1. How Historians Work

Every historian begins with a simple task: to determine what most probably happened.

We cannot replay the past; we weigh evidence, compare sources, and choose the explanation that best fits the facts.

When we study Christianity’s beginnings, we apply the same discipline.

We ask: Given what we know from documents, archaeology, and human behavior, what is the most probable explanation for the events those first witnesses described?

And that leads to the hardest question of all—can the most probable explanation ever be a miracle?

2. Can a Miracle Ever Be the Most Probable Explanation?

Historians examine what is ordinary and repeatable; miracles and visions claim what is extraordinary and unique.

If we rule them out before hearing the evidence, our conclusions are fixed in advance.

If we leave the door open, we must ask what kind of testimony could ever justify believing that the impossible happened.

Christianity rests entirely on one such claim: that Jesus of Nazareth, executed under Pontius Pilate, was seen alive again.

Whether those appearances were real or imagined decides the truth of the entire faith.

3. Why Philosophical Arguments Are Not Enough

1. Atheists often win the philosophical debate.

- Classical proofs for God—design, fine-tuning, first cause—sound persuasive until we look closely at the data.

- The fine-tuning argument claims that the constants of nature are so precise that life could not exist unless a Creator adjusted them perfectly.

- But the same evidence can be read the opposite way: in a universe that may contain two hundred billion galaxies and perhaps countless more beyond, chance had nearly infinite opportunities to assemble one planet with the right conditions.

- Earth could simply be the lucky combination—the one world where chemistry and time happened to produce life.

- The rest of the cosmos is vast and lifeless; we have found no sign of life anywhere else.

- What we actually observe is not elegant or symmetrical design but a messy, wasteful, and violent process: stars explode, galaxies collide, and most of space is deadly to life.

- The universe looks more random than purposeful—beautiful in places, but mostly silent and cold.

2. Human experience looks unfair.

- Even here on the one world that sustains life, chance seems to rule.

- The wicked often prosper; the good and innocent suffer.

- If a good and all-powerful God directs everything, why does He allow that?

- This question—the problem of suffering—is what turned Bart Ehrman from faith to atheism.

3. Christianity begins somewhere else—an event, not an idea.

- The first Christians did not try to prove God by philosophy or science.

- They proclaimed a moment in history: the resurrection of a crucified man.

- No one would have invented that story.

- We would have placed it earlier in history so more people could see it.

- We would not have made a tortured, executed criminal the center of faith.

- Yet that is exactly what happened.

4. Without that event, Christianity does not exist.

- The resurrection, if real, explains why the movement began at all.

- If false, the philosophical arguments for God would have faded long ago.

- The faith of billions rests on something that should never have been imagined—unless it was true.

5. Paul himself recognized how implausible it sounds.

“We preach Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, but to those who are called, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God.” — 1 Corinthians 1:23–24

The earliest missionary of the faith admitted that the message defied both Jewish expectation and Greek philosophy.

Christianity began not because it made sense, but because the impossible appeared to have happened.

4. David Hume and the Historian’s Dilemma

In 1748 the Scottish philosopher David Hume gave the modern world its rule of doubt.

In An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, Section X, he wrote:

“A wise man … proportions his belief to the evidence. A miracle … is a violation of the laws of nature; and as a firm and unalterable experience has established these laws, the proof against a miracle … is as strong as any argument from experience can be.”

When Hume spoke of the laws of nature, he meant what human experience tells us always happens.

We call something a law because it never seems to fail—but what counts as ordinary depends entirely on experience.

If we paused to think about it, gravity itself would feel miraculous.

Right now the planet beneath our feet is spinning at about 1,000 miles per hour at the equator and racing around the Sun at roughly 67,000 miles per hour—while our entire Solar System hurtles around the super-massive black hole at the center of the Milky Way at nearly 490,000 miles per hour.

Yet none of us is flung into space. The air moves with the Earth, the oceans stay bound to it, and we walk steadily across a surface moving faster than a bullet.

We do not call this a miracle only because it happens to everyone all the time.

If a single person in the ancient world had experienced that invisible pull while the rest of humanity floated away, it would have been recorded as a divine wonder.

Regularity turns the wondrous into the expected.

That is what Hume meant by a law of nature—uniform experience.

But defining miracles as violations of uniform experience assumes that no new kind of experience could ever occur.

The question Christianity raises is whether an event could happen once in history—seen by real witnesses—and still be true even though it never happened again.

Hume continued:

“When anyone tells me, that he saw a dead man restored to life, I immediately consider with myself, whether it be more probable that this person should either deceive or be deceived, or that the fact, which he relates, should really have happened. … I always reject the greater miracle. If the falsehood of his testimony would be more miraculous, than the event which he relates; then, and not till then, can he pretend to command my belief.”

And finally he added the clause most readers forget:

“No testimony is sufficient to establish a miracle, unless the testimony be of such a kind, that its falsehood would be more miraculous than the fact which it endeavors to establish.”

Together these three statements summarize Hume’s logic:

- Miracles are violations of nature and therefore highly improbable.

- Deception or error will almost always be more likely than miracle.

- Yet if the witnesses are so credible that their deceit would itself be a greater miracle, reason should believe them.

That final concession is the opening Hume left.

5. Bart Ehrman and the Modern Wall

Modern historians often repeat Hume’s first two points and omit the third.

Bart D. Ehrman writes in How Jesus Became God (2014):

“Historians, by the very nature of their craft, cannot show whether miracles happened. History can only establish what probably happened in the past. And miracles, by definition, are the least probable events.” (p. 229)

This is Hume’s argument restated—but without the door left ajar.

By defining “probable” as “natural,” the possibility of miracle is closed before the evidence is heard.

For Hume, belief might still be rational if testimony made the falsehood the greater miracle; for Ehrman, that option no longer exists.

Ehrman himself does not argue that the disciples fabricated the story.

He accepts that Peter, James (the brother of Jesus), and Paul were all convinced that they had seen Jesus alive again.

In his view, their experiences were psychologically real but mistaken—the result of sincere self-deception, not deliberate fraud.

He explains:

“There is no doubt in my mind that some of the disciples claimed to have seen Jesus alive after his death. This is what they believed. I don’t think they were lying. They truly believed it. But just because they believed it doesn’t mean that it really happened. People have visions of loved ones all the time after they have died.” — Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus Became God (2014), pp. 182–183

Ehrman therefore grants the sincerity of the witnesses but denies the event itself, choosing the “deception through misperception” explanation over fabrication.

6. Bayesian Probability and the Weight of Evidence

Only fifteen years after Hume, the English minister-mathematician Thomas Bayes (1702–1761) published posthumously the paper that gave the mathematics of evidence.

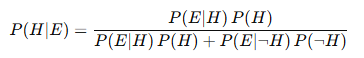

His formula, Bayes’s Theorem, shows how probability should be updated when new evidence appears:

The crucial term is the prior probability P(H)—our estimate before considering the evidence.

If that number is near zero, no amount of evidence will matter; if it is small but real, convincing testimony can dramatically change the outcome.

7. Atheist and Agnostic Philosophers Who Keep a Non-Zero Prior

Across the modern era, several non-theistic philosophers have recognized that a miracle may be improbable but not impossible.

They begin with a small yet real prior probability—roughly one to ten percent—that such an event could occur if the evidence were strong enough.

| Philosopher (date) | Viewpoint | Key Idea |

|---|---|---|

| Michael Scriven (1966) | Atheist philosopher of science | “It is a mistake to say that miracles cannot happen; the right claim is that no miracle has yet been shown to have happened.” |

| J. L. Mackie (1982) | Agnostic (Oxford) | “If we had a really impressive testimony from many sensible and independent witnesses, the balance of probability might tilt even for a miracle.” |

| Kai Nielsen (1989) | Atheist (Canada) | “The fact that something is unprecedented is not itself a decisive reason to reject it; unprecedented things sometimes happen.” |

| Antony Flew (1966 → 2007) | Atheist → Deist | Early: “Probability is always against miracles.” Later: “The laws of nature cannot rule out a God who can act within them.” |

| Michael Shermer (1997) | Atheist historian of science | “The more extraordinary the claim, the more extraordinary the evidence must be.” |

| Peter Millican (2003) | Agnostic (Hume scholar) | “Hume does not show that belief in miracles is irrational; only that it would require evidence of an order rarely, but not impossibly, met.” |

| Paul Draper (1989 → present) | Agnostic Bayesian philosopher | “A low prior probability can be overcome by very strong evidence.” |

| John Earman (2000) | Atheist philosopher of science | “Hume’s argument is an abject failure… sufficiently strong testimony can raise even a very improbable event to high probability.” |

| Julian Baggini (2003) | Atheist popular philosopher | “Atheists need not claim that miracles are impossible—only that no evidence yet meets the burden of proof.” |

Despite their differences, all admit what Hume’s disciples often deny: a miracle could be credible if the testimony were overwhelming.

8. The Outlier: Richard Carrier and the Closed Universe

The modern mythicist Richard Carrier uses Bayes’s Theorem but begins with what he calls an “extraordinarily low” prior for any miracle claim:

“I will assume the prior probability that any miracle claim is true is extraordinarily low, because we have an enormous background knowledge of the frequency of such claims being false.”

— Proving History (2012), p. 231

He concludes:

“When all relevant background knowledge and evidence are taken into account, I find it about one in three that Jesus existed as a historical person.”

— On the Historicity of Jesus (2014), p. 600

and openly admits, “These estimates depend on my priors.” (p. 601 n. 23)

Carrier’s near-zero starting point guarantees his result.

The mathematics merely reflects the assumption that divine action never happens.

9. How the Starting Assumption Changes the Outcome

| Approach | Starting Assumption (Prior for a Miracle) | Effect on Final Probability of Resurrection | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard Carrier (strict naturalism) | 0.01 % — miracles virtually impossible | < 1 % | Evidence cannot move a closed universe; resurrection remains “impossible.” |

| Moderate Prior (1 %) — Mackie / Draper style | 1 % — miracles rare but possible | ≈ 50 % | Balanced starting point lets credible testimony make belief reasonable. |

| Open Prior (10 %) | 10 % — God may act in history | ≈ 90 % | Same data now makes the resurrection the most probable explanation. |

The math is neutral; the priors are not.

Carrier begins so close to zero that no evidence could ever change the result.

Starting even modestly higher—1 % or 10 %—lets the evidence from Paul and the early witnesses actually speak.

10. Paul, the Gospels, and the Earliest Evidence

Even the most skeptical scholars—atheist or agnostic—agree on one remarkable fact: Paul of Tarsus is a genuine historical witness whose letters are the earliest Christian writings we possess.

Ehrman himself calls Paul’s testimony “the only firsthand account from someone who claimed to have seen Jesus alive after his death.” (How Jesus Became God, p. 183.)

That admission alone is striking: a first-century Pharisee, hostile to the movement, became convinced he had seen the risen Jesus and changed history.

Skeptical scholars often contrast Paul’s authentic letters with other New Testament writings such as 1 & 2 Peter, Jude, and James, which they consider forgeries.

Their primary reason is the highly polished Greek of these letters—language and rhetoric they believe unlikely for Galilean fishermen or village Jews who spoke Aramaic as a first language.

Other arguments are secondary: the letters’ developed theology, later church structures, and literary dependence on earlier texts.

Yet the use of amanuenses—professional secretaries or scribes—offers a historically plausible explanation.

The New Testament itself names Tertius as the scribe for Paul’s Letter to the Romans (Rom. 16:22) and mentions Silvanus as the intermediary or co-writer in 1 Peter 5:12.

Luke’s own prologue likewise reflects the work of a trained writer composing on behalf of others.

Such evidence makes it entirely credible that leaders like Peter, Jude, or James could have dictated or supervised letters written in sophisticated Greek by trusted collaborators—consistent with first-century literary practice rather than contrary to it.

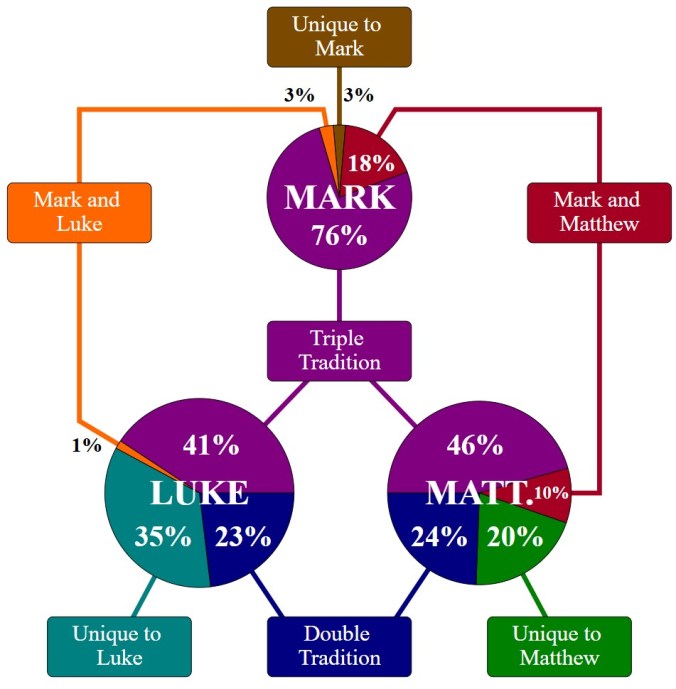

But Paul was not the first source of the resurrection claim.

In fact, Paul appears to quote or paraphrase written Gospel narratives at least three times in 1 Corinthians: Jesus’ teaching on divorce (1 Cor 7:10–11), His instruction that “those who proclaim the gospel should live by the gospel” (1 Cor 9:14), and the words spoken at the Last Supper (1 Cor 11:23–25).

These references correspond closely to passages preserved in the Synoptic Gospels—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—though Paul wrote around AD 54, well before critics think those Gospels were formally composed.

Whether he is paraphrasing from memory or citing a written source known to the churches, his allusions confirm that written accounts of Jesus’ teachings and final meal were already circulating within twenty years of the crucifixion.

This strongly supports Luke’s statement that “many have undertaken to compile a narrative” and pushes the origin of the Synoptic tradition—or versions of it—earlier than the mid-first century.

The Gospels as Multiple Independent Sources

The four Gospels preserve at least five independent streams of early information:

- Mark, our earliest narrative.

- Matthew’s unique material (M).

- Luke’s unique material (L).

- The sayings source (Q) shared by Matthew and Luke.

- The independent Johannine tradition more than 90% different than the synoptics.

Luke himself opens his Gospel acknowledging many earlier accounts and explaining his historical method in detail:

Luke 1:1–4 (ESV)

“Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us,

just as those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word have delivered them to us,

it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past,

to write an orderly account for you, most excellent Theophilus,

that you may have certainty concerning the things you have been taught.”

Luke’s Introduction: What It Implies

- “Many have undertaken …” – Luke’s Gospel is part of an already-active literary effort.

- Several written accounts existed before his, showing that Jesus’ life was being recorded early and from multiple angles.

- “Eyewitnesses and ministers …” – Luke affirms that his material derives from people present “from the beginning.”

- He places himself in the second generation: a historian gathering and arranging what eyewitnesses had handed down.

- “It seemed good to me also … to write an orderly account …” – Luke’s Greek indicates education and deliberate composition.

- Such writing often employed an amanuensis—a professional scribe—just as other New Testament authors mention Tertius (Rom 16:22) and Silvanus (1 Pet 5:12).

- Early Christians and their patrons worked together to preserve testimony in polished literary form.

- “For you, most excellent Theophilus …” – The dedication implies sponsorship by a wealthy or influential Roman believer.

- This hints at a pattern likely both before and after Luke: educated Christians with means supported the research, writing, and copying of the Gospel story.

- Such partnerships between patrons and writers help explain how high-level Greek compositions could emerge from a movement that began among Galilean laborers.

- “That you may have certainty …” – Luke writes to confirm, not invent, the message his audience already knows.

- Christianity spread through confidence that its message rested on verifiable history, not legend.

- From Aramaic fishermen to Greek historians.

- This collaboration between eyewitnesses, patrons, and literate scribes shows how the message of Jesus moved from illiterate Aramaic-speaking Jews in Judea to high-level Greek writings circulating across the Roman world within one generation.

- The very existence of Luke’s prologue demonstrates the extraordinary effort the earliest believers made to preserve what they had seen and heard.

The Two Early Creeds and the Christ Hymn

Within Paul’s letters we find ancient formulas he inherited, not invented—texts that even atheist historians date to within a few years of the crucifixion.

- The Resurrection Creed (1 Cor 15:3-5):

“For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that He was buried, that He was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that He appeared to Cephas, then to the Twelve, and to all the apostles.”

Every major critical scholar—Ehrman, Lüdemann, Dunn—dates this to A.D. 30–35, perhaps within months of the crucifixion.

- The Gospel Summary (Rom 1:3-4):

“Concerning His Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh and was declared to be the Son of God in power by His resurrection from the dead — Jesus Christ our Lord.”

- The Christ Hymn (Phil 2:6-11):

“Who, though He was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped … Therefore God has highly exalted Him …”

All three focus on Jesus’ death, resurrection, and exaltation.

Because Paul received them, their origin lies earlier than Paul—in the faith and worship of those who knew Jesus personally.

Paul’s Contact with the Earliest Witnesses

Three years after his conversion Paul went to Jerusalem “to visit Cephas and stay with him fifteen days; I saw none of the other apostles except James the Lord’s brother” (Gal 1:18-19).

Later he names James, Cephas, and John as pillars of the Jerusalem church (Gal 2:9).

Within a few years of the crucifixion, Paul had direct access to those who claimed to have seen Jesus alive.

Even if one accepts Ehrman’s skepticism about the Gospels, belief in the resurrection did not originate with Paul; he inherited it from a living network of witnesses already proclaiming it as the core of their faith.

11. Earliest Witnesses to the Resurrection

The Christian proclamation is rooted in testimony—people who said they personally saw Jesus alive after His death.

Those witnesses come from at least six independent sources—

Paul’s letters, Mark, Matthew’s material (M), Luke’s gospel material (L) along with Acts, the sayings source shared by Matthew and Luke (Q), and the independent Johannine tradition—

and, as Luke himself says, “many have undertaken to compile a narrative” (Luke 1:1).

That means still more written or oral accounts were circulating even before our four canonical Gospels.

| Witness / Group | Source(s) | Setting or Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mary Magdalene | Mark 16 : 1-8 (abr.), Matt 28 : 1-10, Luke 24 : 1-11, John 20 : 1-18 | Arrives first at the tomb; sees the stone removed; in John, meets the risen Jesus and hears her name. |

| Mary the mother of James, Salome, Joanna, and “other women” | Mark 16 : 1-8; Luke 24 : 10; Matt 28 : 1 | Accompany Mary Magdalene; encounter angels announcing the resurrection. |

| Peter (Cephas) | 1 Cor 15 : 5; Luke 24 : 34 | Private appearance soon after the tomb discovery. |

| The Eleven (“the Twelve”) | 1 Cor 15 : 5; Luke 24 : 36-49; John 20 : 19-23; Matt 28 : 16-20 | Group appearance in Jerusalem; Jesus shows wounds, eats with them, and commissions them. |

| Cleopas and his companion (on the road to Emmaus) | Luke 24 : 13-35 | Two disciples recognize Jesus in the breaking of bread. |

| Thomas (with the others a week later) | John 20 : 24-29 | Invited to touch Jesus’ wounds; confesses, “My Lord and my God.” |

| Seven disciples at the Sea of Galilee (Peter, Thomas, Nathaniel, James, John, and two others) | John 21 : 1-14 | Breakfast by the sea; Jesus restores Peter. |

| “More than five hundred brothers and sisters at once” | 1 Cor 15 : 6 | Collective appearance—unique in ancient literature; Paul notes that most were still alive. |

| James (the Lord’s brother) | 1 Cor 15 : 7; Gal 1 : 19 | Once skeptical (John 7 : 5); later leader of the Jerusalem church. |

| “All the apostles” (broader missionary circle) | 1 Cor 15 : 7 | Broader group beyond the Twelve. |

| Paul of Tarsus | 1 Cor 15 : 8; Acts 9 : 1-19 | Later appearance—“last of all… as to one untimely born.” |

Key Observations

- The witnesses span both genders, multiple social levels, and private and group experiences.

- The tradition lists named people, many of whom were still alive when the letters circulated—an open invitation to verify.

- The creeds and hymn Paul “received” are dated by even skeptical scholars (Ehrman, Lüdemann, Dunn) to within five years of the crucifixion.

- No other ancient religion begins with such a network of living witnesses claiming to have seen the same person alive again.

12. The Pagan Parallel: Apollonius of Tyana

Some critics have suggested that stories of Jesus’ miracles and resurrection merely echo pagan legends such as Apollonius of Tyana—a first-century philosopher and wonder-worker who lived around AD 15 to 100.

At first glance the comparison sounds plausible: both figures are described as miracle workers.

But when we examine the sources historically, the parallels collapse.

The differences in number of witnesses, consistency of narrative, time gap between event and record, and the moral and social impact of the movements are enormous.

| Category | Jesus of Nazareth (d. AD 30) | Apollonius of Tyana (c. AD 15–100) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Sources | Four Gospels (Mark, Matthew, Luke, John) + Acts + independent early material (M, L, Q) + Paul’s letters (esp. 1 Cor 15) | Life of Apollonius by Philostratus, written c. AD 220–230 — about 120 years after Apollonius’ death |

| Time Between Events and Accounts | Within one generation (20–40 yrs); Paul’s creeds within ≈ 5 yrs of the crucifixion | Roughly 120 yrs after events; no contemporary documentation |

| Number of Named Witnesses | Dozens of named individuals (Mary Magdalene, Peter, James, John, Thomas, etc.) plus groups up to ≈ 500 people (1 Cor 15) | None contemporary; Philostratus claims to use a lost memoir by “Damis,” a follower never verified |

| Consistency of Death / Resurrection Stories | Unified pattern: crucifixion under Pilate → burial → empty tomb → multiple appearances proving resurrection | Philostratus admits “many stories” about Apollonius’ death and disappearance (8.30–31); no single version agreed upon |

| Nature of “Resurrection” or Departure | Bodily resurrection attested by multiple witnesses who claimed physical contact and verbal interaction | A single-person vision not verified even by those with the person; one death story has him vanishing in a temple but no witnesses. |

| Community and Continuity | Immediate movement spreading through eyewitness preaching about his resurrection and willingness to die for it. Key enemies of the faith converted due to resurrection encounters (Paul and James, Jesus’ brother) | No lasting cult or ethical movement; admiration remained literary and elite |

| Writers’ Admission of Sources | Luke explicitly cites “many accounts” based on eyewitnesses and ministers of the word (Luke 1:1–4) | Philostratus offers hearsay and conflicting legends, openly admitting uncertainty with one unverified source |

| Overall Character | Early, multi-sourced, historically anchored, morally transformative | Late, single-sourced, contradictory, purely literary |

Conflicting Endings in the Life of Apollonius

“…as for the manner of his death—if he really died—there are many stories, though Damis repeats none of them…

Some say he died in Ephesus, cared for by two maidservants…

Others say he died in Lindus, where he entered the temple of Athena and disappeared. Others again claim that he died on Crete in a far more remarkable way. One night he went to the temple of Dictynna. The fierce watchdogs guarding it fawned on him instead of barking. The guards, thinking him a sorcerer, bound him. About midnight he freed himself, called his captors to watch, ran to the temple doors, which opened by themselves; he entered, the doors shut, and from within came a chorus of maidens singing, ‘Hasten from earth, hasten to heaven, hasten…’

Later, in Tyana, a young skeptic denied the immortality of the soul, saying, ‘I have prayed to Apollonius for nine months to show me the truth, but he is so utterly dead that he will not appear.’ Five days later, while discussing the same topic, the youth leapt up, drenched in sweat, crying, ‘I believe you, Apollonius!’ He said that Apollonius was present, unseen to others, reciting verses about the soul:

‘The soul is immortal; it is not yours but Providence’s.

When the body wastes away, it leaps forward like a freed horse,

Mingling with the light air and escaping the painful slavery it endured.

But for you—why worry? When you are gone, you will know.’Here we find a clear statement from Apollonius, standing firm like a prophetic guide, meant to help us understand the mysteries of the soul—so that, with confidence and a true awareness of who we are, we can move forward toward the destiny set for us. I have travelled the whole earth, and I know of no tomb of him anywhere, though his shrine at Tyana is honored with imperial guardianship.”

— Philostratus, Life of Apollonius of Tyana 8.30–33 (Loeb Classical Library II, pp. 399–407)

What These Passages Show

- Multiple death stories: at least three contradictory versions—Ephesus, Lindus, and Crete—with Philostratus openly acknowledging “many stories.”

- No eyewitness testimony: his supposed companion Damis “repeats none.” All are anonymous hearsay recorded more than a century later.

- A single private vision: one young man alone claims to see Apollonius reciting verses; no one else perceives anything.

- Unremarkable teaching: the message is a generic claim that the soul is immortal and a dismissal of inquiry—“you’ll find out when you die.”

- No enduring movement: the story ends with a civic shrine, not a community transformed by moral conviction.

In summary:

Apollonius’ ending is late, contradictory, and philosophically shallow—a literary imitation of divine ascent rather than a historical claim verified by witnesses.

The resurrection of Jesus, by contrast, was proclaimed within years by many named witnesses and launched a movement that reshaped the moral and spiritual history of the world.

13. Visions and New Religious Movements Across History

The resurrection of Jesus stands within a broader human pattern of visions and revelations that have launched new faiths or sects.

But in every other case the experiences are isolated, private, and far removed from public verification.

Christianity began with numerous named witnesses claiming to have seen the same person alive again—an unparalleled claim in religious history.

| Figure / Movement (approx. date of founding vision) | Core Vision Claim (Who / When) | How Many Claimed to See? | Net-New Movement or Sect Formed? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jesus of Nazareth (c. AD 30) | Resurrection appearances – Cephas, the Twelve, ≈ 500 at once, James, all apostles, Paul (1 Cor 15); plus women (Mary Magdalene, Mary mother of James, Salome, Joanna etc.), Cleopas and companion (Emmaus), the Eleven (Jerusalem), and seven disciples (Galilee). | Many – groups and crowds | Yes → Christianity |

| Romulus (8th cent. BCE) | Post-mortem appearance to Proculus Julius after disappearance. | 1 | No (state cult only) |

| Zoroaster (c. 1200–600 BCE) | Foundational vision of Ahura Mazda via Vohu Manah. | 1 | Yes → Zoroastrianism |

| Asclepius cult (5th–4th cent. BCE) | Healing dream-visions in temples (Epidaurus etc.). | Many (private) | Expansion of existing cult |

| Apollonius of Tyana (c. AD 15–100) | Contradictory death accounts; later one young man claims vision of him reciting verses about the soul. | 1 | No (enduring cult absent)** |

| Simon Magus (mid-1st cent. AD) | Magical signs and visions recorded by followers. | 1 (+ followers) | Yes → early sect |

| Mani (AD 228 & 240) | Revelatory visions; claims prophetic commission. | 1 | Yes → Manichaeism |

| Muhammad (AD 610) | Revelation through Gabriel beginning at Ḥirāʾ. | 1 | Yes → Islam |

| Montanus with Priscilla & Maximilla (c. AD 156–172) | Trance-prophecies and visions of Spirit’s coming (New Prophecy). | 3 | Sect within Christianity |

| Guru Nanak (c. 1500) | Vision after three-day disappearance in River Bein. | 1 | Yes → Sikhism |

| Sabbatai Zevi (AD 1648–1666) | Ecstatic visions; declares himself Messiah; later apostasy. | 1 (+ followers) | Yes → Sabbatean sects |

| Israel ben Eliezer, “Baal Shem Tov” (c. 1700–1760) | Jewish mystic whose visions and ecstatic prayer experiences inspired the rise of Hasidic Judaism. Claimed encounters with angels and a vision of the Messiah saying redemption would come when his teachings spread. | 1 (primary seer) | Yes → Hasidic movement within Judaism |

| Emanuel Swedenborg (AD 1744–1745) | Visions of heaven and hell. | 1 | Yes → Church of the New Jerusalem |

| Ann Lee (c. AD 1770) | Visions of Christ’s “second appearing.” | 1 | Yes → Shaker movement |

| Handsome Lake (1799) | Series of visions inspiring Iroquoian reform. | 1 | Yes → Longhouse Code |

| Native American Vision Ceremonies (ancient → present) | Vision-seeking through fasting, isolation, or sacramental plants (e.g., Plains vision quest, peyote rites of the Native American Church). Experiences interpreted as encounters with spirit beings or the Great Spirit. | Individuals or small groups in ritual context | No – practice within Indigenous traditions (Native American Church formalized 19th–20th cent.) |

| Joseph Smith (1820–1829) | “First Vision” (1820: God the Father & Jesus Christ); angel Moroni visitations (1823–29); later Three Witnesses & Eight Witnesses see gold plates but no divine figures. | 1 (primary seer) + 11 plate witnesses | Yes → Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints |

| Ellen G. White (1844 – 1915) | Extensive visions and dreams guiding doctrine and practice throughout her ministry. | 1 | Yes → Seventh-day Adventist Church |

| The Báb (AD 1844) | Night-long revelation and public declaration. | 1 | Yes → Bábism |

| Bahá’u’lláh (AD 1852–1863) | Prison theophany and Ridván declaration. | 1 | Yes → Bahá’í Faith |

| Black Elk (1872) | “Great Vision” at age 9. | 1 | Cultural renewal movement |

| Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1882–1889) | Divine revelations and visions. | 1 | Yes → Ahmadiyya Islam |

| Deguchi Nao (1892) | Possession / revelations of “Ushitora no Konjin.” | 1 | Yes → Ōmoto |

| Hong Xiuquan (1837–1843) | Visions claiming to be Jesus’ younger brother. | 1 | Yes → Taiping movement |

| Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson (1902–1994) | Revered leader of the Chabad-Lubavitch movement; after his death, a minority of followers within this already small Hasidic branch claimed to see him in visions and expected his messianic return. He remains buried in a verifiable tomb (the Ohel, Queens, New York). | Small number of individual claimants | No – renewal and expectation within Judaism (not a new religion) |

| Sun Myung Moon (1936) | Vision of Jesus at age 16; church founded 1954. | 1 | Yes → Unification Church |

| Catholic Marian Apparitions (1531 → present) | Reported appearances of Mary (e.g., Guadalupe 1531; Lourdes 1858; Fátima 1917; Zeitoun 1968–71). The Church has officially recognized ≈ 16 of more than 1,500 reported apparitions worldwide after rigorous investigation. Most involve one or a few seers, occasionally crowds of tens of thousands. | Variable – usually 1 to few; occasionally crowds | No – devotional renewal within Catholic faith |

Ancient accounts of the Asclepius healing temples—especially at Epidaurus, Pergamum, and Kos—show that visions and even miraculous healings were part of Greco-Roman religious life.

The process was deliberate and carefully prepared:

- Purification and preparation: visitors bathed in sacred springs, fasted, and wore clean garments before entering the abaton, the inner sanctuary where they would sleep.

- Offerings and prayer: worshippers made small sacrifices and prayed for a dream or appearance of Asclepius to reveal the cure.

- Incubation: during the night they expected the god—often depicted as a physician or serpent—to appear and prescribe or perform healing.

- Interpretation and testimony: priests interpreted the dreams the next morning, and those who claimed to be healed offered public inscriptions describing what had happened.

Sources such as Pausanias, Aelius Aristides, and the Epidaurian inscriptions record numerous cases of healing and divine encounters.

There is no reason to doubt that people in these temples had powerful visionary or even miraculous experiences.

But these accounts are not comparable to the resurrection appearances of Jesus.

Every Asclepian vision was sought through ritual expectation—participants came prepared, purified, and hoping to see the god.

The resurrection appearances, by contrast, occurred among people who were not expecting anything: they were frightened, defeated, and convinced that Jesus was dead.

Whatever one concludes about either set of experiences, the context and character of the events are entirely different—ritual healing visions in a temple versus unexpected encounters with a crucified man alive again.

Key Contrasts

- Apart from Jesus’ resurrection, every founding vision in history begins with one person or a very small circle claiming a private experience.

- None involve hundreds of simultaneous eyewitnesses or early written creeds within years of the claimed event.

- Most other revelations appear centuries after the traditions they reference, whereas the resurrection was proclaimed immediately within its own culture.

- Devotional phenomena such as Marian apparitions, Native American vision ceremonies, and post-Rebbe expectations renew existing faiths but do not create new religions.

14. Visions: Real, Mistaken, or Manufactured?

History has to allow three possibilities whenever someone claims a vision:

- They truly perceived something real (veridical).

- They misperceived—a dream, illusion, or grief-induced image (non-veridical).

- They fabricated the claim (deception).

The New Testament openly acknowledges this range and calls for discernment:

- “Test the spirits to see whether they are from God, for many false prophets have gone out into the world.” — 1 John 4:1–3

- “Even if we or an angel from heaven should preach a different gospel, let him be accursed.” — Galatians 1:8–9

- “Satan disguises himself as an angel of light.” — 2 Corinthians 11:14–15

- Jesus warned that false christs and false prophets would perform “great signs and wonders” to mislead, “even the elect if possible.” — Matthew 24:23–26

- The Colossian letter also acknowledges teachers who practiced the worship of angels and boasted about visions they had seen: “Do not let anyone who delights in false humility and the worship of angels disqualify you. Such a person goes into great detail about what they have seen; they are puffed up with idle notions by their unspiritual mind. They have lost connection with the Head, from whom the whole body grows.” — Colossians 2:18–19

The early apologist Origen made the same point when replying to pagan critics: some wonders are tricks or demonic imitations, but Jesus’ works differ in moral effect:

“We know of many who have deceived multitudes by magical illusions, but Jesus’ works were not such, for they reformed those who beheld them.” — Contra Celsum 2.48

Why the Earliest Christian Claims Stand Apart

- Breadth and convergence: not one seer but a network of named witnesses—women at the tomb, Peter, the Eleven, the Emmaus pair, the Galilee seven, about 500 at once, James, all the apostles, and finally Paul.

- Public, embodied encounters: appearances in groups, with touch, conversation, and shared meals—claims open to verification, not private impressions.

- Earliest focus on a single historical event: pre-Pauline creeds and hymn (1 Cor 15:3–5; Rom 1:3–4; Phil 2:6–11) already center on death → burial → resurrection → exaltation.

- Costly conviction: those witnesses proclaimed what they saw at great personal risk; they gained no wealth or power, only hardship and martyrdom.

Christianity therefore recognizes that visions can be true, mistaken, or manufactured, yet the resurrection testimony remains unique on every historical test—number, independence, embodiment, and enduring moral consequence.

15. The Greater Miracle

David Hume challenged the world to ask which is more probable:

that witnesses of a miracle are deceived, or that the miracle actually occurred.

Across history, countless founders and visionaries have claimed revelations—usually alone, often private, and rarely verifiable.

But the resurrection of Jesus stands apart:

- Multiple named witnesses—men and women, groups and crowds—claimed to see the same person alive again.

- Independent, early sources—Paul’s letters, the Gospels, and Acts—record the claim within a generation.

- A unified message—death, burial, resurrection, exaltation—runs across all streams of tradition.

- A moral and social transformation followed: those who once fled in fear became proclaimers willing to suffer and die.

If all this were false, we must believe that hundreds across diverse settings shared the same deception and that a movement built on that deception outlasted the empires that tried to crush it.

If it is true, then history has been opened to its Author.

So Hume’s question remains the right one:

Which is the greater miracle—

that so many credible witnesses were deceived,

or that the resurrection they proclaimed really happened?