bone pierced by an iron nail, with legs crushed (crurifragium).

- Confirms Jewish crucifixion victims could be buried quickly, as Jewish law required, with legs broken to hasten death before sundown.

- Significance: Matches exactly the Gospel detail in John 19:31–32 — Jewish law demanded burial the same day.

- Skeleton 4926 (Fenstanton, England, AD 130–360):

- Discovered in 2017 in a Roman cemetery.

- Heel bone pierced by a nail.

- First confirmed crucifixion victim in Roman Britain.

- Significance: Shows burial of crucifixion victims also happened outside Judea.

- Gavello, Italy (1st–2nd century AD):

- Heel bone with hole, no nail preserved.

- Poorer preservation, but consistent with crucifixion.

- Significance: Suggests burial after crucifixion in northern Italy.

- Mendes, Egypt (Roman era):

- Skeleton with hole in foot bone and above the knee, indicating nails and leg trauma.

- Legs were crushed.

- Significance: Confirms practices of nailing and leg-breaking extended beyond Judea.

Key Insight: Though rare in the archaeological record, these four finds prove crucifixion victims were sometimes buried — including Jews in Jerusalem before AD 70.

Why the Evidence Is Rare

Romans crucified thousands across the empire — Josephus alone records mass crucifixions of 2,000 in 4 BC and so many in AD 70 that there was no room for the crosses or crosses for the bodies. Yet only four skeletons with crucifixion marks have been identified.

Why so few?

- Most victims were tied with ropes rather than nailed. Rope leaves no trace on bone.

- Many who were nailed were pierced through soft tissue (hands, wrists, ankles) rather than through bone, so no permanent mark was left.

- Nails were valuable; Romans often pulled them out and reused them.

- Bodies of the crucified were often left exposed or thrown into shallow graves where bones did not preserve.

Key Insight: The four skeletons we have are unique cases where the nail pierced bone (creating visible holes). They prove crucifixion victims could be buried — and that some were. The rarity of finds reflects the method of crucifixion, not its improbability.

Jewish Law and Tradition

- Deuteronomy 21:22–23 — “His body shall not remain all night upon the tree, but you shall bury him the same day.”

- Dead Sea Scrolls (11Q Temple, 4QpNahum): Apply this law directly to crucifixion.

- m.Sanhedrin 6:5: “Anyone who delays burial to the next day has transgressed a commandment.”

- Rabbi Moses ben Nahman (1194–1270): Even the worst criminal deserves burial: “Do not leave his body hanging… someone who is hanged is more accursed and degraded than anyone else.”

- Targum Pseudo-Jonathan: “It is an affront to God to crucify a man… bury him.”

Key Insight: Burial of executed criminals was a matter of Jewish law. Roman governors in Judea often made concessions to Jewish customs, especially in Jerusalem, to avoid unrest.

Jesus’ Unique Situation

- In Jewish revolts, Rome crucified thousands at once — no one could be buried properly.

- In Jesus’ case, he was crucified alone.

- The Gospels note his disciples had fled, and only a handful of women and “the disciple whom he loved” stood by.

- With one man to bury, and with Joseph of Arimathea’s intervention (a wealthy, respected figure), a same-day burial was both possible and consistent with Jewish law.

Key Insight: The combination of archaeological finds, Jewish law, and the fact that Jesus was crucified as a lone figure — not in a mass uprising — makes his burial historically credible.

10. Conclusion: The Unshakable Core

Even the most skeptical historians agree that certain facts about Jesus can be known with near certainty. These are not matters of faith, but of historical consensus:

- Jesus was a Galilean Jew who lived in the early first century.

- He had siblings, and his primary language was Aramaic.

- He was baptized by John the Baptist.

- He became a teacher of an apocalyptic worldview, proclaiming that God’s kingdom was at hand.

- He gathered disciples.

- He was handed over to the Roman authorities during the governorship of Pontius Pilate.

- He was crucified.

- He died by crucifixion.

- Afterward, his followers believed they saw him risen from the dead.

Bart Ehrman (agnostic scholar):

“One of the most certain facts of history is that Jesus was crucified on orders of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate.” (The New Testament: A Historical Introduction, 2011, p. 163).

Gerd Lüdemann (atheist scholar):

“It may be taken as historically certain that Peter and the disciples had experiences after Jesus’ death in which he appeared to them as the risen Christ.” (The Resurrection of Jesus, 1994, p. 38).

Why This Matters

- Unity across Christian traditions.

Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant Christians may differ in many areas, but all agree on these essentials. The death and resurrection of Jesus are the shared foundation of the faith. This is enough to unite Christians across traditions. - Engagement with the unaffiliated and skeptical.

Even using only atheist consensus, we have enough to demonstrate that Christianity is rooted in real history. Jesus was crucified under Pilate, and his followers truly believed they saw him alive again. This gives us a credible basis for dialogue with the unaffiliated, agnostics, and atheists.

Key Insight: The earliest Christians did not persuade the world with abstract arguments, but with the visible impact of their faith on their communities. They cared for the poor, rescued abandoned children, tended the sick, and loved one another as family. The greatest apologetic was not simply what they believed about Jesus, but how those beliefs changed their lives.

And the same is true today. The unshakable core — Jesus crucified, buried, risen, and exalted — continues to change lives and communities. It is enough for our faith, enough for Christian unity, and enough to show the world that this faith is historically reliable and still alive.

Discover more from Living the Bible

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.