In the earliest centuries, Christianity was not first met with philosophical argument or careful analysis. It was mocked. Before the treatises of Celsus or Porphyry, the first criticisms were graffiti, slanders, and satire. These sneers are important because, even in ridicule, they confirm what outsiders saw in Christians — especially that Christians openly worshiped Christ as God.

Josephus and the Donkey-Head Libel (c. AD 93–95)

The Egyptian writer Apion accused the Jews of worshiping a donkey. Josephus, writing under Domitian around AD 93–95, preserved this insult in Against Apion so he could expose its absurdity.

“Apion, however, was bold enough to foist upon us a most shameless calumny about our temple, alleging that the Jews kept in it the head of an ass, an object of worship, and that the priests of the temple used to swear oaths by it. To support this, he pretended that, when Antiochus Epiphanes entered the sanctuary and carried off the treasures, he discovered the head of an ass made of gold and worth a great deal of money.” (Against Apion 2.80, Loeb)

Josephus ridicules the idea:

“This is a most ridiculous invention, for how could any man who had once entered the temple and looked at its construction and fittings have accepted such a lie, or how could any person who knew the temple rites and customs have believed it? For Apion was an Egyptian, and it is the height of impudence for a man who worships dogs and monkeys and goats to reproach us for allegedly reverencing asses.” (Against Apion 2.81, Loeb)

He then appeals to history itself, noting that when Antiochus plundered the temple he found only vessels of gold, never any idols:

“In fact, when Antiochus entered the sanctuary and found no representation of animals at all, but only bare walls, pillars, and a lampstand of gold and a table and libation vessels, and all the offerings required by the law, he carried them off.” (Against Apion 2.82–83, Loeb)

Key insights:

- The donkey-head charge began as anti-Jewish propaganda, but because Romans often confused Jews and Christians, it easily transferred to Christians.

- Josephus’s detailed rebuttal shows this accusation was well known across the empire, serious enough to require public correction.

- This slander would not disappear. In time, it resurfaced in the Alexamenos graffito and in later accusations against Christians themselves.

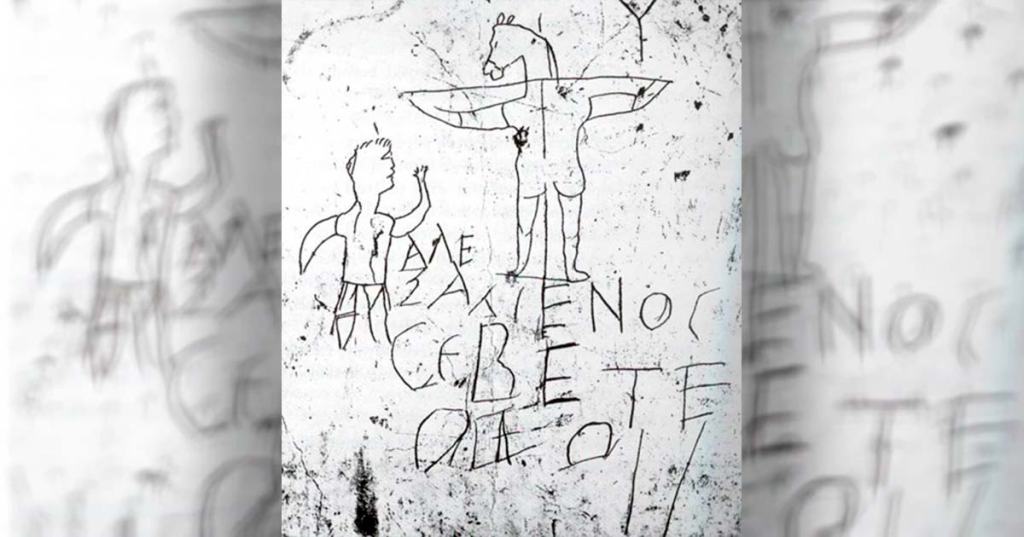

The Alexamenos Graffito (late 1st–3rd century AD, Palatine Hill, Rome)

Scratched into the plaster wall of a building on the Palatine Hill in Rome, directly connected with the imperial palace, is the earliest surviving caricature of Christian worship. The structure is usually called the Paedagogium because it may have housed imperial page boys — though some scholars think it functioned as barracks or service quarters. Whatever its exact purpose, it was part of daily life around the emperor’s residence.

The graffito, dated between the late first and third centuries, depicts a man with hands raised in prayer before a crucified figure with a donkey’s head. Beneath it is scrawled:

“Alexamenos worships his god.”

Key insights:

- This combines the old donkey libel with the shame of the cross — a double insult.

- But its testimony is even more valuable: it confirms that Christians were recognized not just as followers of a teacher but as people who worshiped Christ as God. The figure of Alexamenos is not admiring Jesus’ teachings — he is worshiping.

- Outsiders mocked the absurdity of worshiping someone crucified, but in their laughter they preserved one of the most important truths: by the late 1st or early 2nd century, Jesus was already the object of divine worship among Christians.

Lucian of Samosata and The Passing of Peregrinus (c. AD 165–170)

By the mid-2nd century, Christianity was visible enough that it caught the attention of professional satirists. Lucian of Samosata (c. 120–after 180), a Syrian writing in polished Greek, made a career out of ridiculing philosophers, cults, and public figures.

In The Passing of Peregrinus, Lucian lampoons a Cynic philosopher who briefly associated with Christians before turning to Cynicism and later burning himself to death at the Olympic Games. In mocking Peregrinus, Lucian gives us one of the most vivid pagan portraits of Christianity in his own day.

Peregrinus Among the Christians (§11)

“It was then that he [Peregrinus] learned the wondrous lore of the Christians, by associating with their priests and scribes in Palestine. And — how else? — in short order he made them all look like children, for he was prophet, cult-leader, head of the synagogue, and everything, all by himself. They spoke of him as a god, accepted him as a lawgiver, and made him their leader, and took him for a prophet, next after that one whom they still worship, the man who was crucified in Palestine because he introduced this new cult into the world. They were all incredibly attentive to him; he interpreted and explained their books, and wrote many of his own, and they revered him as a lawgiver, a master, and a great man.” (Peregrinus 11, Loeb)

Key insights:

- The story begins in Palestine. Lucian uses synagogue terms — “priests,” “scribes,” “head of the synagogue” — which Christians themselves did not use in this period. This shows either that Jewish-Christian congregations still retained synagogue-like terminology, or that Lucian, as an outsider, simply described them using Jewish categories he understood. Either way, it reflects the ongoing Jewish roots of Christianity in Palestine.

- Lucian sneers that Peregrinus made Christians “look like children,” ridiculing them as gullible. But notice the force of his complaint: Christians were a people who listened to teachers, honored leaders, and gave them space to explain the Scriptures.

- The heart of the satire comes in the line: “They spoke of him as a god, accepted him as a lawgiver, and made him their leader, and took him for a prophet.” Lucian laughs at their naïve devotion, but the passage shows how seriously Christians took spiritual leadership.

- Yet he adds the crucial qualification: Peregrinus was only “next after that one whom they still worship.” This is powerful. Even in ridicule, Lucian confirms that Jesus was worshiped as God — not simply admired as a wise teacher.

- Lucian says Peregrinus “interpreted and explained their books.” This is an outsider’s confirmation that Christians had authoritative Scriptures by AD 165, which were read aloud and taught in their assemblies.

Christian Support from Asia Minor (§12)

“Indeed, people came even from the cities of Asia, sent by the Christians at their common expense, to help and defend and encourage the hero. They show incredible speed whenever anything of this sort is undertaken publicly; for in no time they lavish their all. So it was then too: the venerable Peregrinus was in want of nothing, all these things being provided in abundance. Certain of their officials, called presbyters and readers, came from the province, bringing him letters and presenting him with gifts and money. And much was said then also of his dignity and of his extraordinary influence among the Christians.” (Peregrinus 12, Loeb)

Key insights:

- The geography now shifts to Asia Minor (modern Turkey), the powerhouse of Gentile Christianity. Here the terminology changes: Lucian refers not to “priests and scribes” but to presbyters (elders) and readers (lectors) — technical titles that match what we find in Christian sources. This shows the diversity of Christian leadership structures across regions.

- Christians supported Peregrinus “at their common expense.” This reveals communal, organized giving: congregations across cities pooled resources as one body.

- The striking phrase, “for in no time they lavish their all,” is one of the clearest pagan testimonies to Christian generosity. Lucian is mocking, but his words confirm that Christians were known for urgency and sacrificial giving. They did not hesitate; they poured out resources quickly, as though generosity was their reflex.

- Peregrinus “was in want of nothing.” This confirms the effectiveness of Christian charity. Outsiders may have laughed at their eagerness, but they could not deny that Christians took care of their own.

- By mentioning presbyters and readers, Lucian accidentally shows us that by the mid-2nd century, Christian churches already had structured leadership and liturgical offices.

- He notes Peregrinus’s “extraordinary influence.” To Lucian, this made Christians gullible; to us, it shows their deep loyalty and respect for leaders who taught the Scriptures faithfully.

Lucian’s General Description of Christians (§13)

“The poor wretches have convinced themselves, first and foremost, that they are immortal and will live forever. Therefore they despise death, and many of them willingly give themselves up. And then their first lawgiver persuaded them that they are all brothers, the moment that they transgress and deny the Greek gods and begin worshiping that crucified sophist and living by his laws. So they despise all things equally and regard them as common property. And without any clear evidence they receive such doctrines on faith alone. And when once this has been done, they think themselves secure for all eternity. Accordingly, if any charlatan and trickster, able to profit by occasions, comes among them, he soon acquires sudden wealth by imposing upon simple folk.” (Peregrinus 13, Loeb)

Key insights:

- Lucian now speaks not about Peregrinus but about Christians as a whole. This is his general description of the movement.

- He says they “despise death, and many of them willingly give themselves up.” This is crucial evidence. It shows that by AD 165 Christians across the empire were famous for their courage in persecution and their willingness to face execution rather than renounce their Lord. It confirms the ongoing empire-wide legal standard: since Trajan’s policy (AD 112), Christians could be executed anywhere if accused and refusing to sacrifice. Lucian’s words confirm both the policy and the Christians’ reputation for meeting it with fearless resolve.

- He mocks their brotherhood: “they are all brothers.” Yet this testifies to their radical equality, where social divisions of class, ethnicity, and gender were dissolved in Christ.

- He sneers, “they regard all things as common property.” To him, it was foolishness. But this is one of the most important pagan confirmations that the communal life of Acts 2–4 — “they had all things in common” — was still being practiced more than a century later. Outsiders still saw Christians as people who shared freely with one another.

- The sharpest ridicule comes when he says, “without any clear evidence they receive such doctrines on faith alone.” This points directly at the heart of Christianity: belief in realities that could not be demonstrated by philosophy — the resurrection of Christ, his divinity, and heaven itself. To Lucian, this was gullibility; to Christians, this was faith.

- He continues, “they think themselves secure for all eternity.” What he mocks as arrogance is one of the most precious features of early Christianity: the assurance of salvation. Christians lived with confidence that eternal life was guaranteed through Christ.

- Finally, he says tricksters could profit among them. This confirms their openness and inclusivity. They welcomed outsiders generously, sometimes at the risk of being deceived.

The Prison Scene (§§16–17)

“For after he [Peregrinus] had been apprehended on a charge, which I need not dwell on, he was put in prison. Then it was that he was much in the public eye; and then it was that the Christians, regarding the incident as a disaster for themselves, left nothing undone to rescue him. Then was seen the extraordinary zeal of these people in all that concerns their community; and they showed incredible speed whenever anything of the kind occurred. From the very break of day aged widows and orphan children might be seen waiting about the prison; and their leading men even bribed the guards, and slept inside with him. Then elaborate meals were brought in; and their sacred writings were read aloud; and Peregrinus was called a new Socrates by them. Then there was actually talk of trying to procure his release from the authorities, though this did not succeed. After this, when he had been freed, he again transgressed and was excommunicated from their community.” (Peregrinus 16–17, Loeb)

Key insights:

- Christians regarded Peregrinus’s imprisonment as “a disaster for themselves.” This shows their communal identity: when one member suffered, the whole body felt the pain.

- Lucian notes their “extraordinary zeal” and “incredible speed.” Again, Christians are portrayed as people who acted immediately and sacrificially in response to persecution.

- From dawn, widows and orphans gathered outside the prison. The most vulnerable members were visibly part of the Christian movement, and they joined the community in solidarity with the suffering.

- “Leading men” bribed guards and even slept inside with Peregrinus. Outsiders laughed at this as naïve, but it reveals Christians’ willingness to risk money, safety, and exposure to protect one another under the empire’s hostile laws.

- They brought elaborate meals and read aloud from their Scriptures. This detail is striking: even in prison, Christian life revolved around fellowship and the Word. This matches what we see in the New Testament (1 Tim. 4:13) and in Justin Martyr’s description of worship (c. 155), where the Scriptures were always read aloud. Lucian’s sneer confirms this practice was well known.

- He says they called Peregrinus a “new Socrates.” He exaggerates, but the comparison shows how Christian martyrdom was framed — even by outsiders — as akin to the noble deaths of philosophers who died for truth.

- Finally, Lucian says Peregrinus was later excommunicated. This confirms that Christians were not endlessly gullible; they had boundaries and mechanisms of discipline to protect their unity.

Conclusion: Mockery that Confirms

From Josephus’s donkey libel (AD 93–95), to the Alexamenos graffito in Rome (late 1st–3rd century), to Lucian’s satire (AD 165–170), we see how Christianity appeared to its earliest critics.

- They mocked Christians for worshiping Christ as God — especially a crucified man.

- They sneered at their brotherhood and radical sharing of goods.

- They ridiculed their faith without proof and their assurance of salvation.

- They derided their generosity and openness as gullibility.

- And above all, they laughed at their willingness to face death.

Yet in trying to humiliate them, these critics have given us one of the clearest portraits of the early church: a people marked by Scripture, brotherhood, generosity, courage, and worship of Christ. The very things their enemies thought laughable were the very things that gave the church its strength.