40 % Growth Then, 5 % Growth Now — What We Must Learn Anew

When Hadrian (reigned AD 117 – 138) succeeded Trajan, he inherited an empire stretched thin by conquest. He halted Trajan’s eastern campaigns, fortified the frontiers, and poured his energy into unifying the world through Roman law, architecture, and religion. His adopted son, Antoninus Pius (reigned AD 138 – 161), would later rule in peace and prosperity. Yet Hadrian’s program of cultural uniformity provoked catastrophe in Judea —the Bar Kokhba Revolt—whose scars still mark the land. Out of that ruin the first great Christian writers of defense arose, rebuilding faith with words rather than weapons.

1. The Seeds of Revolt — Why It Began

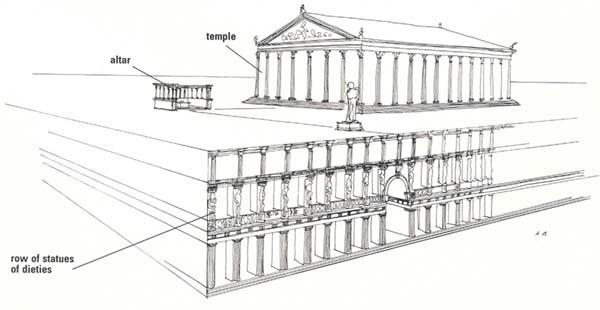

Aelia Capitolina and the Ban on Circumcision

“At Jerusalem he founded a city called Aelia Capitolina, and on the site of the Temple of God he raised another temple to Jupiter. He ordered that no one be circumcised. This brought on a war of no slight importance nor of brief duration.”

— Cassius Dio, Roman History 69.12.1–2 (c. AD 220).

“He forbade castration and circumcision; if anyone committed such an act he was punished. The Jews, being ordered not to mutilate their genitals, revolted against him.”

— Historia Augusta, Hadrian 14.2–3 (c. AD 300).

“Hadrian founded in its place a city, naming it Aelia Capitolina, and raised a new temple to Jupiter on the site of the Temple of God. … But when they opposed him for these things, another war broke out.”

— Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 4.6.1–2 (c. AD 310).

Hadrian’s decrees turned covenantal faith into treason and desecrated the holiest ground of Israel.

Messianic Expectation

“You curse in your synagogues those who believe in Christ, and after Him you now choose a man, a leader, and call him the Messiah.”

— Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 31 (c. AD 155)“A wicked man arose, who decreed evil decrees against Israel. He said to them: ‘You shall not circumcise your sons.’ Bar Koziba arose and said: ‘I am the Messiah.’”

— Jerusalem Talmud, Ta’anit 4:5 (c. AD 400–425, preserving 2nd-cent. tradition).

“Rabbi Akiva, when he saw Bar Koziba, said: ‘This is the King Messiah.’ Rabbi Yohanan ben Torta said to him: ‘Akiva, grass will grow on your cheeks and the Son of David will not yet have come.’”

— Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 97b (c. AD 500, preserving 2nd-cent. tradition).

Akiva’s hope inspired the revolt; ben Torta’s warning foretold its ruin.

Hope to Rebuild the Temple

“The Jews were in a frenzy, thinking that they could rebuild their temple, and they began war.”

— Cassius Dio, Roman History 69.13.1 (c. AD 220).

Faith collided with empire; by AD 132 Judea was in flames.

2. The War Unfolds — Rome and the Wrath of Empire

Bar Kokhba’s Government

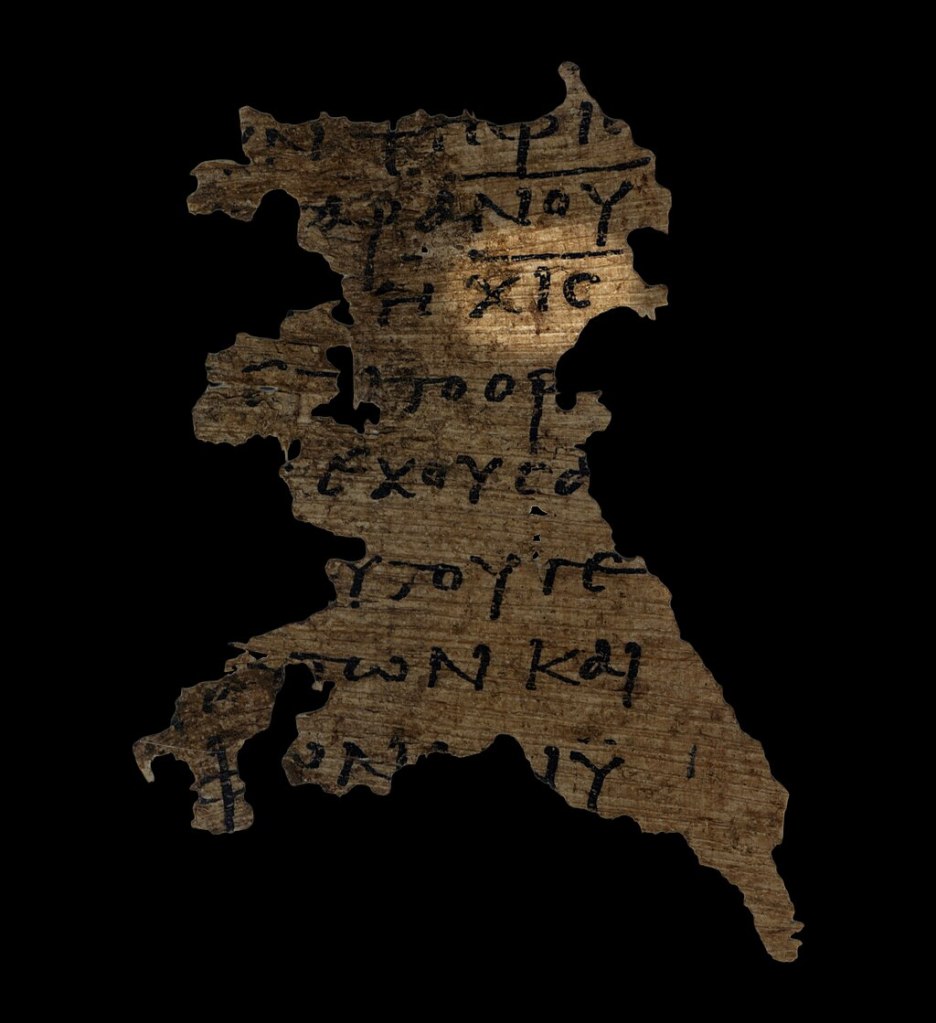

Letters from the Judean desert reveal both faith and fear:

“Shimon bar Kosiba to Yehonathan ben Be’ayan: Send the men from you with arms, and hurry them. If you do not send them, you will be punished.”

— Bar Kokhba Letter 24, Cave of Letters (c. AD 133).

“I have sent you two donkeys. Send back with them wheat, barley, wine, and oil.”

— Bar Kokhba Letter 31 (c. AD 133).“When the war had been stirred up again in the time of Hadrian, and the Jews were in revolt under Bar Chochebas, their leader, who claimed to be a star that had risen, the Christians in Jerusalem were driven away again from the land of Judea, so that the church of God was composed of Gentiles only.

And the Jewish Christians suffered greatly for not joining in the revolt nor denying Christ.”

— Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 4.6.2–3 (c. AD 310)

Coinage proclaimed their leader and their purpose.

| Side | Image | Inscription (transliteration) | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | Temple façade with Ark | שמעון (Shim‘on) | “Simon [Bar Kokhba]” |

| Reverse | Lulav and Etrog (symbols of the Feast of Tabernacles) | לחרות ירושלם (Leḥerut Yerushalayim) | “For the freedom of Jerusalem” |

| Side | Image | Inscription (transliteration) | Translation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | Ram | שמעון (Shim‘on) | “Simon [Bar Kokhba]” |

| Reverse | Palm tree | לחרות ישראל (Leḥerut Yisra’el) | “For the freedom of Israel” |

Bethar — The Last Fortress

The revolt’s final stronghold was Bethar (modern Battir), a hilltop fortress about six miles southwest of Jerusalem guarding the approach to the Shephelah valley. It had served as a Hasmonean citadel generations earlier and was heavily fortified by Bar Kokhba as his capital and final refuge. Jewish sources remembered it as a city of scholars and soldiers, filled with Torah scrolls and defenders who believed the Messiah himself commanded them. When Roman legions closed in, thousands of refugees from surrounding villages crowded within its walls, making Bethar both the military and symbolic heart of the rebellion.

Rome’s Counter-Attack and Cruelty

“At first, Tineius Rufus, who was governor of Judea, and the others who held command there tried to check the outbreak, but they were unable to do so. [Lusius] Severus was sent against them, but he also could not subdue them. Then Hadrian dispatched Julius Severus from Britain with many others from the neighboring provinces, and he crushed the whole of Judea with great difficulty and much bloodshed.”

— Cassius Dio, Roman History 69.13.1–2 (c. AD 220).

“Fifty of their most important strongholds and nine hundred and eighty-five of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. Five hundred and eighty thousand men were slain … and the number that perished by famine, disease, and fire was past finding out.”

— Cassius Dio, Roman History 69.14.1–2 (c. AD 220).

“Thus the whole of Judea was made desolate, and the few that were left perished by hunger, disease, and fire. The corpses were so many that no one was left to bury them.”

— Eusebius, Chronicon (fragment, year of Abraham 2148 = AD 135).

Following the city’s fall, Roman authorities even forbade burial of the dead — a final humiliation intended to erase hope itself. Jewish tradition remembers that years later, permission was finally granted under Antoninus Pius, when the bodies, miraculously undecayed, were interred with honor. The rabbis commemorated this act of mercy by adding a permanent blessing to their prayers: “Blessed is He who is good and does good.”

“The Gentiles slew the people of Bethar until their blood flowed into the Great Sea, and the bodies were not buried. Years later, the corpses did not decay, and when permission was given to bury them, the Sages in Yavneh ordained the blessing, ‘Blessed is He who is good and does good.’”

— Jerusalem Talmud, Ta’anit 4.8 (c. AD 400–425, preserving 2nd-cent. tradition).

Bethar’s fall marked the end of the revolt and the last gasp of Jewish independence until modern times. At Bethar the Romans killed without mercy; only later, under a more humane emperor, were the dead finally granted rest. Excavations show burn layers and projectiles matching Roman siege tactics.

3. The Consequences for Jews and Christians

“Thus nearly all Judea was made desolate, and Hadrian, in his anger, ordered that the name of the nation should be changed, so that it might not be remembered.”

— Cassius Dio, Roman History 69.14.3 (c. AD 220).

Jerusalem became Aelia Capitolina; Judea became Syria Palaestina. Jews were barred even from viewing their city.

“From that time the whole nation was prohibited by law from entering Judea, and the Christians who were of Hebrew origin then departed and went elsewhere.”

— Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 4.6.3 (c. AD 310).

The Jerusalem church — once Jewish-led — became entirely Gentile.

“Jerusalem has now been laid waste, and none of you are permitted to enter there. Such things have happened, as the prophets foretold, that it might be known that the desolation of Zion would last until the end.”

— Justin Martyr, Dialogue with Trypho 16 (c. AD 155).“Bethar was captured, and Bar Koziba was killed. They brought his head to Hadrian.”

— Jerusalem Talmud, Ta’anit 4.8 (c. AD 400–425, preserving 2nd-century memory)Later Rabbinic Re-evaluation of Bar Kokhba

“Bar Koziba ruled two and a half years and then said to the rabbis, ‘I am the Messiah.’

They answered him, ‘It is written that the Messiah shall smell and judge. Let us see whether you can discern in that way.’

When they saw that he could not, they killed him.”

— Lamentations Rabbah 2.4 (compiled c. AD 400, preserving 2nd-century tradition)This later rabbinic legend reflects how Jewish teachers, looking back on the disastrous revolt, rejected Bar Kokhba’s messianic claim. Ancient Jewish interpretation took the phrase “smell in the fear of the Lord” to mean that the true Messiah would have a supernatural discernment—the ability to “smell” truth and judge rightly.

It stands in striking contrast to Rabbi Akiva’s earlier support and shows that even within Judaism, the revolt came to be remembered as a tragic mistake.

A Day of Mourning Added to the Jewish Calendar

In rabbinic tradition the devastation of Bethar and the final desolation under Hadrian were fixed in collective memory. The Mishnah records that the fall of Bethar occurred on the Ninth of Av (9 Av) — the same date on which both the First and Second Temples had fallen.

On the modern calendar, Tisha B’Av usually falls in late July or early August — for example, in 2025 it fell from sunset on August 2 to nightfall on August 3.

From this time forward, Tisha B’Av became the national fast commemorating all three destructions: the Temple of Solomon, the Temple of Herod, and the last fortress of Bar Kokhba.

“On the Ninth of Av the decree was made that our fathers should not enter the land; the First Temple was destroyed, and the Second Temple, and Bethar the great city was captured, and the city was plowed as with a plowshare.”

— Mishnah, Ta’anit 4.6 (c. AD 200, preserving earlier memory).

When Jews Were Allowed to Return

For nearly two centuries after Hadrian, Jews were banned from Jerusalem except on the single day each year — Tisha B’Av — when they were permitted to approach the ruins and weep. The ban remained in force through the reigns of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius and continued under successive emperors.

After the Christianization of the empire, the prohibition was renewed by Constantine and his successors, who maintained Aelia Capitolina as a Christian city. Only under the early Muslim caliphs in the seventh century AD — after the conquest of Palestine by Caliph ʿUmar ibn al-Khattāb (c. AD 638) — were Jews once again allowed to resettle and live permanently in Jerusalem. Small Jewish communities then re-established themselves in the city and surrounding Judea for the first time since Hadrian’s decree.

4. Aftermath — From Swords to Books

After the fires of Judea were extinguished, Christians across the empire began defining their identity in writing.

What Rome destroyed in stone, the early church rebuilt in testimony.

These were the first defenders of the faith — the Apologists — men who addressed emperors directly, explaining that the followers of Christ were not enemies of the state but citizens of a heavenly kingdom.

Quadratus of Athens (c. AD 125, to Emperor Hadrian)

Quadratus is considered the earliest Christian apologist.

Ancient tradition identifies him as a disciple of the apostles and possibly a leader in Athens or Asia Minor.

His Apology—now preserved only in a fragment quoted by Eusebius—was written directly to Emperor Hadrian around AD 125.

It marks the moment when Christianity first spoke publicly to imperial power in its own defense.

“The works of our Saviour were always present, for they were true: those who were healed and those who were raised from the dead were seen not only when they were healed and when they were raised, but also for a long time afterwards; some of them survived even into our time.”

— Quadratus, Apology (fragment in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 4.3.2, c. AD 125)

Key Insights

- Christianity appealed to historical evidence, not mystery.

- Living eyewitnesses of Jesus’ miracles were still remembered.

- The faith was not superstition but sober truth confirmed by real people.

Quadratus’s voice rose from the same decades that saw Hadrian rebuild Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina.

While Rome celebrated new marble temples, Quadratus pointed to a living temple — the memory of the risen Christ in human witnesses.

The Epistle of Barnabas (c. AD 120–130, likely Alexandria or Syria)

Though attributed to “Barnabas,” the companion of Paul, this letter was almost certainly written later by an anonymous Christian teacher, probably in Alexandria.

Its audience was a mixed community of Jewish and Gentile believers struggling to understand whether the Law of Moses still bound Christians.

The author insists that the old covenant has been replaced by a spiritual one, that rituals and sacrifices were misunderstood symbols, and that true circumcision is of the heart.

He writes in the shadow of Hadrian’s decrees banning circumcision and rebuilding Jerusalem as a pagan city.

In this context, his message is unmistakable: Christianity, not Judaism, preserves the true covenant of God.

Opening Exhortation (Chs. 1–2)

“Greetings, sons and daughters, in the name of the Lord who loved us, in peace.

Because the Lord has granted you an abundance of spiritual knowledge, I rejoice greatly and beyond measure in your blessed and glorious spirits.

For this reason I have written to you briefly, that you might be made perfect in your faith and knowledge.

Therefore let us take heed, lest we be found as it is written, ‘Many are called, but few are chosen.’”

— Barnabas 1.1–4

The Covenant and the Rejection of the Literal Law

“Take heed to yourselves, and be not like some, heaping up your sins and saying that the covenant is both theirs and ours.

It is ours; but in this way did they finally lose it, after Moses had already received it.

For the Lord has written it again on our hearts.”

— Barnabas 4.6–8

The writer insists that covenant privilege passed to those who obey in spirit, not in ritual.

His argument echoes Jeremiah 31’s promise of a “new covenant written on the heart.”

Circumcision and the New Law

“He has abolished these things, that the new law of our Lord Jesus Christ, free from the yoke of constraint, might have its own offering not made by human hands.

So we are they whom He brought into the new law; no longer bound by circumcision.

For He has said that the circumcision with which they trusted is abolished.

He has circumcised our ears that we might hear His word and believe.”

— Barnabas 9.4–7

The Path of Light (Chs. 18–20)

“There are two paths of teaching and of power: one of light, and one of darkness.

The path of light is this: you shall love the one who created you; you shall glorify the one who redeemed you from death.

You shall be simple in heart and rich in spirit.

You shall not exalt yourself, you shall not hate anyone; you shall reprove some, you shall pray for others, and you shall love others more than your own life.”

— Barnabas 18.1–3, 20.2

Closing Words

“Since, then, you now understand the good things of the Lord, be filled with them.

If you do these things, you will be strong in the faith, and you will be found perfect in the last day.

The God who rules over the universe will give you wisdom, understanding, knowledge, and eternal life, through His Servant, Jesus Christ, to whom be glory forever and ever. Amen.”

— Barnabas 21.1–3

Key Insights

- The writer speaks to a generation caught between Judaism and Christianity, insisting that God’s covenant has moved from the physical to the spiritual.

- He turns Hadrian’s desecration of Jerusalem into a theological truth: the Temple and its sacrifices were destined to end, giving way to a new and living covenant.

- The Epistle of Barnabas shows Christianity defining itself not by rebellion, but by a renewed inner faith and moral life.

- Its tone is pastoral and exhortational — teaching that salvation is found not through outward religion but through obedience of the heart and love of neighbor.

Aristides of Athens (c. AD 125–140, to Antoninus Pius)

Aristides, a philosopher from Athens, presented his Apology to Emperor Antoninus Pius around AD 125–140.

He had converted from philosophy to Christianity and sought to defend it as the truest form of reason and virtue.

The Apology survives in Syriac, Armenian, and Greek fragments.

Dedication

“To the Emperor Caesar Titus Hadrianus Antoninus Augustus Pius, from Marcianus Aristides, a philosopher of Athens.

I, O King, by the inspiration of God, have come to this conclusion, that the universe and all that is in it is moved by the power of another… Wherefore I… have no wish to worship any other than God, the living and true, and I have searched carefully into all the races of men and tested them, and this is what I have found.”

— Aristides, Apology 1

Survey of Humanity (Chs. II – XIV)

Barbarians – idol worshippers.

Greeks – immoral gods.

Egyptians – animal worship.

Jews – monotheists yet bound to angels, sabbaths, and rituals.

Christians (Full Text Chs. XV–XVI)

XV

“But the Christians, O King, reckon the beginning of their religion from Jesus Christ, who is named the Son of God Most High; and it is said that God came down from heaven, and from a Hebrew virgin took and clothed Himself with flesh, and that the Son of God lived in a daughter of man.

This is taught in the gospel, as it is called, which a short time ago was preached among them; and you also, if you will read therein, may perceive the power which belongs to it.This Jesus, then, was born of the race of the Hebrews; and He had twelve disciples, in order that a certain dispensation of His might be fulfilled.

He was pierced by the Jews, and He died and was buried; and they say that after three days He rose and ascended to heaven.Thereupon these twelve disciples went forth into the known parts of the world, and taught concerning His greatness with all humility and soberness.

And those then who still observe the righteousness which was enjoined by their preaching are called Christians.And these are they who more than all the nations of the earth have found the truth.

For they acknowledge God, the Creator and Maker of all things, in the only-begotten Son and in the Holy Spirit; and besides Him they worship no other God.They have the commandments of the Lord Jesus Christ Himself graven upon their hearts; and they keep them, looking for the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.

They do not commit adultery or fornication; they do not bear false witness; they do not covet the things of others; they honor father and mother; they do good to those who are their neighbors; and they judge uprightly.

They do not worship idols made in the likeness of man.

Whatever they would not wish others to do to them, they do not practice themselves.They do not eat of the food offered to idols, for they are pure.

They comfort their oppressors and make them their friends; they do good to their enemies.Their women are pure as virgins, and their daughters are modest.

Their men abstain from all unlawful union and from all uncleanness, in the hope of a recompense to come in another world.”

XVI

“They love one another.

They do not turn away a widow, and they rescue the orphan.

He who has gives ungrudgingly to him who has not.If they see a stranger, they take him under their roof, and they rejoice over him as over a real brother.

If anyone among them is poor and needy, and they have no spare food, they fast two or three days in order to supply the needy with their necessary food.They observe scrupulously the commandments of their Messiah.

They live honestly and soberly, as the Lord their God ordered them.

They give thanks to Him every hour, for all meat and drink and other blessings.If any righteous man among them passes away from the world, they rejoice and thank God, and escort his body with songs and thanksgiving as if he were setting out from one place to another.

When a child has been born to one of them, they give thanks to God; and if it chance to die in childhood, they praise God mightily, as for one who has passed through the world without sins.

If anyone of them be a man of wealth, and he sees that one of their number is in want, he provides for the needy without boasting.

And if they see a stranger, they take him under their roof and rejoice over him as over a brother; for they do not call them brethren after the flesh, but brethren after the Spirit and in God.

Whenever one of their poor passes away from the world, each of them, according to his ability, gives heed to him and carefully sees to his burial.

Such is the law of the Christians, O King, and such is their manner of life.

And verily, this is a new people, and there is something divine in them.”

Key Insights

- Aristides presents the earliest surviving portrait of Christianity as both moral philosophy and divine revelation.

- His focus is not political defense but moral demonstration: Christians prove their truth by their purity, compassion, and generosity.

- His final words — “this is a new people, and there is something divine in them” — sum up the astonishment of the pagan world.

- Written during Antoninus Pius’s peaceful reign, the passage shows the church living out its faith in the shadow of Hadrian’s destruction — rebuilding not cities, but communities of love.

Justin Martyr (c. AD 150–160, to Antoninus Pius)

Background

Justin was born in Samaria, educated in Greek philosophy, and converted to Christianity after discovering in Christ the truth that philosophers sought but never found.

Writing from Rome, he addressed his First Apology to Emperor Antoninus Pius, his sons Verissimus (Marcus Aurelius) and Lucius Verus, and to the Senate and people of Rome.

His goal was to defend Christians from unjust persecution by showing that their faith was the highest expression of reason (logos), morality, and civic virtue.

- Note how Justin declares that yes Christians are guilty of atheism in Roman eyes and therefore worthy of capital punishment. He is trying to get the emperor to see that Christians are his best citizens and guilty of no ethical crimes. He is trying to get Christians legal religious status.

Introduction of the Apology

“To the Emperor Titus Ælius Hadrian Antoninus Pius Augustus Cæsar,

and to Verissimus his son, philosopher, and to Lucius the philosopher,

the natural son of Cæsar and adopted son of Pius, lover of learning,

and to the sacred Senate, and to the whole people of the Romans—

on behalf of those of all nations who are unjustly hated and persecuted, I, Justin, one of them, have composed this address and petition.Reason requires that those who are found not living wickedly, nor practicing evil, should not be unjustly accused; nor, when they have been accused, condemned without inquiry and without knowledge of the truth.

For not by the mere name has anyone been proved good or bad, but by the actions which each has done.”

— Justin Martyr, Apology 1.1–2 (c. AD 155)

On Unjust Persecution and True Allegiance

“If anyone, when he is examined, is found guilty, let him be punished as an evil-doer; but if he is found guiltless of the charges laid against him, let him be acquitted, since it is unjust to punish the guiltless.

We do not seek to escape punishment if we are convicted as wrongdoers, but we ask that the charges against us be examined.”

— Justin Martyr, Apology 1.3–4 (c. AD 155)

“We are accused of being atheists. We confess that we are atheists, so far as gods of this sort are concerned, but not with respect to the most true God, the Father of righteousness and temperance and the other virtues.”

— Justin Martyr, Apology 1.6 (c. AD 155)

On the Transformation of the Believers

“We who once delighted in fornication now embrace chastity alone;

we who used magical arts now consecrate ourselves to the good and unbegotten God;

we who valued above all things the acquisition of wealth and possessions now bring what we have into a common stock and share with everyone in need;

we who hated and slew one another, and refused to share our hearth with those of another tribe, now, since the coming of Christ, live together with them and pray for our enemies, and try to persuade those who hate us unjustly to live conformably to the good precepts of Christ, that they may share the same joyful hope as ourselves.”

— Justin Martyr, Apology 1.14 (c. AD 155)

On the Mission of Christ

“Christ was not sent forth for the rich or the mighty, but for the poor and the humble.

He chose unlearned men to be His disciples, that thus there might be no pretense of human wisdom.

For through the power of God they proclaimed to every race of men that they were sent by Christ to teach all the Word of God.”

— Justin Martyr, Apology 1.39 (c. AD 155)

On the Eucharist

“We do not receive these as common bread and common drink; but as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word … is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.”

— Justin Martyr, Apology 1.66 (c. AD 155)

On Christian Worship and the Lord’s Day

“And on the day called Sunday all who live in the cities or in the country gather together in one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits.

When the reader has finished, the president verbally instructs and exhorts to the imitation of these good things.Then we all rise together and offer prayers, and, as we said before, when we have finished the prayer, bread and wine and water are brought, and the president likewise offers prayers and thanksgivings, according to his ability, and the people assent, saying, Amen.

There is a distribution to each, and a participation of that over which thanks have been given; and to those who are absent a portion is sent by the deacons.

Those who are well to do and willing give what each thinks fit, and what is collected is deposited with the president, who succors the orphans and widows and those who, through sickness or any other cause, are in want, and those who are in bonds, and the strangers sojourning among us—in a word, he takes care of all who are in need.But Sunday is the day on which we all hold our common assembly, because it is the first day on which God, having wrought a change in the darkness and matter, made the world; and Jesus Christ our Saviour on the same day rose from the dead.”

— Justin Martyr, Apology 1.67 (c. AD 155)

Key Insights

- Justin presents Christianity as the rational faith of the Logos—reason fulfilled in divine revelation.

- His introduction reveals the courage of a believer appealing directly to an emperor for justice rather than privilege.

- He demonstrates that faith transforms society: from lust to purity, from greed to generosity, from hate to love.

- His account of Sunday worship provides the earliest written outline of the Christian liturgy — Scripture reading, teaching, prayer, communion, and offerings for the poor.

- His theology of Christ’s humility and the Eucharist reveals a faith both spiritual and incarnational — rooted in history yet directed toward eternity.

- Justin’s Apology helped shape how the empire, and later the world, would understand the moral and intellectual integrity of Christianity.

Melito of Sardis (c. AD 160 – 170, to Antoninus Pius)

Melito, bishop of Sardis in Asia Minor, was one of the most eloquent and poetic voices of the second century.

He wrote prolifically—biblical commentaries, treatises on the incarnation, and one of the earliest Christian apologetic petitions addressed to Emperor Antoninus Pius.

A lifelong student of Scripture and Greek philosophy, Melito combined rigorous theology with literary power.

His writings, though only partly preserved, reveal a church confident, reflective, and spiritually mature in the decades following Hadrian’s persecutions.

From the Apology to Antoninus Pius

“Our faith, which men call a philosophy, first arose among peoples outside your civilization—among the ancient Hebrews.

But having spread into your dominions during the great reign of Augustus, it has become a source of blessing and peace.

From that time to your own reign, O Emperor, it has suffered nothing evil; rather, it has shone brightly under emperors who love justice.”

— Melito of Sardis, Apology to Antoninus Pius (fragment in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 4.26.7, c. AD 160)

Melito’s opening line means that Christianity, though born from Israel’s faith outside the Greco-Roman world, entered the empire under Augustus and brought moral good rather than harm.

He honors Antoninus as the latest in a line of “pious emperors” who have allowed this faith to flourish within Rome’s peace.

From the Passover Homily (Peri Pascha)

Preached around AD 160, Melito’s On the Pascha interprets the Jewish Passover as the prophetic shadow of Christ’s crucifixion.

No early writer expresses so vividly the church’s conviction that redemption fulfills the story of Israel.

“This is He who made the heavens and the earth,

and in the beginning created man;

who was proclaimed through the law and the prophets;

who became human through the Virgin;

who was hanged upon the tree;

who was buried in the earth;

who rose from the dead;

who ascended into the heights of heaven;

who sits at the right hand of the Father;

who has the power to save all things,

through whom the Father made all things

from the beginning of the world to the end of the age.”

— Melito of Sardis, On the Pascha 68–69

“He that hung the earth in space is Himself hanged;

He that fixed the heavens in place is fixed with nails;

He that supports the earth is supported upon a tree;

the Master has been outraged;

God has been murdered.

He is lifted up upon a tree, and the earth trembles;

He has died, and creation is shaken.

He has gone down into Hades, and He has raised the dead.”

— Melito of Sardis, On the Pascha 96–100

“He is the Lamb slain; He is the silent Lamb;

He is the one born of Mary, the fair ewe-lamb;

He was taken from the flock, and led to slaughter, and at evening slain;

He was buried at night;

by day He rose again.”

— Melito of Sardis, On the Pascha 105–106

Melito turns suffering into triumph: the cross becomes the world’s true Passover — deliverance not from Egypt, but from sin and death.

Key Insights

- Melito embodies the maturing Christian mind of the second century: biblically grounded, philosophically articulate, and artistically profound.

- His Apology shows Christianity as compatible with the empire’s peace; his Passover Homily reveals the soul of Christian worship — a theology of deliverance through sacrifice.

- By linking the story of Israel to the suffering of Christ, he gives language to the church’s sense of continuity and fulfillment.

- His poetry closes this age of apologists on a note of triumph: the same empire that crucified Christ now carries His gospel to the nations.

Conclusion — What We Learn from the Apologists

Antoninus Pius ruled during what later generations called a “reign of peace,” yet the very existence of these Apologies proves that peace was fragile.

Christians were still mistrusted, accused, and sometimes condemned simply for bearing the name of Christ.

There was no imperial campaign against them, but the law itself still made them criminals in principle.

These writings—by Quadratus, Aristides, Justin, and Melito—are therefore appeals for justice in a world that granted none, letters from men who lived in peace only by the patience of their persecutors.

Yet in this tension we see something extraordinary.

Instead of withdrawing in fear or responding in anger, the church of the second century answered misunderstanding with explanation, hostility with holiness, and suspicion with love.

Their pens became their defense; their lives became their argument.

Themes and Insights to Note

1. The Legal and Social Reality

- “Peace” under Antoninus Pius meant the absence of official persecution, not true liberty.

- The Apologists write as citizens appealing to reason, asking the emperor to judge Christians by deeds, not rumors.

- Their tone is respectful yet confident: they believe truth can withstand investigation.

2. The Picture of Christian Life

- Aristides describes a people marked by chastity, honesty, hospitality, and compassion:

“They love one another… they rescue the orphan… they fast two or three days that they may feed the needy.” - Justin shows a transformed community: former pagans now living in purity, generosity, and reconciliation.

- This moral beauty was not secondary to their faith—it was their primary evidence that the gospel was true.

3. The Picture of Christian Worship

- From Justin’s detailed account we learn the pattern of early gatherings: Scripture reading, exhortation, prayer, the Eucharist, and offerings for the poor.

- Worship was simple but profound—anchored in memory of the risen Christ and in service to the needy.

- Charity was liturgy; compassion was worship.

4. The Intellectual and Spiritual Emphasis

- Quadratus grounded faith in eyewitness history.

- Barnabas re-interpreted the covenant spiritually, showing fulfillment, not rejection, of Israel’s story.

- Aristides demonstrated that Christian virtue surpasses pagan philosophy.

- Justin joined faith with reason and made moral transformation the church’s strongest argument.

- Melito lifted theology into poetry, proclaiming the cross as the true Passover and the world’s redemption.

5. The Continuing Relevance

- These writers do more than defend—they define what Christianity is.

- Their emphasis on holiness, community, and service remains the church’s enduring witness.

- Their courage under a veneer of peace reminds us that faithfulness does not depend on favorable conditions but on steadfast conviction.