In AD 212, Emperor Caracalla issued the most sweeping reform in Roman history. Through the Constitutio Antoniniana, he declared that every free inhabitant of the empire was now a citizen of Rome. From Britain to Arabia, from Spain to Syria, millions were bound under one law.

The jurist Ulpian preserves the decree:

“All those throughout the Roman world who are at present Roman subjects shall be given Roman citizenship.” (Digest 1.5.17)

Caracalla wanted to be remembered as the man who united the world. But senator Cassius Dio unmasks his motive:

“He did this not so much to honor them as to increase his revenues, for he levied new taxes on all citizens.” (Roman History 78.9, Loeb)

Rome’s citizenship was about money and bureaucracy. Christians, however, were already proclaiming another citizenship — one written in heaven.

1. Our Citizenship Is in Heaven

The apostle Paul had written it centuries earlier:

“But our citizenship (politeuma) is in heaven, and from it we await a Savior, the Lord Jesus Christ.” (Philippians 3:20)

The anonymous Epistle to Diognetus (late 2nd or early 3rd century) echoed Paul:

“They live in their own countries, but only as aliens; they take part in everything as citizens, and endure everything as foreigners. Every foreign land is their homeland, and every homeland is foreign. They dwell on earth, but their citizenship is in heaven.” (Diognetus 5.5)

Tertullian of Carthage (c. 160–225) ridiculed Rome’s pride:

“We are but of yesterday, and we have filled your cities, your islands, your forts, your towns, your assemblies, your very camp, your tribes, your decuries, the palace, the senate, the forum. We have left you nothing but your temples.” (To Scapula 2, Loeb)

And he pressed the contrast further:

“We acknowledge one commonwealth, the whole world. We renounce your spectacles, we refuse your festivals, we shrink from your public banquets; yet we share with you the benefits of your commerce, your markets, your baths, your workshops, your inns, your fairs, and all the other arrangements of your ordinary life. We sail with you, we fight with you, we till the ground with you, and we trade with you. We are as much your fellow-citizens as we are fellow-men; only we differ from you in that we do not worship your gods.” (Apology 42)

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185–254) gave the same answer when pagans accused Christians of neglecting civic duty:

“If you want to see the real commonwealth of God, you will find it in those who live according to the law of God. This is the heavenly city, not made by men but by God.” (Contra Celsum 8.75)

And Minucius Felix records both the sneer and the reply of Christians:

Pagan critic: “They recognize one another by secret marks and signs; they love one another almost before they know one another. They call themselves brothers and sisters indiscriminately.” (Octavius 9)

Christian reply: “Yes, we are called brothers — as children of one God, united in the bond of one faith, of one hope, of one spirit.” (Octavius 31)

Rome created citizens. Christ created a family.

2. Citizenship Without Safety

Caracalla’s decree offered no protection from tyranny. In AD 215, after Alexandrian plays mocked him, he unleashed slaughter in the city.

Dio reports:

“He slaughtered many of the people, not only those of the council and the leaders, but also a great number of the populace.” (Roman History 78.23, Loeb)

Herodian echoes:

“He invited the leading citizens to a banquet, then slaughtered them with a multitude of others.” (History of the Empire 4.9, Loeb)

Citizenship could not save them. For Christians, this proved what Hippolytus of Rome was already teaching:

“The world hates the righteous, and persecution will never cease until the coming of the Lord.” (Refutation of All Heresies 9.7)

Rome could grant citizenship, but it could not grant safety.

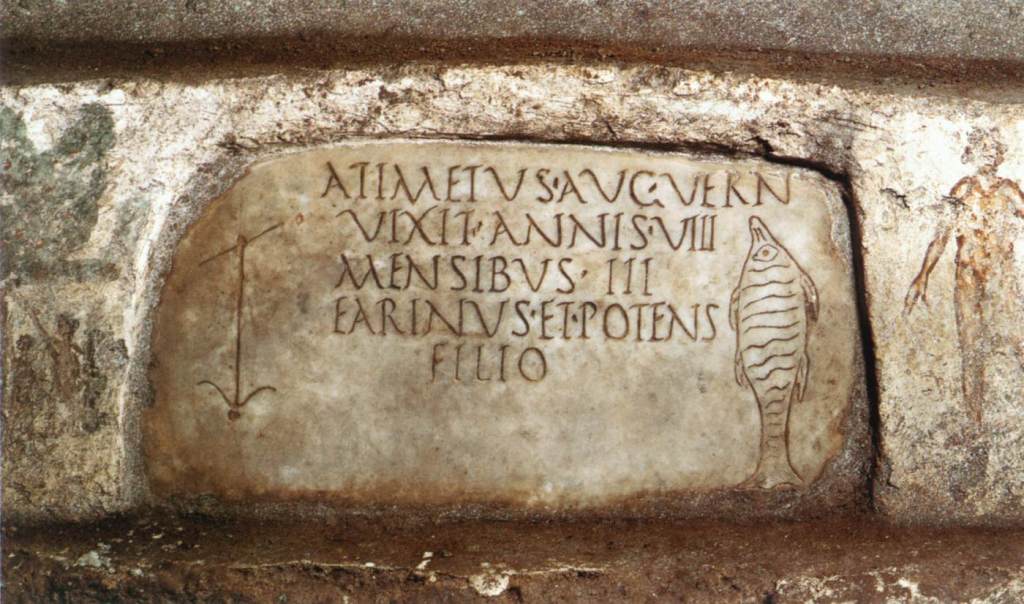

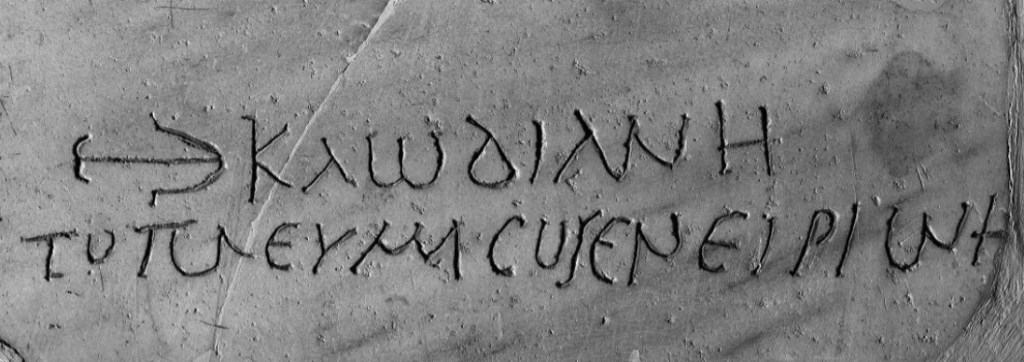

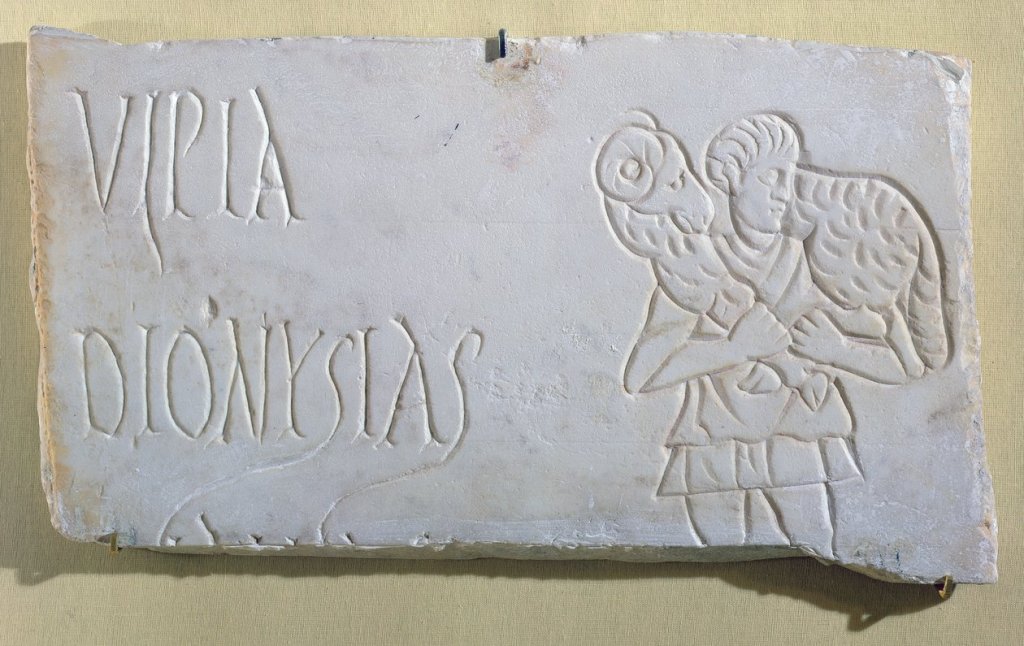

3. Symbols of a Different City (Archaeology and Inscriptions)

Caracalla inscribed citizenship into law. Christians inscribed theirs into stone, paint, and epitaphs.

The Fish (Ichthys)

- Clement of Alexandria (Paedagogus 3.11, c. 200): “And let our seals be either a dove, or a fish, or a ship scudding before the wind, or a musical lyre, which Polycrates used, or a ship’s anchor…”

- Tertullian (On Baptism 1, c. 200): “We little fishes, after the example of our Ichthys, Jesus Christ, are born in water.”

- Epitaph of Abercius (c. 180): “Faith everywhere led the way and set before me for food a fish from a fountain, a great one, pure, which a holy virgin drew up with her hands; and this Faith ever gave to friends to eat, having good wine, and giving it mixed with bread.“

This symbol carried a creed in five letters: ΙΧΘΥΣ — Jesus Christ, Son of God, Savior.

The Anchor of Hope

- Hebrews 6:19: “We have this hope as an anchor for the soul.”

It proclaimed that Christian security lay not in Rome but in Christ’s promises.

The Good Shepherd

- John 10:11: “The good shepherd lays down his life for the sheep.”

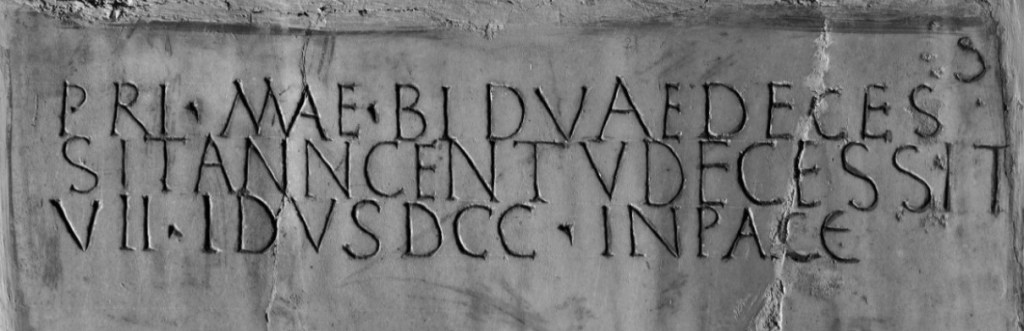

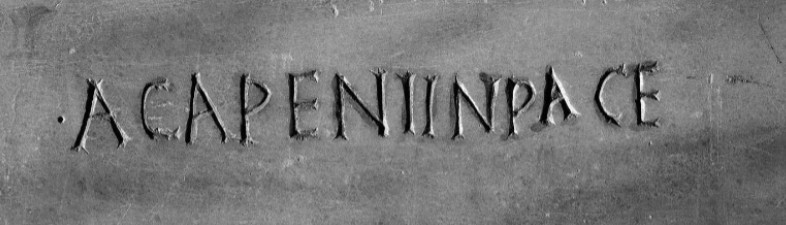

“In Peace” Epitaphs

Instead of titles and achievements, Christians emphasized peace and family:

- “Marius, a faithful brother, lies in peace.”

- “Victorina, in Christ, in peace.”

- “Aurelius, our brother, sleeps in peace.”

These short lines proclaimed hope beyond death.

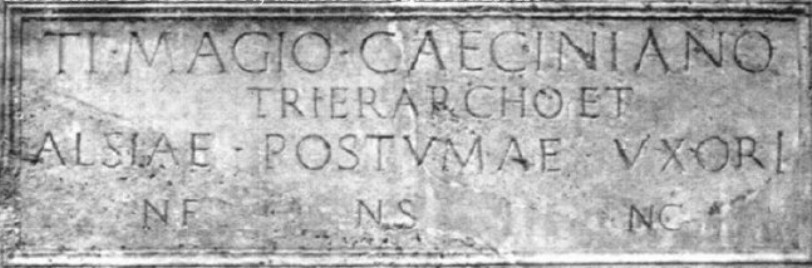

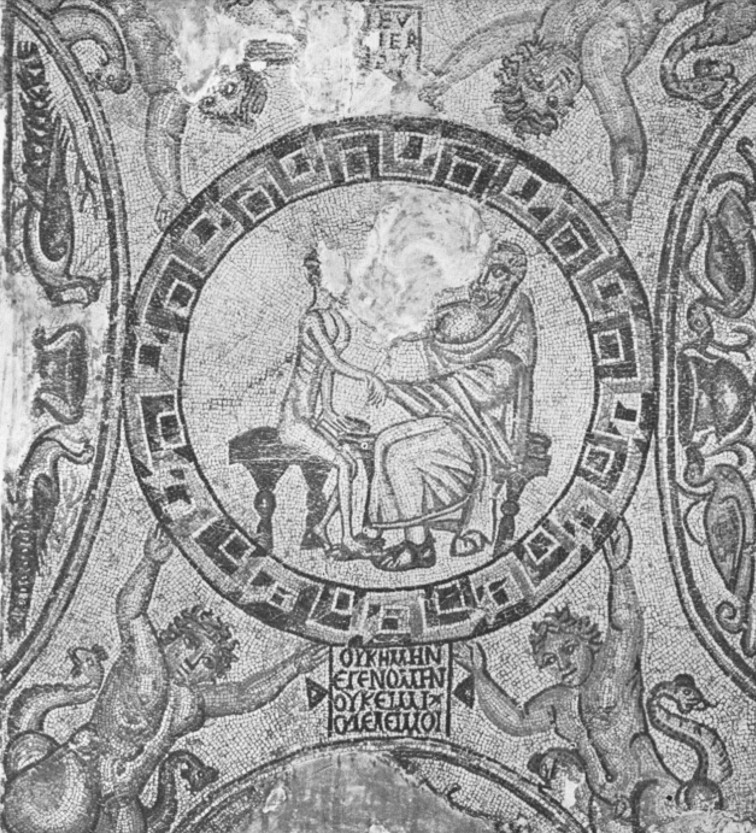

Pagan Contrast: NFFNSNC

Meanwhile, the most common pagan epitaph read:

NFFNSNC = Non fui, fui, non sum, non curo.

“I was not; I was; I am not; I do not care.”

This fatalistic phrase covered tombs across the empire in both Latin and Greek versions. It was a resignation to nothingness after death, just like nothingness before birth.

The difference is stark:

- Pagan stones: “I am not; I do not care.”

- Christian stones: “In peace, in Christ.”

Caracalla’s law gave paper citizenship. But death revealed its emptiness. Christian epitaphs declared a better citizenship, one that promised peace and belonging beyond the grave.

4. Beyond the Catacombs: Heavenly Citizenship in Daily Life

Christian symbols spread far beyond the catacombs:

- Megiddo Mosaic (c. 230): a church floor dedicated to “The God Jesus Christ.”

- Dura-Europos House-Church (AD 232–233): with frescoes of the Good Shepherd, Jesus healing, and the empty tomb.

- Personal items: rings with anchors, gems with fish, oil lamps with doves.

- Graffiti: scratched fish and creeds in plaster walls.

Citizenship of heaven was not abstract. It was carried on rings, stamped on lamps, carved in mosaics, and painted on walls.

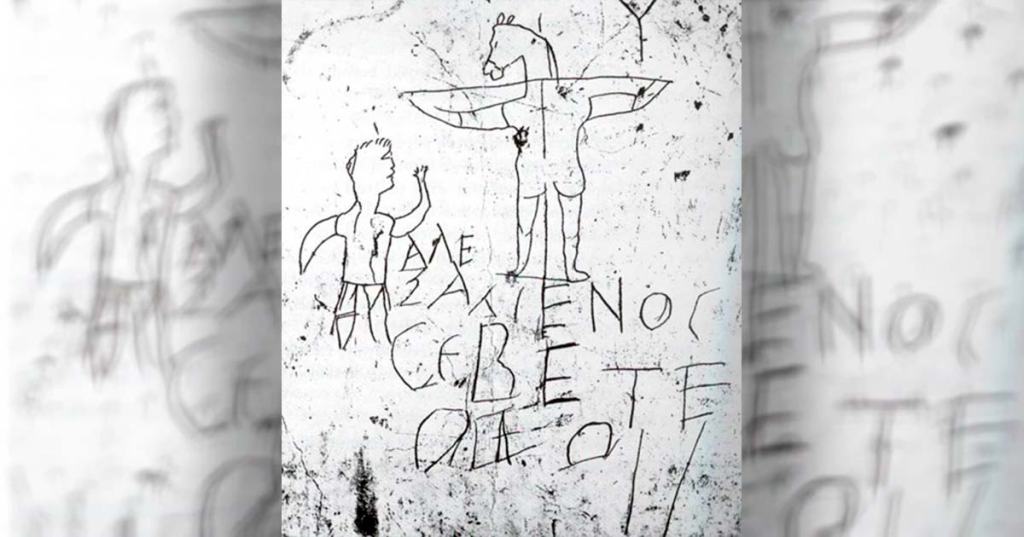

5. Why Not the Cross?

Strikingly, the cross itself was absent from Christian art in this period. Crucifixion was still a brutal Roman punishment, too shameful to display proudly.

Pagans mocked it — as in the Alexamenos graffito (late 2nd c.), where a donkey-headed figure is crucified with the caption: “Alexamenos worships his god.”

Christians confessed the cross in veiled ways:

- The staurogram (⳨) in early manuscripts like P66 and P75.

- Anchors drawn to echo a cross shape.

Only after Constantine outlawed crucifixion (c. 315) did Christians adopt the cross openly as their emblem.

6. Macrinus: A Passing Shadow

Caracalla was murdered in AD 217. His successor, Macrinus, reigned only a year before being overthrown. He left no policy toward Christians. His brief rule reminds us: emperors come and go. The church endures.

Conclusion: The True Citizenship

Caracalla claimed to unite the empire by decree. But Christians in his day already lived in a higher unity.

- Paul: “Our citizenship is in heaven.” (Philippians 3:20)

- Diognetus: “They dwell on earth, but their citizenship is in heaven.”

- Tertullian: Christians filled the empire yet belonged to one greater commonwealth.

- Origen: The real commonwealth is the heavenly city made by God.

- Minucius Felix: Christians are brothers and sisters, bound in one hope.

- Hippolytus: Persecution will never cease until Christ returns.

- Archaeology: fish, anchors, shepherds, mosaics, inscriptions, and epitaphs marked their heavenly belonging.

- Pagan epitaphs: resignation to nothingness.

- Christian epitaphs: peace in Christ.

Rome’s citizenship was a tax roll. Christian citizenship was a family.

Rome’s citizenship could be revoked in blood. Christian citizenship promised peace beyond death.

Caracalla and Macrinus are remembered as violent and forgettable. The Christians of their day are remembered for confessing: “Our citizenship is in heaven.” (Philippians 3:20)