Nothing in the long history of Roman hostility toward Christians compares to what unfolded under Diocletian. Earlier persecutions were real and often severe, but under Diocletian the empire launched a decade-long, organized effort to dismantle Christianity itself. His political reforms, his religious worldview, and the system he created known as the Tetrarchy all collided with a rapidly growing Christian movement that refused to participate in Rome’s sacrificial life. The result was the largest and most systematic attempt ever made to extinguish the Christian name.

Understanding why the Great Persecution erupts with such force in 303 requires beginning with the political and religious system Diocletian put into place.

The Tetrarchy and the Ideology of Unified Rule

The formal Tetrarchy was established in AD 293, but the divine pairing of Diocletian and Maximian began earlier, when they ruled together as co-emperors. This divine alignment was already well established before Galerius and Constantius were added as Caesars.

A panegyric delivered before the Tetrarchy was formally created makes this divine association unmistakable:

Panegyrici Latini 10.4 (AD 289)

“Diocletian and Maximian, the one associated with Jupiter and the other with Hercules, govern the world with the majesty of the gods and the strength of heroes.”

This does not mean the emperors claimed personal divinity in the manner of Caligula or Domitian. They did not demand that sacrifices be offered to themselves. Instead, they presented themselves as ruling under Jupiter and Hercules, receiving divine legitimacy from these gods.

Under this political theology, unified worship was essential.

Sacrifice maintained the gods’ favor.

Refusal to sacrifice undermined the religious foundation that supported imperial stability.

When the Tetrarchy was formally created in AD 293, this divine framework expanded to include Galerius and Constantius as partners in the same cosmic order.

Diocletian’s Rise and His Vision for Stability

Fourth-century historian Aurelius Victor describes the turbulent origins of Diocletian’s reign:

Aurelius Victor, Epitome 39 (AD 360s)

“Diocletian, a man of low birth but keen mind, was hailed emperor by the army after Numerian had been treacherously slain.”

Diocletian inherited an empire weakened by half a century of civil war, invasion, inflation, and constant leadership changes. For him, restoring Rome required both administrative reconstruction and the renewal of Rome’s relationship with the gods.

His public image reflected this divine partnership. Inscriptions and coins throughout his reign repeatedly invoke the gods who upheld his rule:

IOVI CONSERVATORI

“To Jupiter the Protector”

HERCVLI DEFENSORI

“To Hercules the Defender”

GENIVS POPVLI ROMANI

“To the Guardian Spirit of the Roman People”

Reverse: IOVI AVGG — “To Jupiter of the Emperors,” showing Jupiter standing facing, head left, holding a scepter and Victory on a globe; eagle at his feet to the left

These inscriptions show not emperor worship but emperor alignment. Diocletian ruled under Jupiter’s protection, not as Jupiter himself. Christian refusal to sacrifice therefore struck at the foundation of the very system that legitimized the Tetrarchy.

A Rapidly Expanding Christian Movement

By the early fourth century, Christian communities were thriving. Eusebius describes this moment as a period of remarkable growth and public visibility:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.1.1 (AD 311–325)

“Before the persecution, the churches were at peace and multiplied everywhere. Rulers honored the Christians. Crowds assembled in the churches. New buildings rose from their foundations in every city.”

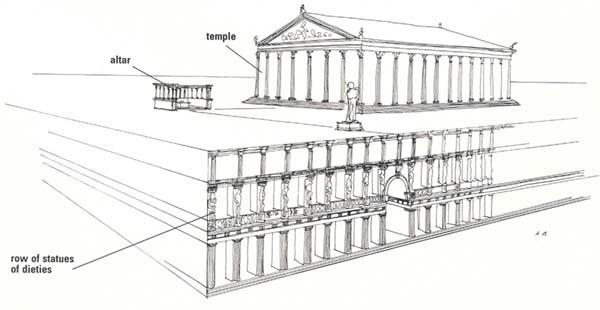

Archaeology confirms this account. Christian buildings became larger and more numerous; clergy gained public recognition; and Christians entered civic roles and even imperial service. A movement that once met quietly in homes now built large structures in major cities.

For an imperial system built upon unified sacrifice, this expanding Christian public life created unavoidable tension.

Galerius and the Push Toward Hostility

Lactantius, an eyewitness to these events, identifies Galerius as the chief instigator behind the coming persecution:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 11 (AD 313–315)

“Galerius, a man fierce in nature and hostile to the name of the Christians, urged the emperor daily to destroy the churches and to compel all to sacrifice.”

Galerius believed the empire’s troubles stemmed from neglect of the gods. Christian refusal to sacrifice was not private dissent but a direct challenge to Rome’s divine protection and the religious foundation of the Tetrarchy.

Diocletian hesitated for several years, but as pressure increased, he gradually shifted toward Galerius’s position.

Signs, Omens, and the Turning Point

Lactantius records a critical moment in AD 299, when the imperial household sought omens through a traditional sacrifice:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 10 (AD 313–315)

“When Diocletian and Galerius consulted the oracle, the diviners declared that the presence of Christians had disturbed the sacred rites.”

Christians in the imperial service did not participate in the gestures of reverence. The diviners blamed them for the failure of the ritual. In a political system where divine favor upheld the rulers, this carried enormous weight.

Eusebius describes the resulting shift in Diocletian’s attitude:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.2.1 (AD 311–325)

“Diocletian was persuaded that the time had come to wage war against the churches as if against enemies of the state.”

By AD 302, the decision was near.

By early AD 303, it was set.

The Destruction of the Nicomedia Church

The Great Persecution opened with a symbolic act carried out at the political center of the Eastern empire. On February 23, AD 303, Diocletian ordered the destruction of the major church in Nicomedia. Lactantius, writing only a decade later, gives us a vivid description of what happened that morning:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 12 (AD 313–315)

“On the morning of the day appointed for the celebration of the Terminalia, when the sun had not yet risen, the prefect together with tribunes and officers arrived at the church in Nicomedia, and having broken open the doors, they searched for the image of the god of the Christians, the Scriptures, and all that they used in their worship. When they found the Scriptures, they burned them; everything else they destroyed. The soldiers were allowed to seize whatever was found inside.”

The reference to the Terminalia, a festival dedicated to boundaries, is significant. Diocletian was drawing a line between the old religious order and the presence of Christianity in public life. By choosing this date, he signaled that the empire was redrawing its religious boundaries.

Eusebius, writing from within the Eastern provinces, confirms the same event from a different vantage point:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.2.4 (AD 311–325)

“The imperial edict commanded that the church in Nicomedia be leveled to the ground. Those who were present saw the building demolished from its foundations, and the sacred Scriptures committed to the flames.”

The two accounts, one Western and Latin (Lactantius) and one Eastern and Greek (Eusebius), give us the fullest picture we have of this opening blow.

The First Edict of 303

After the church was destroyed, Diocletian issued the first of four imperial laws. Lactantius reproduces the text in summary form, and his account is our primary source for its contents. According to him, the first edict contained four major provisions:

- All churches were to be destroyed.

- All Scriptures were to be burned.

- Christians were to lose legal rights and protections.

- Those in government positions were to be removed unless they sacrificed.

Here is the full text as preserved in Lactantius:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 13 (AD 313–315)

“An edict was published ordering that the assemblies of the Christians should be abolished, that their churches be torn down, that the Scriptures be burned, that those who held places of honor be degraded, that servants who persisted in the Christian faith be made incapable of freedom, and that those under accusation of following Christianity be not allowed to defend themselves in court.”

The brutality of the law becomes clear as Lactantius explains its underlying logic:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 13 (AD 313–315)

“The emperor believed that if he took away the opportunity of meeting for worship and destroyed their Scriptures, the religion itself could be abolished.”

This is the key sentence.

It shows the intent behind the Great Persecution: not merely to pressure Christians, but to erase the Christian movement by attacking its buildings, its Scriptures, and its legal status.

Refusal and Immediate Violence

Eusebius records the immediate resistance of some Christians in Nicomedia who tore down the imperial edict publicly:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.5.1 (AD 311–325)

“One of the Christians, moved with holy zeal, tore down the imperial edict that had been posted in a public place and put it into shreds as something profane and illegal.”

According to Eusebius, this man was arrested, tortured, and executed. His act represents one of the earliest martyrdoms of the Great Persecution.

Impact Across the Empire

The First Edict was carried out differently in East and West. In the East, where Galerius wielded influence, the laws were enforced strictly. Eusebius describes widespread destruction:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.2.5 (AD 311–325)

“Churches were torn down from top to bottom, and the sacred Scriptures were cast into the fire in the open marketplaces.”

In the West, Constantius enforced the law only minimally. Churches were destroyed, but he did not pursue Christians or burn Scriptures with the same severity. As Lactantius notes:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 15 (AD 313–315)

“Constantius, although he destroyed a few buildings, spared the Christians themselves and took no delight in their suffering.”

This divergence becomes much more pronounced in the years that follow. The edicts will be applied ruthlessly in the East and with comparative restraint in the West.

The Second Edict: Imprisonment of the Clergy

The First Edict had targeted buildings, Scriptures, and legal rights. When this failed to break Christian resolve, the imperial court issued a second command. This time, the goal was to dismantle the leadership of the churches.

Lactantius provides the clearest account:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 15 (AD 313–315)

“Diocletian published another edict, ordering that all the bishops and ministers should be thrown into prison.”

This marked a dramatic escalation. It was not aimed at all Christians, but at the entire structure that led and organized Christian communities.

Eusebius confirms the severity in the Eastern provinces:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.6.1 (AD 311–325)

“An edict was issued that all who were called ministers of the Word should be seized and committed to prison. And there was nothing mild in the execution of this command.”

Prisons filled rapidly. Eusebius writes:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.6.6 (AD 311–325)

“The prisons, which had previously held murderers and robbers, were now filled with bishops, presbyters, deacons, readers, and exorcists.”

This detail is important.

It shows the scale of the arrests and also how the empire quickly ran out of space to hold so many clergy.

The Third Edict: Forcing the Clergy to Sacrifice

By late 303, the prisons were overflowing. Rather than release the clergy, the imperial court issued a third edict directing that all imprisoned leaders be compelled to sacrifice.

Lactantius writes:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 16 (AD 313–315)

“A third edict commanded that all those in prison should be forced by every means to sacrifice.”

The phrase “by every means” implies torture, starvation, deprivation, and psychological pressure. Eusebius describes what happened in the East:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.6.8 (AD 311–325)

“Some endured every form of punishment in the attempt to force them to sacrifice; they suffered rackings, burnings, and all kinds of torment.”

Some clergy yielded. Many did not.

Those who refused were either kept imprisoned or executed.

The Fourth Edict: Universal Sacrifice

The fourth edict marked the full and final escalation. While the first three focused on property and clergy, the fourth edict extended to every Christian, commanding everyone to sacrifice to the gods or face punishment.

Lactantius states:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 17 (AD 313–315)

“A fourth edict was issued ordering that all persons, without exception, should sacrifice and taste the offerings.”

This was the heart of the Great Persecution.

For the first time in Roman history, a universal law required every Christian in the empire to sacrifice on pain of imprisonment, torture, or death.

Eusebius describes the impact:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.6.9 (AD 311–325)

“The command was given that all the inhabitants of the cities should be compelled to sacrifice and pour libations to the idols. Those who refused were subjected to various punishments.”

This edict brought the entire Christian population into direct conflict with the state.

Diverging Paths: East and West

The edicts applied to the whole empire, but enforcement differed dramatically.

The Western Provinces

Constantius, ruling in Gaul and Britain, enforced only part of the First Edict. He destroyed some church buildings but refused to persecute Christians themselves.

Lactantius remarks on this restraint:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 15 (AD 313–315)

“Constantius, though he destroyed a few buildings, did not harm the Christians and took no pleasure in their suffering.”

Under Constantine (after 306), persecution ceased entirely in the West.

The Eastern Provinces

The East was ruled first by Diocletian and Galerius, then by Galerius alone, and finally by Maximinus Daia. Here the edicts were enforced with full severity for nearly a decade.

Eusebius records the intense suffering that followed:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.9.1 (AD 311–325)

“In the regions under the rule of Maximinus an unbroken series of evils overwhelmed the Christians.”

This distinction between East and West explains why the Great Persecution lasted much longer in some regions. The universal sacrifice edict was enforced fiercely in the East and only lightly in the West.

The Scale of the Persecution

The four edicts created the most comprehensive legal assault Christianity ever faced:

• Churches destroyed

• Scriptures burned

• Legal rights removed

• Clergy imprisoned

• Clergy forced to sacrifice

• All Christians required to sacrifice

• Severe punishments for refusal

• Enforcement lasting nearly a decade in the East

This was not a short moment, like the requirement under Decius.

This was an attempt to eradicate Christian identity, its leadership, its Scripture, and its existence as a public movement.

The Height of the Persecution

After the fourth edict extended the requirement of sacrifice to every Christian in the empire, the persecution entered its most violent phase. This period, stretching from 303 through the early 310s in the East, produced scenes of cruelty unmatched in earlier Roman history. Eusebius and Lactantius, both eyewitnesses to portions of these events, provide detailed accounts of torture, imprisonments, and executions across the provinces.

Torture and Public Punishments

Eusebius describes how the authorities attempted to break Christian resolve with punishments designed to terrify the entire population.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.7.1 (AD 311–325)

“Some were scourged with whips, torn by the rack, and stretched out upon instruments of torture; some were burned with fire; others were crucified; some were beheaded; many were condemned to the mines or to the wild beasts.”

He emphasizes that these punishments were not isolated incidents but part of a coordinated effort:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.7.2 (AD 311–325)

“The cruelty of the governors was such that no words can adequately describe the variety and severity of their torments.”

Lactantius gives similar testimony, describing how the persecutors operated with deliberate intent to inflict suffering:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 18 (AD 313–315)

“Those who refused to sacrifice were tortured with every kind of instrument, and the cruelty of the judges seemed to have no end.”

These statements establish the environment of terror that spread through the Eastern provinces.

The Persecution in Egypt

Egypt experienced some of the most intense violence. Eusebius, who lived in Caesarea but had deep ties to Egypt, records the ferocity of the punishments in Alexandria:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.9.4 (AD 311–325)

“In Alexandria countless numbers were put to death. Some were beheaded; others burned; others cast into the sea; others given to the sword. The massacre continued day after day.”

He describes the courage of the martyrs:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.9.5 (AD 311–325)

“Not even the women were spared; they endured the same tortures as the men, and many met their end with remarkable courage.”

Egypt’s large Christian population meant that resistance was strong, and so was the response of the authorities. The violence continued for years.

The Suffering in Palestine

Eusebius’s Martyrs of Palestine (an appendix to his Ecclesiastical History) is one of the most detailed regional martyr narratives from the ancient world. In Part 4 of the main history, he describes the beginning of the violence:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.8.1 (AD 311–325)

“In Palestine, the persecutions were incessant. Every day brought new trials, and the judges devised new forms of torture.”

Some Christians were mutilated:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.8.3 (AD 311–325)

“Some had one eye gouged out, others had the joints of their ankles burned or severed, and thereafter were sent to the copper mines.”

Others were executed publicly:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.9.6 (AD 311–325)

“Many were beheaded or burned alive, so that the flames and the sword together took their daily victims.”

These passages give a vivid picture of the relentless and creative brutality that characterized the persecution in Palestine.

The Persecution Under Maximinus Daia

When Diocletian and Maximian abdicated in AD 305, the persecution did not end. Instead, it intensified in the East under Maximinus Daia, nephew of Galerius. Eusebius portrays his rule in especially dark terms:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.14.1 (AD 311–325)

“Maximinus, more cruel than any before him, inflamed with an unbounded hatred of the Christians, drove all to madness by his tyrannical measures.”

Under Maximinus, local officials were encouraged to compete in displays of cruelty, and mobs were incited to attack Christian communities.

Eusebius writes:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 9.2.1 (AD 311–325)

“The provinces under Maximinus were filled with executions; the tortures were carried out not only in the cities but in every village and district.”

This period saw some of the most gruesome executions in recorded Christian history.

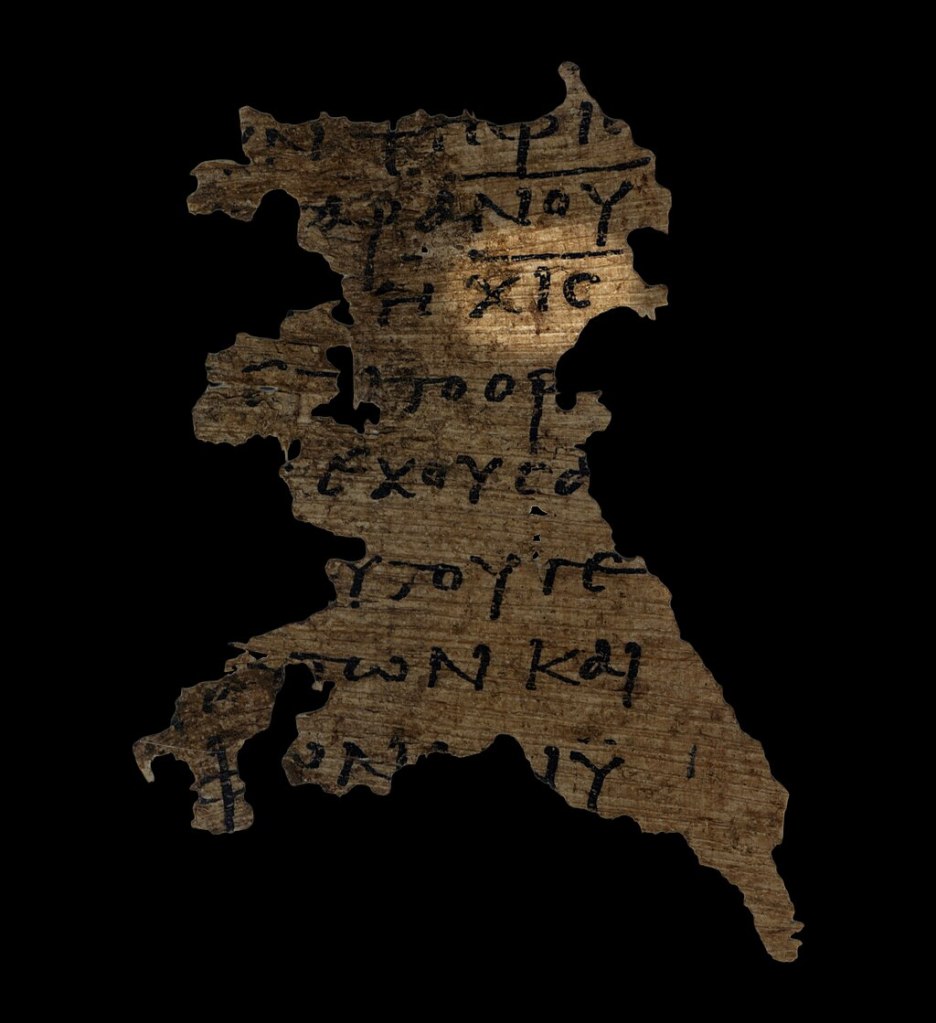

The Attempt to Eradicate Christian Scripture

One of the defining features of the Great Persecution was the attempt to eliminate Christian Scripture. This was a continuation of the First Edict, which targeted the sacred writings. Eusebius describes systematic searches:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.2.5 (AD 311–325)

“The sacred Scriptures were sought out with diligence, and when found, they were burned in the open squares.”

Lactantius adds:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 12 (AD 313–315)

“They burned the Scriptures with fire, believing that if the writings were destroyed the religion itself would perish.”

This attempt to eliminate Christian Scripture sets the Great Persecution apart from all earlier Roman actions.

The Persecution of Bishops and Teachers

Because bishops and teachers played a central role in community identity, the authorities targeted them specifically. Eusebius emphasizes how the persecution dismantled Christian leadership:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.6.6 (AD 311–325)

“The prisons, which had previously been filled with criminals, were now crowded with bishops, presbyters, deacons, readers, and exorcists.”

This was not incidental. Destroying the leadership was essential to the imperial plan. Without clergy, the Christian movement would lose cohesion. Without bishops, the sacraments could not be administered. Without teachers, instruction would cease.

Crucifixion, Mutilation, and the Mines

The Great Persecution included punishments that earlier emperors rarely used against Christians, including crucifixion. Eusebius documents instances where believers were nailed to crosses:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.7.5 (AD 311–325)

“Some were nailed to crosses, others were stretched out on them while still alive.”

Condemnation to the mines was common:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.12.1 (AD 311–325)

“Many were sent to the mines in Lebanon, Cilicia, and Palestine, with one eye mutilated and the joints of the ankles burned.”

These punishments were intended not only to kill but to degrade and terrorize.

The Emotional Weight of the Persecution

Eusebius breaks from his usual historical tone when describing the intensity of the suffering:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.12.3 (AD 311–325)

“It is impossible to recount the sufferings of the martyrs one by one, for the cruelty of the tyrants exceeded all bounds.”

This statement from an eyewitness underscores why the Great Persecution stands apart in scale and severity.

Galerius Struck with Illness

For nearly eight years after the first edict, the persecution raged most violently in the Eastern empire under Galerius and, later, Maximinus Daia. But in AD 310–311, Galerius was struck by a sudden and horrifying disease. Lactantius describes the illness in graphic detail, presenting it as divine judgment.

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 33 (AD 313–315)

“A malignant ulcer broke out in the secret parts of Galerius’s body, which gradually spread and ate into his vitals; from it issued a stench so foul that it was impossible for any man to endure it.”

The disease worsened over time:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 33 (AD 313–315)

“It became a torpid mass of corrupt flesh, breeding worms which no medical skill could remove. The surgeons cut away decayed pieces, but the wound only grew larger.”

Eusebius confirms the same picture:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.16.2 (AD 311–325)

“He was reduced to such a condition by an incurable disease that even his physicians could no longer approach him because of the unbearable stench.”

In this agony, Galerius made a decision no one expected.

Galerius Issues the Edict of Toleration (AD 311)

On April 30, AD 311, Galerius issued an imperial proclamation ending the persecution he had driven for a decade. Lactantius preserves the text in full. This is the earliest surviving imperial law granting legal status to Christianity.

Here is the complete edict, without abbreviation:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 34 (AD 313–315)

“Among the other measures that we have taken for the advantage of the empire, we had desired first of all to set everything right in accordance with the ancient laws and public discipline of the Romans. We therefore sought to restore the worship of the gods who sustain our empire, believing that the Christians had abandoned the religion of their ancestors.

Since, however, many persisted in their purpose, and since we saw that they neither paid reverence to the gods nor worshipped them, we therefore judged it necessary to command that they return to the practices of the ancients.

Yet because many obeyed not our decrees but endured all kinds of suffering, and because they showed that they could in no way be turned from their purpose, we are compelled by our utmost indulgence to extend pardon to them, so that once more they may be Christians and may build the places in which they gather, always provided that they do nothing contrary to good order.

It will be required of them that they pray to their God for our safety and that of the empire, and for their own, so that the state may be preserved in security on every side and that they may live in peace within their own dwellings.”

This is one of the most extraordinary documents in Roman history.

The man who insisted Christianity must be destroyed now publicly acknowledges:

- the Christians endured suffering,

- they could not be broken,

- and the imperial court now permits them to exist again.

After Galerius: Maximinus Daia Continues the Persecution

Although Galerius reversed imperial policy in 311, the violence did not end everywhere. In the Eastern provinces under Maximinus Daia, persecution continued until 313.

Eusebius describes Maximinus’s renewed hostility:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 9.1.2 (AD 311–325)

“Maximinus, inflamed with greater rage than before, would not permit the decree of Galerius to be carried out in his provinces.”

He incited cities to petition for continued persecution:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 9.2.4 (AD 311–325)

“Some of the cities sent formal petitions requesting that the Christians be forbidden to inhabit their lands. Maximinus eagerly granted such requests.”

It is only after Maximinus’s military defeat in 313 that Christianity finally receives full legal protection in the East.

Constantine and Licinius End the Persecution (AD 313)

In early 313, Constantine and Licinius met in Milan and jointly agreed to extend full toleration across the empire. Although the exact text survives in a provincial copy preserved by Lactantius, its purpose is clear: to restore full freedom to Christian communities.

The proclamation states:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 48 (AD 313–315)

“We resolved to grant both to the Christians and to all others full authority to observe whatever worship they choose, so that whatever divinity resides in heaven may be favorable to us and to all who are under our authority.”

By this point:

- Constantius had always been mild in the West

- Constantine ended persecution in 306

- Galerius ended the persecution in 311 in his realms

- Maximinus’s defeat in 313 ended the last violent enforcement

Thus, AD 313 marks the end of the Great Persecution, nearly ten years after it began.

The Long Aftermath

Eusebius depicts the rejoicing of Christian communities once the persecution ceased:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 10.2.1 (AD 311–325)

“After the tyrants had been removed, God wiped away every tear from their eyes, and the festival of freedom was celebrated throughout the cities.”

Churches were rebuilt.

Leaders returned from exile.

Scriptures were recopied.

The memory of the martyrs became foundational to Christian identity.

The Great Persecution had failed.

Instead of destroying Christianity, it had purified and strengthened it.

Eyewitness Martyr Testimonies and Christian Voices During the Persecution

To understand the intensity of the Great Persecution, it is necessary to hear the voices of those who lived through it. Beyond the narratives of Lactantius and Eusebius, several eyewitness accounts survive describing the sufferings of Christians across the empire. These texts record the trials, tortures, and executions of believers who endured the decade between 303 and 313. Their voices form one of the richest collections of primary sources from early Christian history.

The Martyrs of Palestine

Eusebius’s Martyrs of Palestine is among the most detailed eyewitness accounts of martyrdom from the ancient world. Written between AD 311 and 313, it describes the executions he witnessed in Caesarea and the surrounding regions.

Apphianus

The story of Apphianus is among the most vivid:

Eusebius, Martyrs of Palestine 4.7–8 (AD 311–313)

“Apphianus was struck repeatedly on the face, yet his courage did not falter. When they wrenched his limbs with instruments of torture, he remained unshaken in his purpose. They wrapped his feet in linen steeped in oil and set them on fire. Then they bound heavy stones to him and cast him into the sea.”

Procopius

Eusebius also records the martyrdom of Procopius, a reader in the church:

Eusebius, Martyrs of Palestine 1.2 (AD 311–313)

“Procopius was brought before the governor. When he refused to sacrifice, he was immediately beheaded, sealing his testimony with the sword.”

Agapius and the Beasts

One of the most dramatic scenes takes place in the amphitheater:

Eusebius, Martyrs of Palestine 6.3 (AD 311–313)

“Agapius was sentenced to the wild beasts. When he confessed Christ boldly, the beasts were let loose upon him, and he met his end with steadfast courage.”

Pamphilus and the Scholars

Eusebius’s own mentor and teacher, Pamphilus of Caesarea, was martyred along with a group of scholars:

Eusebius, Martyrs of Palestine 11.1 (AD 311–313)

“Pamphilus, the most admirable of men, endured imprisonment for two years. After countless tortures, he and his companions were put to death.”

The Alexandrian Martyrs

Alexandria remained one of the largest Christian centers in the empire, and the persecution struck it with unusual violence.

Eusebius writes:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.9.6 (AD 311–325)

“Some were burned, some were drowned, some beheaded, some given to the sword, and others cast into the fire. The massacre continued day after day.”

Peter of Alexandria

Peter, bishop of the city, was executed in AD 311:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.13.2 (AD 311–325)

“Peter, who presided over the church in Alexandria, was arrested and beheaded, giving a noble example to the flock.”

Phileas of Thmuis

Phileas, another Egyptian bishop, wrote an eyewitness letter describing the prisons and tortures. Eusebius preserves part of it:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.10.2–3 (AD 311–325)

“Phileas wrote in detail of the sufferings of the blessed martyrs: how they stood firm under countless torments, how the judges exhausted themselves in devising new forms of cruelty, and how the martyrs endured everything with admirable patience.”

The Egyptian Confessors Sent to the Mines

Among the most horrifying scenes is the mutilation and transportation of Egyptian confessors to the mines of Palestine.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.8.3 (AD 311–325)

“Some had the one eye gouged out, others had the joints of their ankles burned or severed. Then they were sent to the mines, bearing in their bodies the marks of Christ’s sufferings.”

These punishments were intended to break morale and terrorize Christian communities.

Martyrdom in Syria and Asia Minor

While Palestine and Egypt preserve the richest martyr narratives, persecution also raged throughout Syria and Asia Minor.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.12.1 (AD 311–325)

“Throughout Syria and the regions beyond, countless numbers were sent to the mines after being mutilated in their eyes and feet.”

And in a passage describing Maximinus Daia’s reign:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 9.2.1 (AD 311–325)

“The provinces under Maximinus were filled with executions, both in the cities and in the villages.”

The Martyrdom of Lucian of Antioch

Lucian, a priest and renowned biblical scholar, was executed in AD 312 at Nicomedia.

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 9.6.3 (AD 311–325)

“Lucian, a man distinguished for his skill in the divine Scriptures, sealed his testimony at Nicomedia, offering a noble example of endurance.”

Methodius of Olympus

Methodius, an important theological writer, was martyred near the end of Galerius’s reign. Though Eusebius does not describe the details, Jerome preserves the tradition:

Jerome, On Illustrious Men 83 (AD 392)

“Methodius, bishop of Olympus, suffered martyrdom at the end of the reign of Galerius.”

His death represents the loss of one of the era’s great Christian thinkers.

Peter of Alexandria’s Pastoral Letters

Peter, the martyred bishop of Alexandria, wrote pastoral letters during the persecution addressing those who had lapsed under torture.

Peter of Alexandria, Canonical Letter 4 (AD 306–311)

“Those who betrayed the faith under the compulsion of torture must be received with mercy after they have shown due repentance, for they fell under force and not of their own will.”

These letters show how deeply the persecution impacted Christian pastoral life and discipline.

Restoration Inscriptions and Archaeological Witnesses

After the persecution ended, inscriptions commemorated the rebuilding of destroyed churches. One from North Africa reads:

Cirta inscription (Numidia), c. 315

“Restored from the ruins of the persecution.”

Archaeological evidence also preserves burn layers, smashed furnishings, and remnants of hidden Scriptures, confirming the literary accounts of destruction.

Conclusion: The Decade Rome Tried to Erase the Church

The Great Persecution stands alone in the history of the Roman Empire. Earlier persecutions were real and often severe, but none matched the scale, duration, coordination, or intent of the measures launched between AD 303 and 313. Across the Eastern empire especially, Christians faced a comprehensive legal and physical assault designed not merely to punish them but to erase their Scriptures, dismantle their leadership, destroy their churches, and compel all believers to abandon their faith.

The laws progressed step by step until the entire Christian population fell under their weight. Churches were torn down, Scriptures burned, clergy imprisoned, clergy tortured, and finally all Christians forced to sacrifice under threat of death. The edicts touched every element of Christian life.

The purpose is stated clearly in the primary sources. Lactantius records Diocletian’s reasoning with stark precision:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 13 (AD 313–315)

“He believed that if he took away the opportunity of meeting for worship and destroyed their Scriptures, the religion itself could be abolished.”

No earlier emperor had attempted something so broad, so systematic, or sustained for so many years.

The Witness of the Martyrs

The eyewitness narratives from the period show Christians suffering with extraordinary courage. These testimonies were not written decades later. They are contemporary accounts of real people, recorded by those who saw them.

Apphianus in Caesarea stood firm under repeated blows, brutal torture, and finally death by drowning:

Eusebius, Martyrs of Palestine 4.7–8 (AD 311–313)

“Apphianus was struck repeatedly on the face, yet his courage did not falter. When they wrenched his limbs with instruments of torture, he remained unshaken in his purpose. They wrapped his feet in linen steeped in oil and set them on fire. Then they bound heavy stones to him and cast him into the sea.”

Procopius was executed in a single stroke for refusing to sacrifice.

Agapius went to the beasts and met them with fearless confession.

Pamphilus, mentor of Eusebius, endured two years of imprisonment before being put to death.

Phileas of Thmuis described the judges exhausting themselves in inventing new torments.

The Egyptian confessors bore mutilated bodies as marks of their faith.

Lucian of Antioch sealed his testimony at Nicomedia.

Methodius of Olympus, a profound Christian thinker, was killed late in the persecution.

Peter of Alexandria guided his flock with pastoral letters, then faced martyrdom himself.

These names, and many more whose stories survive only in fragments or inscriptions, represent a generation of Christians who stood firm when Rome sought to destroy their faith at its roots.

Eusebius summarizes their endurance with solemn simplicity:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 8.13.12 (AD 311–325)

“In all these trials the athletes of religion shone with patient endurance, for they held fast to their faith with unshaken resolve.”

The Failure of the Persecution

Despite the severity of the laws and the brutality of their enforcement, the persecution ultimately failed.

It failed because Christians refused to abandon their faith.

It failed because Scripture was recopied even while authorities burned it.

It failed because the bishops and clergy held the communities together under unimaginable pressure.

It failed because Christian identity proved stronger than imperial coercion.

Galerius, the chief architect of the persecution, acknowledged this failure publicly in his Edict of Toleration:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 34 (AD 313–315)

“Since many obeyed not our decrees but endured all kinds of suffering, and since they showed that they could in no way be turned from their purpose, we are compelled by our utmost indulgence to extend pardon to them.”

The persecutor confessed that he could not break the Christians.

He allowed them once again to gather, rebuild, and worship.

Restoration After the Storm

Once Maximinus Daia was defeated in 313, the last remnants of persecution collapsed. Constantine and Licinius extended full religious freedom to all:

Lactantius, On the Deaths of the Persecutors 48 (AD 313–315)

“We resolved to grant both to the Christians and to all others full authority to observe whatever worship they choose, so that whatever divinity resides in heaven may be favorable to us and to all who are under our authority.”

The rebuilding began immediately. Eusebius describes the rejoicing of Christian communities:

Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 10.2.1 (AD 311–325)

“After the tyrants had been removed, God wiped away every tear from their eyes, and the festival of freedom was celebrated throughout the cities.”

Inscriptions across the empire testify to this restoration:

Cirta inscription (Numidia), c. 315

“Restored from the ruins of the persecution.”

Churches were rebuilt larger than before. Scriptures were recopied. Clergy returned from exile. Communities gathered openly. The names of the martyrs were honored. The memory of their courage became foundational to Christian identity and theology.

A Final Reflection

The Great Persecution did not destroy Christianity. It revealed its strength.

It did not silence Christian witness. It amplified it.

It did not weaken the church. It purified and deepened it.

The empire had attempted to extinguish the Christian faith by burning its Scriptures, breaking its leadership, and torturing its people. Instead, Christianity emerged from this decade more unified, more resilient, and more firmly rooted in the conviction that no earthly power could overcome the truth of the gospel.

When the persecution ended, Christianity did not merely survive.

It stood on the threshold of transformation.

Within a single generation, emperors who once sought its destruction would support its growth and honor its martyrs.

The Great Persecution remains one of the defining moments in Christian memory:

a testimony to suffering, endurance, and the unwavering faith of those who stood firm when the world pressed hardest against them.