This script traces how the Gospels and Acts moved from eyewitness proclamation to the Greek literary works we have today. We look at modern views of Scripture, the rise of inerrancy, the early church’s rule of faith, Origen’s view of the Bible, the anonymity of the earliest manuscripts, and how ancient books were written through dictation and scribal collaboration. We then show why the Gospels fit perfectly into that world and why their central message — the death and resurrection of Jesus, witnessed by many — remains consistent from Paul’s earliest letters all the way through the second century. Finally, we address the claim that Jesus is just another myth and explain why the earliest Christian testimony belongs in a completely different category.

SECTION 1 — How Christians View Scripture Today

Overview

Major survey organizations such as Gallup, Barna/ABS, and Pew consistently report that the strict “word-for-word literal” or “error-free in every detail” view of Scripture represents a minority position among Christians today.

I. Gallup Poll (2022)

Gallup’s most recent national data show:

Only 20 percent of American adults say “the Bible is the actual word of God and is to be taken literally, word for word.”

— Gallup, 2022

Among Christians, that rises only to 25 percent.

A majority—58 percent—say the Bible is inspired by God but

“…not everything in it should be taken literally.”

II. American Bible Society / Barna Group — State of the Bible (2021)

Barna/ABS data further show:

- 26 percent believe the Bible is “the actual word of God and should be taken literally.”

- 29 percent believe the Bible is the word of God and without error, though parts may be symbolic.

- 55 percent of U.S. adults hold what the survey calls a “high view of Scripture,” a broad category that does not require strict inerrancy.

Source: State of the Bible 2021.

III. Pew Research Center (2017)

Among Christians in the United States:

- 39 percent say the Bible is the word of God and should be taken literally, word for word.

- 36 percent say the Bible is the word of God but should not be taken literally.

Source: Pew Research Center, 2017.

IV. Combined Analysis and Key Conclusions

Across all three major data sets:

- The strict literalist or strict inerrant view appears consistently in the 20–30 percent range among Christians.

- A larger group, typically 40–60 percent, views Scripture as inspired and authoritative but not strictly literal and not perfect in every technical detail.

- The remaining share hold alternative views (e.g., inspired but not unique, ancient wisdom, not inspired).

Key Insight for Historical Study

Strict inerrancy is not the global or majority Christian position.

The majority of Christians today read Scripture as inspired without assuming complete literal precision.

SECTION 2 — When and Why the Doctrine of Inerrancy Developed

I. Overview

The modern doctrine of biblical inerrancy—the belief that Scripture is absolutely without error in every detail, including matters of history, science, chronology, and geography—is not an ancient Christian doctrine.

It does not appear:

- in the early Church,

- in the writings of the Church Fathers,

- in medieval theology,

- or even in the Protestant Reformation.

It arose late in Christian history, in response to developments in the Enlightenment and the rise of historical-critical scholarship during the 1700s–1800s.

This section describes that development factually and systematically.

II. The Rise of Historical-Critical Scholarship (18th–19th Centuries)

Beginning in the late 1700s, European scholars began studying the Bible the way they studied all other ancient literature.

This involved:

- comparing manuscripts,

- examining internal contradictions,

- studying literary sources and editorial layers,

- questioning traditional views on authorship,

- analyzing historical claims.

Major figures in this intellectual shift include:

- Johann Salomo Semler (1725–1791) — developed early concepts of canon criticism

- Gotthold Ephraim Lessing (1729–1781) — raised questions about the “ugly ditch” between history and faith

- Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) — encouraged historical methods in theology

- F. C. Baur (1792–1860) and the Tübingen School — interpreted the New Testament through Hegelian historical development

Baur’s work was especially influential.

He argued that:

- the early church contained competing theological factions (“Petrine” vs. “Pauline”),

- some New Testament books were pseudonymous,

- Acts was a harmonizing narrative,

- and the Gospels reflected theological interpretation rather than raw historical memory.

This was the most sustained academic challenge to traditional Christian assumptions in 1,700 years.

III. The “Seven Undisputed Letters of Paul” — A Major Scholarly Gain

While the rise of historical criticism challenged traditional views, it also produced one of the most important positive contributions to modern Christian historical study:

the identification of Paul’s seven undisputed letters.

Across the entire scholarly spectrum—conservative, moderate, liberal, Jewish, atheist—there is near-unanimous agreement that the following letters are authentic, first-person writings of Paul, composed in the 50s AD:

- Romans

- 1 Corinthians

- 2 Corinthians

- Galatians

- Philippians

- 1 Thessalonians

- Philemon

Their significance:

- They are the earliest Christian documents we possess.

- They were written within 20–25 years of Jesus’ death.

- They reflect the beliefs of the first generation of Christians.

- They give direct access to how the earliest churches functioned.

- They anchor Christian history in verifiable first-person testimony.

This is one of the strongest historical foundations Christianity possesses.

It comes directly out of the same academic movement that challenged traditional assumptions.

IV. The Princeton Response — Birth of Modern Inerrancy (Late 1800s)

In the late 19th century, conservative Protestant theologians in America formulated a new doctrine designed to defend Scripture against the challenges of historical criticism.

This movement centered at Princeton Theological Seminary with:

- Charles Hodge (1797–1878)

- B. B. Warfield (1851–1921)

They argued:

- Scripture is inspired by God.

- God cannot err.

- Therefore Scripture must be without error in everything it affirms.

This produced—for the first time in Christian history—a formal doctrine of verbal plenary inerrancy.

This formulation differs from earlier Christian attitudes in several ways:

- Early Christians accepted non-literal readings and apparent contradictions (e.g., Origen).

- Medieval theologians focused on spiritual senses, not literal precision.

- Reformers emphasized authority and clarity, not inerrancy in scientific or historical detail.

The Princeton formulation represented a new doctrinal development, driven by the desire to provide a clear defense of Scripture in an age of modern criticism.

V. Spread and Codification of Inerrancy (1900s)

The Fundamentals (1910–1915)

A series of booklets published between 1910 and 1915 that defined “fundamental doctrines.”

One of the central doctrines was:

- Biblical inerrancy.

This launched the American fundamentalist movement.

Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy (1978)

Written by over 200 evangelical leaders, defining inerrancy as:

“Scripture is without error or fault in all its teaching.”

This document became the standard articulation of inerrancy in evangelical seminaries and churches.

VI. Combined Historical Analysis

- The ancient Church did not define Scripture as inerrant in the modern, technical sense.

- Medieval and Reformation theology did not articulate verbal plenary inerrancy.

- Modern inerrancy developed in the late 1800s as a response to the intellectual challenges of the Enlightenment and historical criticism.

- Meanwhile, critical scholarship also produced the seven undisputed letters of Paul, which remain some of the earliest and most historically secure Christian documents.

This historical framing allows for honest examination of the composition of the Gospels and Acts without assuming modern categories that did not exist in the early Church.

SECTION 3 — The Ancient Rule of Faith, Origen’s View of Scripture, and Internal Evidence from the Gospels and Acts

I. The Ancient Rule of Faith

Early Christians summarized their core beliefs in a short confession known as the rule of faith (regula fidei).

While only some writers explicitly use the phrase, the content of the rule of faith appears consistently across all major early Christian sources of the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd centuries — including the New Testament, the Apostolic Fathers, early apologists, and even in anti-christian works.

Core elements of the ancient rule of faith:

- Belief in one God, the Father, the Creator and Sovereign

- Belief in Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who became flesh, was crucified, died, was buried, rose, and ascended

- Belief in the Holy Spirit, who indwells believers and produces righteous living

- Belief in final judgment, in which Christ judges the living and the dead

The rule of faith does not include:

- inerrancy

- doctrines of textual perfection

- literalism

- attempts to harmonize every Gospel detail

- modern demands of historical precision

Early Christian faith celebrated inspiration, but inspiration was not equated with technical inerrancy or literal exactitude.

II. Origen (c. AD 185–253): Background and Significance

Origen of Alexandria (later Caesarea):

- produced the first systematic Christian theology (De Principiis),

- created the Hexapla, an enormous comparative edition of the Old Testament,

- and wrote extensive commentaries, including the earliest surviving major commentary on a Gospel (the Commentary on John).

Origen provides the earliest comprehensive Christian doctrine of Scripture, showing how early Christians understood Scripture’s complexity, its non-literal elements, and its theological depth. The important takeaway from Origen is that he readily recognized contradictions and historical inaccuracies in the biblical documents. We don’t need to necessarily take on his solution to them but to understand that a Christian can readily admit them.

III. Origen’s View of Scripture — De Principiis, Book IV

1. Scripture contains literal history AND non-literal elements

“The Scriptures were written by the Spirit of God, and because they are divine they contain within them a meaning which escapes the casual reader.

Many things that are literally true are inserted for the edification of those unable to see beyond the letter.

But others — indeed very many — are written so that they cannot possibly have happened as they are described, nor be literally true, yet they contain deep mysteries.”

— De Principiis IV.1.6

2. The Spirit intentionally inserted “stumbling-blocks”

“The Word of God has purposely inserted certain things which appear impossible, absurd, or contradictory, that we may be driven to search for a meaning worthy of God.

For the simple are edified by what is written, but those who have advanced may be exercised by the stumbling-blocks in the text.”

— De Principiis IV.2.9

“If everything in Scripture were plain history, we should not believe it to be inspired by God;

but now, by means of these apparent inconsistencies, the Spirit calls us to the hidden sense.”

— De Principiis IV.2.9

3. Apparent Gospel discrepancies are theologically purposeful

“If, when we read the Gospels, we find things which cannot both be true in the letter — if the same event is said to have happened differently or in a different order —

let us not charge the writers with error, but seek the deeper intention of the Spirit.

For these very differences lead us from the bodily sense to the soul of Scripture.”

— De Principiis IV.3.5

“He who insists that all the details must literally agree is like one who insists that Christ’s words are only human and not divine.”

— De Principiis IV.3.5

4. The threefold sense of Scripture

“The bodily sense is the outward narrative.

The psychic sense teaches moral conduct.

The spiritual sense reveals Christ the Logos and the heavenly realities.

Wherever in Scripture the narrative appears impossible or irrational, the Holy Spirit warns us not to remain at the letter but to seek the truth hidden beneath.”

— De Principiis IV.2.4–5

5. Scripture as spiritual training

“The divine Word has adapted Himself to our weakness as a wise physician, mixing truth with difficulty so that we may be both nourished and tested.

The simple find milk; the mature are compelled to search for solid food.

Thus Scripture is a training ground for the soul, not merely a record of history.”

— De Principiis IV.2.8

6. Apparent contradictions are deliberate divine design

“If one observes with care, he will find many things in Scripture which appear to be at variance.

But this very difficulty shows that the divine wisdom has so arranged them to prevent the unworthy from understanding, and to urge the worthy to seek the hidden harmony.”

— De Principiis IV.2.9

IV. Origen’s Commentary on John (Book X)

Origen applies his interpretive method directly to the Gospel narratives while recognizing their historical inaccuracies and contradictions.

1. Non-literal events with spiritual truth

“In the Scriptures many things are written which did not actually happen, and yet spiritually they happened.

The deeper truth is discerned only by one who has the mind of Christ.”

— Commentary on John X.4

2. Purposeful “interruptions of history”

“The Word of God arranged the Scriptures with wisdom, placing certain stumbling-blocks and interruptions of history,

that we might not be drawn to the letter but be summoned to the Spirit.”

— Commentary on John X.18

3. Literalism yields absurdity

“If we dwell upon the letter and follow the narrative as mere history, absurdities will necessarily result —

impossible statements will be present.

But if we seek the spiritual meaning, these things will be found to be beautiful and divine.”

— Commentary on John X.20

4. Inconsistency is not error

“Where the narrative appears inconsistent, we must not suppose the Spirit of God to be at fault;

rather we must ask what deeper meaning the Spirit intends us to seek.”

— Commentary on John X.21

SECTION 4 — The Gospels and Acts: From Anonymity to Authorship

I. Early Gospel and Acts Manuscripts Are Anonymous

The earliest surviving manuscripts of the Gospels and Acts are anonymous.

No author names appear in the original text of any early papyrus.

Key early papyri:

- P52 — fragment of John 18, dated c. AD 125–150

- P45 — fragments of all four Gospels + Acts, dated c. AD 200–250

- P66 — large portion of John, dated c. AD 175–200

These manuscripts contain only the narrative text.

They do not include titles such as:

- “The Gospel according to Matthew”

- “The Gospel according to Mark”

- “The Gospel according to Luke”

- “The Gospel according to John”

The familiar title headings (Κατὰ Ματθαῖον, Κατὰ Μᾶρκον, Κατὰ Λουκᾶν, Κατὰ Ἰωάννην) were added later by scribes during the process of copying and circulating the texts.

Thus, the earliest physical evidence confirms that the Gospels and Acts were originally anonymous documents.

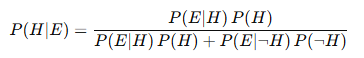

II. Internal Evidence from the Gospels and Acts

1. Matthew (Matthew 9:9)

Matthew’s calling:

“As Jesus passed on from there, he saw a man called Matthew sitting at the tax booth; and he said to him, ‘Follow me.’ And he rose and followed him.”

- Third-person narration

- No autobiographical detail

- Based on Mark 2:13–17 (where the name is Levi)

→ Indicates literary dependence, not personal recollection.

2. John (John 21:24)

Final editorial voice:

“This is the disciple who is bearing witness to these things, and we know that his testimony is true.”

→ Indicates multiple hands involved — a community affirming the witness, not a lone author.

3. Luke–Acts (Luke 1:1–4; Acts 1:1–2)

Luke’s prologue:

“Many have undertaken to compile a narrative…

just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses…

it seemed good to me also… to write an orderly account…

for you, most excellent Theophilus…”

- Luke is a compiler, not an eyewitness

- Used written sources

- Employed investigation

- Wrote under patronage

Acts 1:1–2 confirms Luke wrote both volumes.

4. Mark

Mark contains no internal claim of authorship.

It begins abruptly and presents no first-person markers.

5. Summary of Internal Literary Evidence

Across all four Gospels and Acts:

- All are anonymous in their original text.

- None claims to be written by an apostle.

- Luke explicitly describes a research-based, source-dependent, patron-funded project.

- John reflects community authorship.

- Matthew depends on earlier written sources.

- Mark presents no authorial claim.

This internal evidence aligns with the historical realities of ancient literary production and the external evidence described in later sections.

III. Early Christian Writers Treat the Gospels as Anonymous (AD 95–180)

For approximately eighty-five years after the composition of the Gospels, Christian authors quote or use Gospel material without naming Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John.

Early Christian Writers (AD 95–180) Who Use the Gospels Anonymously

| Writer | Approx. Date | How They Use Gospel Material | Do They Name Matthew, Mark, Luke, John? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Clement (Rome) | c. AD 95 | Quotes Jesus’ teachings | No |

| Ignatius of Antioch | c. AD 110 | Echoes Matthew and Luke | No |

| The Didache | c. AD 100–120 | Parallels Sermon on the Mount | No |

| Polycarp of Smyrna | c. AD 110–135 | Quotes Matthew, Luke, Acts | No |

| Quadratus (Apologist) | c. AD 125 | Mentions living eyewitnesses | No |

| Aristides of Athens | c. AD 125–138 | Summarizes Jesus’ life and teaching | No |

| Marcion of Pontus | c. AD 140–150 | Uses shortened form of Luke’s Gospel | No — never calls it “Luke” |

| Justin Martyr | c. AD 150 | Calls them “Memoirs of the Apostles” | No |

| Tatian of Assyria | c. AD 170 | Produces Diatessaron (four-Gospel harmony) | No |

| Athenagoras of Athens | c. AD 177 | Uses Gospel traditions | No |

| Theophilus of Antioch | c. AD 180 | Quotes John 1:1 | No |

Summary of this pattern

Across Rome, Syria, Asia Minor, and Athens — and across genres (letters, apologies, summaries, harmonies) — Christian writers:

- quote the Gospels,

- depend on them,

- appeal to them,

- arrange them,

- and harmonize them,

…but never attach the names Matthew, Mark, Luke, or John.

In the first 85 years of Christian writing, the Gospels functioned as anonymous authoritative narratives.

IV. The First Surviving Attributions: Papias of Hierapolis (AD 110–130)

Papias is the earliest figure to associate specific authors with Gospel material.

His work survives only in quotations preserved by Eusebius (4th century), and his information is not firsthand.

Papias explicitly attributes his knowledge to someone he calls “the Elder”, whose identity is unknown.

“The Elder said this:

Mark, having become Peter’s interpreter, wrote down accurately whatever he remembered—though not in order—for he had not heard the Lord nor followed Him,

but afterwards followed Peter, who used to give teaching as necessity demanded,

not making an ordered arrangement of the Lord’s sayings.Therefore Mark did nothing wrong in writing down some things as he remembered them,

for he took care not to omit anything he had heard or to falsify anything in them.”

And on Matthew:

“Matthew compiled the logia in the Hebrew language,

and each interpreted them as he could.” (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 3.39.15–16)

Key historical observations:

- Papias’ statements rely entirely on “the Elder”, an unidentified figure.

- Papias does not claim personal acquaintance with any apostle.

- He discusses only Mark and Matthew, not Luke or John.

- He acknowledges Mark’s account is not in chronological order.

- He says Matthew wrote logia (“sayings”) in Hebrew, requiring later translation.

Papias provides partial, indirect, and secondhand authorial attributions.

V. The Muratorian Fragment (c. AD 170, Probably Rome)

The Muratorian Fragment, the earliest surviving list of New Testament books, dates to c. AD 170 and was likely composed in Rome.

“The third book of the Gospel is that according to Luke.

Luke, the well-known physician… composed it in his own name according to Paul’s thinking.The fourth of the Gospels is that of John, one of the disciples…” Excerpt (Metzger translation)

The beginning is damaged but almost certainly mentioned Matthew and Mark.

This is the first surviving document to name Luke and John explicitly as Gospel authors.

VI. Irenaeus of Lyons (c. AD 180)

In Against Heresies 3.1.1, Irenaeus gives the earliest complete fourfold authorship tradition:

“Matthew among the Hebrews issued a written Gospel…

Mark, the interpreter of Peter, handed down in writing what Peter preached.

Luke, the companion of Paul, recorded the Gospel preached by him.

John, the disciple of the Lord, published his Gospel while living in Ephesus.”

From Irenaeus onward, the fourfold authorship tradition becomes standard in the Christian movement.

VII. Why These Names Arise in the Late Second Century

The second century saw the emergence of numerous writings claiming apostolic authority:

- Gospel of Peter,

- Gospel of Thomas,

- Gospel of Mary,

- Gospel of the Egyptians,

- Acts of Paul and Thecla,

- multiple apocalypses.

To establish which texts preserved authentic apostolic teaching, church leaders anchored the four trusted Gospels to four authoritative figures.

The chosen pattern: two apostles + two apostolic companions

| Gospel | Connection Claimed | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Matthew | One of the Twelve | Eyewitness authority |

| John | One of the Twelve | Eyewitness authority |

| Mark | Linked to Peter | Peter’s interpreter |

| Luke | Linked to Paul | Paul’s companion |

This pairing reflects the early Church’s two central missionary pillars: Peter and Paul.

VIII. Historical Reconstruction

A historian synthesizing manuscript and literary evidence would conclude:

- The Gospels and Acts were originally anonymous.

- Early Christians used them anonymously for nearly a century.

- The first authorial attributions arise between AD 110–180.

- Papias provides partial, indirect information from an unknown Elder.

- The Muratorian Fragment names Luke and John.

- Irenaeus supplies the first full fourfold tradition.

- The chosen authors (two apostles, two companions) represented a balanced response to competing apocryphal and pseudonymous texts.

This remains the most historically probable explanation for the development of Gospel authorship traditions.

SECTION 5 — Literacy, Education, and How the Gospels Could Be Written in Greek

I. Historical Problem Statement

The Gospels are written in coherent, well-structured Greek prose—capable of quoting the Septuagint, arranging material thematically, shaping narratives, and using established literary techniques.

This raises a central historical question:

How could Aramaic-speaking Galilean laborers produce Greek literary works of this quality?

To answer this, we must examine:

- literacy in the Greco-Roman world

- literacy in Judea and Galilee

- the ancient system of dictation and secretaries

- scribal labor

- the earliest Christian written material

- and Luke’s own description of Gospel writing

II. Literacy in the Greco-Roman World

The standard reference is William V. Harris, Ancient Literacy (Harvard University Press, 1989).

Harris’s findings:

- Only 10–15% of the Roman Empire could read at all.

- Only 1–2% could write sustained prose.

- Literary composition required elite education in grammar and rhetoric.

- Writing was normally performed by professional scribes, not by authors.

- Producing a literary Greek work required:

- advanced schooling

- rhetorical training

- scribal assistance

- materials and time

III. How Educated Romans Actually Produced Literature

Even highly educated Romans rarely wrote with their own hands.

They composed through dictation to trained secretaries (amanuenses) who expanded, corrected, and produced written texts.

Pliny the Younger (AD 61–113)

“When I dictate while walking, my secretary writes beside me, and I note down in my tablets whatever comes to me. Later I revise and correct what he has taken down.”

— Epistles 3.5.10

“Often I dictate even in my carriage; the jolting of the road only sharpens my invention.”

— Epistles 9.36

Cicero (106–43 BC)

“I am sending you the copy just as my secretary took it down from my dictation.”

— Ad Fam. 16.21

“Tiro has written this for me; my eyes are tired, and I cannot write myself.”

— Ad Att. 13.25

Seneca (4 BC – AD 65)

“I dictate even while walking; my voice serves for my hand.”

— Epistle 83.2

Dictation was the standard method of literary composition.

IV. Literacy in Judea and Galilee

The standard reference is Catherine Hezser, Jewish Literacy in Roman Palestine (Mohr Siebeck, 2001)

Hezser’s findings:

Literacy in 1st-century Judea occurred in four levels:

1. Basic Reading Literacy

- Recognizing letters or simple words.

- Typically limited to trained synagogue readers.

2. Functional Writing Literacy

- Writing one’s name or simple marks.

- Does not imply the ability to write sentences or documents.

3. Document Literacy

- Ability to produce legal or commercial documents.

- In Roman Palestine these were produced by professional scribes, not by ordinary people.

4. Literary Writing Literacy

- Ability to compose extended Greek/Hebrew prose:

narratives, histories, letters, theological works. - Required years of elite education in grammar, rhetoric, and composition.

- Restricted to a very small elite:

- priests

- wealthy urban families

- administrators

- trained scribes

Hezser’s conclusions:

- Rural reading literacy: under 5%

- Rural writing literacy: even lower

- Literary writing ability: virtually nonexistent among Galilean laborers

- Writing was a professional trade, not a household skill

Acts 4:13 confirms Hezser’s findings

“Now when they saw the boldness of Peter and John, and perceived that they were unlettered and ordinary men, they were astonished.”

— Acts 4:13

Agrammatoi = lacking formal literary education.

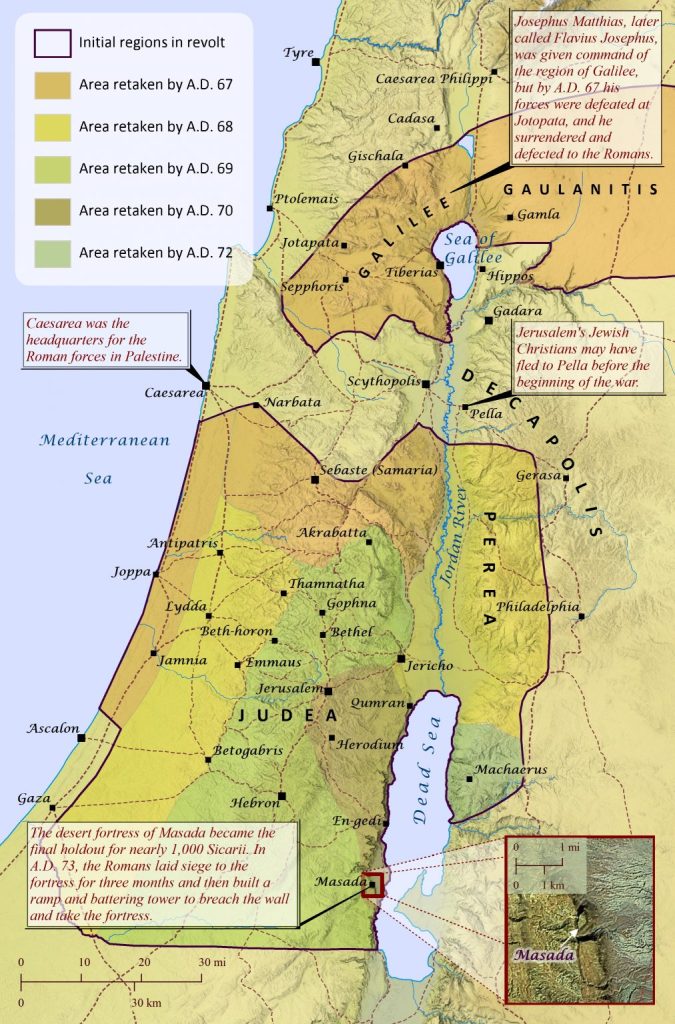

V. Only Two Palestinian Jews in the First Century Are Known to Have Written Greek Books

Only two Palestinian Jews from the 1st century produced Greek literary works:

1. Flavius Josephus (AD 37 – c.100)

Priestly aristocrat; author of Jewish War, Antiquities, Life, Against Apion.

2. Justus of Tiberias (late 1st century)

Galilean administrator; author of a Chronicle of the Jewish Kings.

Sources: Eusebius, HE 3.10; Photius, Bibliotheca 33.

This underscores how rare Greek literary writing was among Palestinian Jews.

VI. How Ancient Romans Wrote Books and Letters

The New Testament was produced inside the same literary ecosystem described by six major secular scholars, none of whom write from a religious or apologetic standpoint.

1. William A. Johnson — Duke University

Field: Classics, papyrology

Key Work: Readers and Reading Culture in the High Roman Empire (Oxford, 2010)

Johnson’s findings:

- Authors dictated.

- Secretaries expanded speech into polished prose.

- Scribes prepared fair copies.

- Literary slaves corrected grammar.

- Archives managed manuscripts.

- Authorship = authority over content, not handwriting.

2. A. N. Sherwin-White — Oxford University

Field: Roman imperial history

Key Work: The Letters of Pliny (Oxford, 1966)

Sherwin-White’s findings:

- Pliny dictated nearly everything.

- Used multiple secretaries.

- Wrote only brief signatures “in my own hand.”

- Approved drafts produced by scribes.

3. Stanley K. Stowers — Brown University

Field: Greco-Roman religion and ancient letter-writing

Key Work: Letter Writing in Greco-Roman Antiquity (1986)

Stowers’ findings:

- Letters followed standard rhetorical forms.

- Secretaries shaped style and texture.

- Stylistic variation is expected with different scribes.

- Stylistic differences do not imply different authors.

4. Roger S. Bagnall — Columbia University / NYU ISAW

Field: Papyrology

Key Works: Reading Papyri, Writing Ancient History (1995); Everyday Writing (2011)

Bagnall’s findings:

- Literacy was very low.

- Writing was a professional trade.

- Even private letters were often dictated.

- Scribes controlled written production.

5. Harry Y. Gamble — University of Virginia

Field: Early Christian book culture

Key Work: Books and Readers in the Early Church (Yale, 1995)

Gamble’s findings:

- Early Christians used Roman scribal systems.

- NT writings followed the workflow:

dictation → draft → revision → fair copy → circulation - Manuscripts show multiple scribal layers.

6. E. G. Turner — University College London

Field: Greek papyrology

Key Work: Greek Manuscripts of the Ancient World (1987)

Turner’s findings:

- Manuscripts show correction and collaboration.

- Literary works involved teams:

- dictating author

- shorthand secretary

- literary scribe

- corrector

VII. The New Testament’s Own Evidence for Secretaries

Romans 16:22

“I, Tertius, who wrote this letter, greet you in the Lord.”

Galatians 6:11

“See what large letters I am writing to you with my own hand.”

1 Corinthians 16:21

“I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand.”

Colossians 4:18

“I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. Remember my chains. Grace be with you.”

2 Thessalonians 3:17

“I, Paul, write this greeting with my own hand. This is the sign of genuineness in every letter of mine; this is the way I write.”

1 Peter 5:12

“Through Silvanus, a faithful brother as I regard him, I have written briefly to you, exhorting and declaring that this is the true grace of God.”

John 21:24

“This is the disciple who is bearing witness to these things, and we know that his testimony is true.”

These passages reveal:

- dictation,

- secretaries,

- final signatures,

- and collaborative authorship.

VIII. Most Probable Historical Model for Gospel Composition

1. Eyewitness proclamation

Apostolic preaching in Aramaic.

2. Translation and early written forms

As Christianity spread, its teachings were rendered into Greek in short written forms:

- sayings collections

- narrative summaries

- early creeds and hymns (1 Cor 15:3–5; Phil 2:6–11; Rom 1:3–4)

3. Literary composition by educated Greek-speaking Christians

Skilled writers shaped these into the four Gospels.

4. Secretarial and scribal collaboration

Secretaries shaped language; scribes produced copies; correctors refined grammar.

5. Patronage

Producing a Gospel required time, resources, and scribal labor.

Luke names his patron: “most excellent Theophilus.”

6. Final Gospels as collaborative literary products

The Gospels represent apostolic testimony, not apostolic penmanship.

IX. Internal Confirmation from Luke’s Prologue

Luke 1:1–4 confirms the entire model above:

“Many have undertaken to compile a narrative…

just as those who were eyewitnesses delivered them to us.

It seemed good to me also, having traced everything carefully,

to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus.”

Luke confirms:

- earlier written accounts

- eyewitness memory

- investigation

- orderly literary arrangement

- patronage

Luke 1:1–4 is the clearest ancient statement of how Gospel-writing actually worked.

SECTION 6 — “True Myth,” Pagan Parallels, and the Uniqueness of the Gospels

I. The Conversation That Changed C. S. Lewis’s Life

Before examining ancient claims about dying-and-rising gods, it is helpful to begin with one of the most important intellectual conversions of the 20th century — the conversion of C. S. Lewis, a long-time atheist, literary scholar, and expert in ancient myth.

Lewis was not persuaded by sermons or emotional appeals.

He was convinced by history, reason, and the nature of myth — especially through the influence of his close friend:

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

- Devout Roman Catholic

- Philologist at Oxford

- Scholar of ancient languages, Norse and Germanic myth, and medieval literature

- Later author of The Lord of the Rings

On the night of September 19–20, 1931, Lewis, Tolkien, and Hugo Dyson walked and talked for hours along Addison’s Walk at Magdalen College.

Lewis argued that Christianity carried the shape of myth and therefore could not be historically true.

Tolkien answered by explaining the nature of myth from a Catholic and philological perspective.

The key idea, expressed later in Tolkien’s own writings, is:

“We have come from God, and inevitably the myths woven by us, though they contain error,

will also reflect a splintered fragment of the true light, the eternal truth that is with God.”

— J. R. R. Tolkien, Letter 131 (to Milton Waldman)

All human myths — the dying gods, the heroic sacrifices, the returning kings — contain glimpses or refractions of divine truth, because human imagination itself reflects the image of God.

Lewis later reflected that Tolkien told him:

“The story of Christ is simply a true myth… the myth that really happened.”

— C. S. Lewis, Letter to Arthur Greeves, Oct. 18, 1931

This became the hinge of Lewis’s conversion.

II. Lewis’s Own Testimony About That Night

Two weeks after that conversation, Lewis wrote to his closest friend, Arthur Greeves:

“I have just passed on from believing in God to definitely believing in Christ — in Christianity.

My long night talk with Dyson and Tolkien had a great deal to do with it.

I have just discovered that the story of Christ is simply a true myth:

a myth working on us in the same way as the others,

but with this tremendous difference —

that it really happened.”

— C. S. Lewis, Letter to Arthur Greeves, October 18, 1931

This is Lewis — an Oxford scholar of myth — saying that Christianity is:

- myth-like in emotional and imaginative resonance,

- but historical in a way no pagan story ever claimed to be.

III. Lewis’s Mature Statement: “Myth Became Fact”

More than a decade later, Lewis articulated the same insight in its most famous form:

“The heart of Christianity is a myth which is also a fact.

By becoming fact it does not cease to be myth: that is the miracle.

Myth became fact.

It is the marriage of heaven and earth: Perfect Myth and Perfect Fact.”

— C. S. Lewis, “Myth Became Fact,” in God in the Dock (1944)

Lewis held that Christianity combines two realities:

- Mythic form — the universal human story-pattern of sacrifice, descent, rising, triumph

- Historical fact — real events in a real province under a real governor witnessed by real people

This led him to the conclusion that Christianity is unique, not one myth among many.

IV. Lewis on Myth and History Together

From Surprised by Joy:

“A myth is a story which conveys, in the world of imagination, a truth about the universe.

I did not know how to distinguish truth from myth

until I discovered that they could fit together,

that the true myth of Christianity gave meaning to all the others.”

— C. S. Lewis, Surprised by Joy

This quote bridges the gap between imagination and history:

- Pagan myths communicate something profound but symbolic.

- Christianity, Lewis realized, is the real event that the myths dimly echo.

V. Carrier’s Claim: Jesus as One More Dying and Rising God

Modern critics — especially Richard Carrier — argue that Jesus belongs among the ancient “dying and rising gods.”

They point to figures such as:

- Osiris

- Tammuz / Dumuzi

- Adonis

- Attis

- Dionysus

- Baal / Hadad

- Zalmoxis

- Inanna / Ishtar

- Romulus

- Asclepius

- Apollonius of Tyana

To evaluate the claim properly, we must examine:

- the earliest textual sources,

- the nature of each death,

- the nature of each “return,”

- the presence or absence of witnesses,

- the historical setting,

- and the genre of the stories.

This is what the comparison chart shows clearly.

VI. Comparison Chart — Carrier’s List vs. Jesus

| Figure | Earliest Source (Author & Date) | Eyewitness Claims? |

|---|---|---|

| Tammuz / Dumuzi | Sumerian laments & hymns (anonymous; c. 1800–1200 BC) | No |

| Adonis | Greek poetry — Hesiod fragments (7th c. BC); Ovid, Metamorphoses (1st c. BC–AD 1) | No |

| Attis | Catullus 63 (1st c. BC); Pausanias (2nd c. AD) | No |

| Osiris | Egyptian Pyramid Texts (c. 2400 BC); Plutarch, Isis and Osiris (1st c. AD) | No |

| Dionysus | Euripides, Bacchae (5th c. BC); later Orphic texts | No |

| Asclepius | Homeric Hymn (7th–6th c. BC); Pausanias (2nd c. AD) | No |

| Zalmoxis | Herodotus, Histories 4.94–96 (5th c. BC) | No |

| Inanna / Ishtar | Sumerian/Akkadian descent myths (2nd millennium BC) | No |

| Romulus | Livy, History of Rome 1.16 (late 1st c. BC); Plutarch, Romulus (early 2nd c. AD) | One visionary claim (Proculus) with multiple conflicting death stories |

| Apollonius of Tyana | Philostratus, Life of Apollonius (early 3rd c. AD) | One visionary claim with multiple conflicting death stories |

| Jesus of Nazareth | Paul’s letters (AD 50s); Synoptic Gospels (AD 65–90); John (AD 90–100) | Yes — multiple named witnesses, including groups |

VII. Why Lewis’s “True Myth” Insight Matters Here

Lewis provides the interpretive key modern readers lack:

The shape of the Christian story looks mythic — but its content is historical.

Pagan myths share the shape of death/descent/return:

but they lack:

- a date,

- a place,

- a known ruler,

- a legal trial,

- a specific execution method,

- a burial,

- named eyewitnesses,

- multiple early written accounts.

Lewis’s conclusion applies directly to the comparisons:

Christianity is not less than myth — it is myth that actually happened.

VIII. Summary of Section 6

- Carrier’s list involves mythic cycles, symbolic cult rites, and legendary stories without historical grounding.

- None feature bodily resurrection in real history witnessed by named individuals.

- The Gospels stand in a different category:

a historical claim inside a specific world with real rulers, places, dates, and witnesses. - C. S. Lewis — a scholar of myth — recognized Christianity’s uniqueness as Perfect Myth and Perfect Fact: mythic in resonance, historical in substance.

Conclusion

It is not a problem that the Gospels were originally anonymous. That was normal for ancient biography, and their names were attached later for practical and pastoral reasons. It is also not a problem that the Gospels sometimes differ from one another or contain historical tensions. Ancient writers did not write with modern precision, and early Christians like Origen openly acknowledged this. None of that undermines the central message the Gospels consistently proclaim.

Across all four Gospels and across Acts, the emphasis is clear and unified: Jesus died and was raised, and this was witnessed by real people.

Sometimes the witnesses were alone. Sometimes they were in small groups. Sometimes in large groups. Sometimes indoors. Sometimes outdoors. Sometimes expecting something; at other times not expecting anything at all.

Two of the most significant witnesses — James, the brother of Jesus, and Paul, the persecutor of the church — were not looking for Jesus. They did not imagine these appearances. They did not desire them. They were not in emotional states that could easily produce hallucinations or visions. And yet both independently became convinced that Jesus appeared to them. Both became leaders of the two great branches of early Christianity — James in the Jerusalem church and Paul in the Gentile mission. Both suffered greatly for their testimony, and both ultimately died for the faith they once opposed or misunderstood.

What we gain from the Gospels and Acts is not modern-style biography or precision journalism. What we gain is something far more important and historically stable:

a consistent, early, multi-witness claim that Jesus was crucified, buried, raised, and seen.

This proclamation appears:

- in the earliest creeds (1 Cor 15:3–5; Phil 2:6–11; Rom 1:3–4),

- in the seven undisputed letters of Paul,

- in all four Gospels,

- in Acts,

- in the Apostolic Fathers (1 Clement, Ignatius, Polycarp),

- and in the second-century apologists,

- and it continues as the heartbeat of Christian faith into the third century and beyond.

And we can trust the Gospels and Acts because they were written the exact same way other ancient writings were produced: through dictation, investigation, scribal collaboration, access to earlier accounts, and the patronage system of the Roman world. Far from making them unreliable, this situates them firmly inside the standard literary practices of their time.

The earliest Christians did not preserve every historical detail with modern precision. They preserved something far more essential — the central truth that the crucified Jesus appeared to people after his death, changed them, sent them, and launched a movement that transformed the world.

That unified testimony — appearing everywhere across the earliest Christian writings — is what the Gospels give us. And that is enough.