When Emperor Gaius Messius Quintus Decius came to power in AD 249, the Roman Empire was unraveling.

The northern frontiers were collapsing under Gothic pressure.

Civil wars and mutinies had stripped away the sense of divine favor that had long sustained Roman identity.

The economy, ravaged by inflation and plague, staggered beneath decades of crisis.

Decius—an old-fashioned senator from Pannonia—believed that the solution was not merely political or military but spiritual.

He declared that Rome’s troubles stemmed from the neglect of its ancestral gods.

To save the empire, he would restore the ancient religion, the sacrificia publica that had once bound the provinces to the gods of Rome.

He dreamed of a unified empire where all citizens once again poured libations to Jupiter, Juno, and Mars—just as Augustus had revived the temples three centuries earlier.

To Decius, it was not persecution but piety.

To Christians, it was the empire’s first universal test of faith.

1. Rome’s Imperial Revival of Piety

Later Roman historians remembered Decius as a reformer, not a persecutor.

Aurelius Victor recorded:

“Decius wished to restore the ancient discipline and the ceremonies of the Romans, which for a long time had fallen into neglect.”

(De Caesaribus 29.1, c. AD 360)

The Chronographer of 354, a Roman calendar and imperial chronicle compiled under Constantius II from earlier state records, likewise notes:

“Under Decius, sacrifices were ordered throughout the provinces, that all might offer to the gods.”

(Chronographus Anni CCCLIIII, Part XII ‘Liber Generationis’, AD 354)

Decian coinage confirms this campaign of religious restoration. Thousands of coins survive showing the emperor pouring a libation at an altar, with legends such as PIETAS AVGG (“The Piety of the Emperors”) and GENIVS SENATVS.

The latter inscription—GENIVS SENATVS—invoked the “Genius of the Senate,” the divine spirit believed to guard and embody the Roman Senate itself.

Every household, legion, and civic body in Rome was thought to possess its own genius, a protective deity who received offerings of wine and incense.

By reviving the Genius Senatus cult, Decius was sacralizing the institutions of Rome themselves—binding political loyalty and divine worship into one act.

These coins, struck in Rome, Antioch, and Viminacium, visually proclaimed that the restoration of the gods meant the restoration of the state.

| Side | Inscription (Latin) | Expanded Form | Translation (English) | Description / Symbolism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse (Front) | IMP C M Q TRA DECIVS AVG | Imperator Caesar Marcus Quintus Traianus Decius Augustus | “Emperor Caesar Marcus Quintus Trajan Decius Augustus” | Laureate, draped, and cuirassed bust of Decius facing right. The adoption of the name Trajan links him with Rome’s most admired emperor, emphasizing his mission to restore Roman discipline and piety. |

| Reverse (Back) | VICTORIA AVG | Victoria Augusti | “Victory of the Emperor” | Depicts Victory (Nike) standing left, presenting a wreath to the Emperor Decius, who stands facing her, holding a spear. The wreath symbolizes triumph and divine approval. The scene celebrates Decius’s military success and divine sanction for his rule. |

Every coin and inscription declared that the gods were returning—and every Christian knew what that would soon mean.

2. The Edict and the Libelli Certificates

In January AD 250, Decius issued an edict commanding all inhabitants of the empire to perform public sacrifice before local officials and obtain written proof of obedience.

Those who refused faced imprisonment or death.

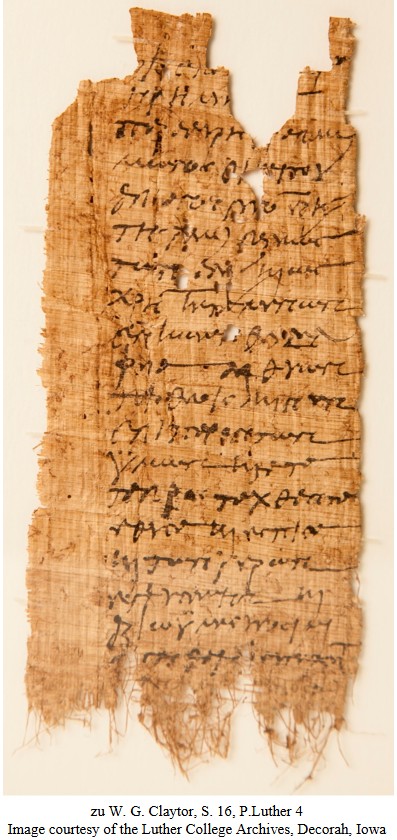

Dozens of papyri discovered in Egypt record the edict’s enforcement. The best-known, now in the Oxford Bodleian Library, reads:

“To the commissioners of sacrifices of the village of Alexander’s Island, from Aurelia Ammonous, daughter of Mystus, aged forty years, scar on right eyebrow. I have always sacrificed to the gods, and now in your presence, in accordance with the edict, I have sacrificed and poured a libation and tasted the offerings. I request you to certify this below. Farewell.”

(Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 2601, AD 250)

Other libelli from Fayum and Theadelphia bear identical phrasing—kata to prostagma (“according to the edict”)—and carry the red-ink seals of village commissioners.

These fragile papyri, recovered by archaeologists in the 1890s, are the only surviving documents produced in direct obedience to Decius’s decree.

They prove that the policy was systematic and bureaucratic—Rome’s paper war against conscience.

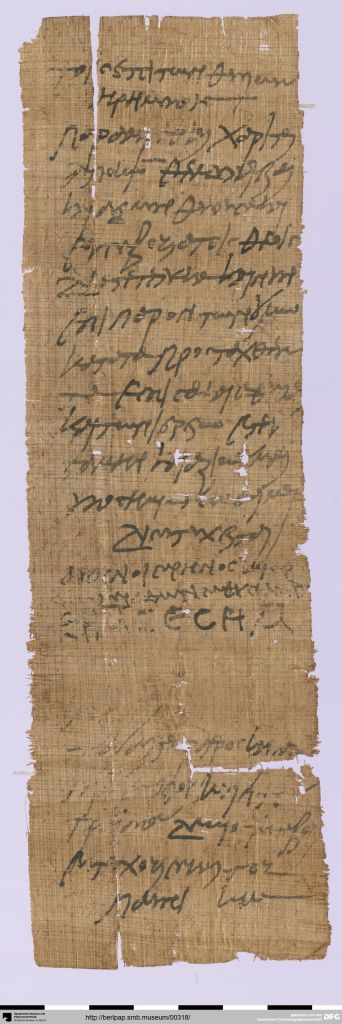

“To those who have been selected to oversee the sacrifices, from Aurelius Sarapammon, servant of Appianus, former exegetes of the most-illustrious city of the Alexandrians, and however he is styled, residing in the village of Theadelphia. Always sacrificing to the gods, now too, in your presence, in accordance with the orders, I sacrificed and poured the libations and tasted the offerings, and I ask that you sign below. Farewell. (2nd hand) We, the Aurelii Serenus and Hermas, saw you sacrificing (?) …”

“To the commissioners of sacrifices of the village of Theadelphia:

From Aurelius Syrus, the son of Theodorus, of the village of Theadelphia. I have always sacrificed to the gods, and now, in your presence, I have poured libations, sacrificed, and tasted the sacred offerings, according to the edict. I ask you to certify this for me. Farewell.

We, Aurelius Serenus and Aurelius Hermas, have seen you sacrificing.

Year 1 of the Emperor Decius (AD 250).”

3. The Policy in Motion: Fear and Defiance

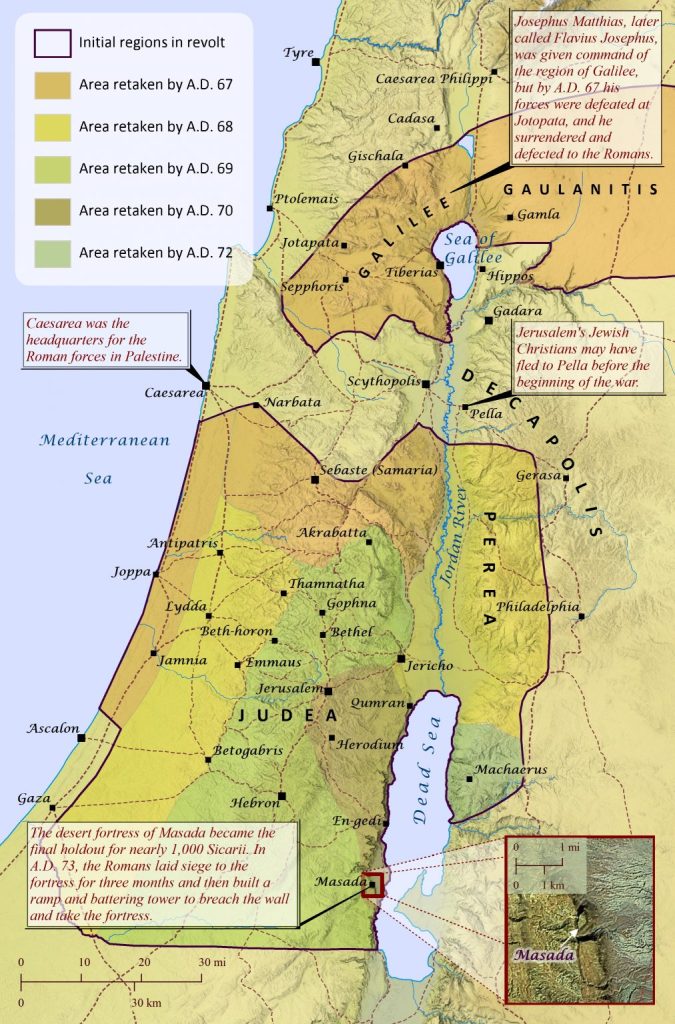

Governors such as Sabinus in Egypt and Urbanus in Palestine carried out the edict with zeal.

Eusebius of Caesarea later wrote:

“Decius, who became emperor after Philip, was the first to raise a universal persecution against the Church throughout the inhabited world. There was great persecution against us; the governor Urbanus displayed great zeal in carrying out the imperial commands. Some of the faithful were dragged to the temples and forced to offer sacrifice by tortures.”

(Ecclesiastical History 6.39.1; 6.41.10–12, c. AD 310–325)

Even pagan dedications record the campaign: a marble inscription from Thasos honors local magistrates “for restoring the sacrifices that had fallen into neglect.”

For Decius these were civic triumphs; for Christians, they were death warrants.

4. Voices from the Fire: Martyrdom Across the Empire

Alexandria – Apollonia and the First Flames (AD 249–250)

Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria, an eyewitness, reported:

“The old virgin Apollonia was seized, her teeth broken out, and fire prepared. They threatened to burn her alive if she refused to repeat impious words. She leapt of her own accord into the fire and was consumed.”

(Letter to Fabius of Antioch, in Eusebius 6.41.7–8)

“All Egypt was filled with the noise of those who called upon Christ even in the midst of their tortures.”

(ibid. 6.41.13)

Archaeology corroborates his words: Egyptian sites at Bacchias and Oxyrhynchus reveal temples hastily refurbished and new altars installed in strata dated precisely to AD 250—evidence of an empire suddenly compelled to sacrifice.

Smyrna – Pionius and Companions (AD 250)

The Martyrdom of Pionius preserves an authentic courtroom record:

“On the day of the feast of Saint Polycarp, while we were fasting, the chief of police came suddenly upon us with men bearing chains and bade us sacrifice to the gods. And Pionius said, ‘We are Christians; it is not lawful for us to sacrifice to idols.’”

(Martyrdom of Pionius 2–3)

“They hung him by his wrists, fixing his feet in the stocks. He said, ‘You mistake my torment for your victory; yet it is my freedom, for I rejoice to suffer for the name of Christ.’”

(ibid. 20)

“He breathed out his spirit, and a sweet odor, as of incense, filled the air.”

(ibid. 21)

In Smyrna’s agora, archaeologists have identified a mid-third-century inscription honoring the local strategos who “maintained the sacrifices.” It almost certainly relates to this same enforcement.

Rome – Fabian, Bishop and Martyr (January AD 250)

“Fabian, the bishop of the city of Rome, suffered martyrdom under Decius.”

(Eusebius 6.39.5)

The Depositio Martyrum adds:

“On the twentieth day of January, Fabian, bishop, in the Catacombs.”

His epitaph—FABIAN EPISCOPVS MARTYR—was found in the Catacomb of Callistus.

Soot stains from vigil lamps still darken the marble, showing that Christians visited the site immediately after his death to honor their bishop.

Antioch – Babylas, The Bishop in Chains (AD 250)

“At Antioch, Babylas, bishop of the church there, after glorious bonds and confession, fell asleep in prison.”

(Eusebius 6.39.4)

Archaeological excavations north of Antioch have uncovered the Basilica of Babylas, built atop a repurposed Roman cemetery. Beneath its altar lay a third-century sarcophagus scratched with crosses—widely accepted as the resting place of the Decian bishop who died in chains.

Carthage – Mappalicus and the Imprisoned Confessors (AD 250)

Cyprian wrote from exile:

“Blessed Mappalicus, glorious in his fight, gave witness before the proconsul that he would soon see his Judge in heaven. And when the day came, he was crowned with martyrdom, together with those who stood firm with him.”

(Epistle 37.3)

“The prison has become a church; their bonds are ornaments, their wounds are crowns.”

(Epistle 10.2)

Archaeologists excavating beneath the later Cyprianic Basilica in Carthage found reused Roman blocks incised in red with the names MAPPALICUS VICTOR and FELIX CONFESSOR, strong evidence of a local memorial tradition dating directly to Decius’s time.

Macedonia – Maximus and Companions (AD 250–251)

“In Macedonia, the blessed Maximus and many others gave proof of their faith, being scourged and stoned and finally beheaded.”

(Eusebius 6.43.4–5)

Provincial coinage from Thessalonica of AD 250–251 depicts the goddess Roma receiving sacrifice—a local mirror of the imperial policy that cost these believers their lives.

Sicily – Agatha of Catania (AD 250)

“Quintianus commanded that her breasts be torn with iron hooks, but she said, ‘These torments are my delight, for I have Christ in my heart.’”

(Passio Agathae 6, 3rd-century nucleus)

In Catania’s cathedral crypt, a mid-third-century inscription reading AGATHAE SANCTAE MARTYRI was found in situ, demonstrating that her cult was already established within a generation of her death.

5. The Problem of the Lapsed

Many believers succumbed to fear and sacrificed or bought forged libelli. The Church now had to decide: could such people be restored?

Cyprian’s Pastoral Balance

“Neither do we prejudice God’s mercy, who has promised pardon to the penitent, nor yet do we relax the discipline of the Gospel, which commands confession even unto death.”

(Epistle 55.21, AD 251)

“Let everyone who has been wounded by the devil’s darts, and has fallen in battle, not despair. Let him take up arms again and fight bravely, since he still has a Father and Lord to whom he may return.”

(On the Lapsed 36, AD 251)

Novatian’s Rigorism and Schism

“He who has once denied Christ can never again confess Him; he has denied Him once for all.”

(De Trinitate 29, mid-3rd century)

Bishop Cornelius countered:

“Novatian has separated himself from the Church for which Christ suffered. He says the Church can forgive no sin; yet he himself sins more grievously by dividing the brethren.”

(Eusebius 6.43.10–11)

Fragments of Cornelius’s own epitaph—CORNELIVS EPISCOPVS MARTYR—found near the Callistus catacombs show how quickly the debate over mercy was itself hallowed in stone beside the graves of Decian victims.

Dionysius of Alexandria’s Moderation

“Some of the confessors, being too tender-hearted, desired to welcome all indiscriminately, but we persuaded them to discern, that mercy is good when it is tempered with justice.”

(Eusebius 6.42.4–5)

“Each church dealt with the fallen as it judged best, some treating them harshly, others gently. In this diversity of discipline, yet unity of faith, the Lord was glorified.”

(ibid. 6.42.6*)

6. Pagan Reflection and Christian Memory

Lactantius explained the emperor’s motives:

“Decius, being a man of old-fashioned rigor, desired to restore the ancient religion; and therefore he decreed that sacrifices should be offered to the gods by all. He did evil while intending good.”

(Divine Institutes 5.11, c. AD 310)

Eusebius reflected:

“Those who endured were tried as by fire and found faithful; others, weak through fear, failed the test, yet afterward were restored through tears and repentance.”

(Ecclesiastical History 6.42.2)

Roman catacomb graffiti from this very decade—FELIX MARTYR IN PACE and VICTOR IN CHRISTO—show that Christians carved into the walls the same theology Eusebius would later write: faith tested by fire, rewarded with peace.

7. The End and the Legacy

In AD 251, Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus fell in battle against the Goths near Abrittus. The edict died with them.

But its memory lived on in papyrus and stone—libelli in the desert, epitaphs beneath Rome, and basilicas raised over tombs from Antioch to Carthage.

The Decian persecution produced the earliest empire-wide martyrology, the first letters written from prison, and a theology forged in fire.

It made public what Rome could never suppress:

“We must obey God rather than men.” — Acts 5:29

The empire had demanded a certificate; the Church answered with a confession.