40% Growth Then, 5% Growth Now — What We Must Learn Anew

When Nero died by suicide in AD 68, the Roman Empire plunged into chaos.

In a single year four emperors—Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and finally Vespasian—rose and fell.

While Rome fought for power, Judea was already on fire.

The revolt that began under Gessius Florus would end with Jerusalem leveled, the Temple burned, and a turning point for both Jews and Christians.

1. Florus and the Spark of Revolt (AD 66)

Florus, the Roman governor of Judea, stole seventeen talents of silver from the Temple treasury—about 1,200 pounds of consecrated silver, worth roughly ten million U.S. dollars today.

This was not ordinary corruption; it was sacrilege.

“When Florus took seventeen talents out of the sacred treasure, and the multitude ran together in the Temple crying out against him, some of the youths went about the city carrying baskets and asking alms for poor Florus.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 2.14.5 §306–308 (c. AD 75–79)

His answer was bloodshed.

“Florus sent soldiers into Jerusalem and ordered a massacre. They slew about three thousand six hundred persons, women and children as well as men; and among them were citizens of Roman knighthood. Some were scourged and then crucified.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 2.14.9 (c. AD 75–79)

The outrage united the city. Rebels stormed the Antonia Fortress, the great Roman garrison on the northwest corner of the Temple Mount. To capture it was to challenge Rome itself.

“They compelled the garrison to surrender and then slaughtered them. Thus war was now openly begun.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 2.17.9 (c. AD 75–79)

Rome’s patience ended. Nero sent Vespasian, the empire’s most seasoned general, and his son Titus to crush the rebellion.

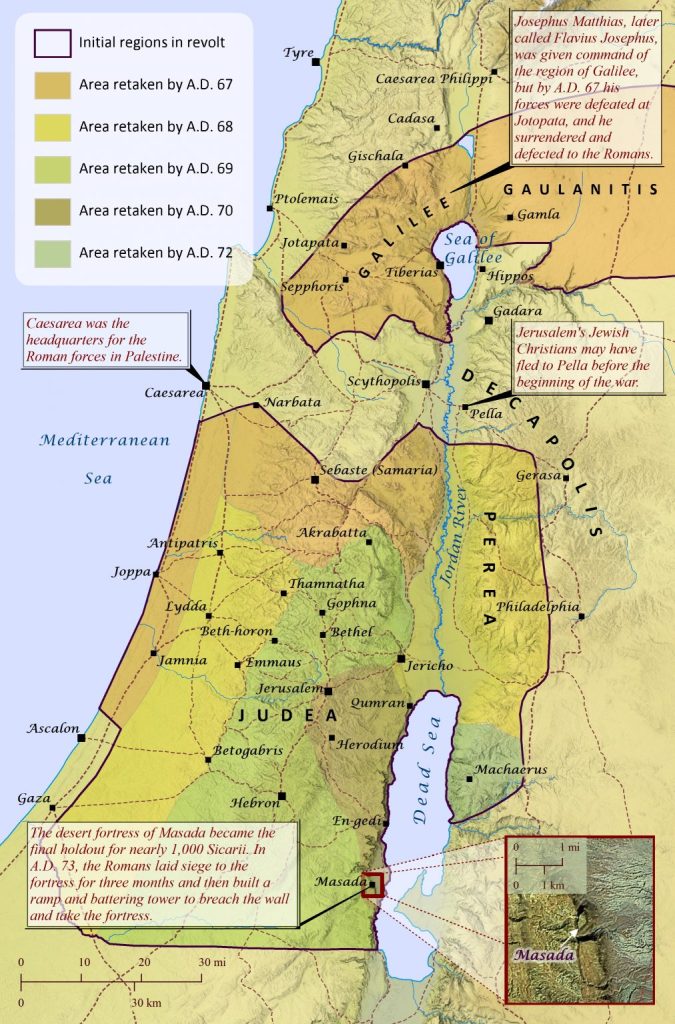

2. Vespasian in Galilee — Fire and Terror (AD 67)

Galilee became Rome’s first target. At Jotapata, a hill fortress commanded by Josephus himself, the walls fell after forty-seven days.

“Forty thousand were slain, and the city was utterly demolished; those who had hidden in caves were dragged out and slain.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 3.7.36 (c. AD 75–79)

Then came Gamla, a ridge-top city east of the Sea of Galilee. Its name means camel in Aramaic, and its fall was as steep as its slopes.

“Men and women alike threw themselves and their children down the precipices; and the whole city was covered with corpses.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 4.1.9 (c. AD 75–79)

Josephus summed it simply: “Galilee was filled with fire and blood.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 4.1.9 (c. AD 75–79)

The Roman campaign left the region in ruins, silencing nearly every center of resistance.

It was here that Josephus himself was captured. As commander of Jewish forces in Galilee, he had held out at Jotapata until the city fell. In his own account, he claims that while in captivity he prophesied that Vespasian would soon be emperor:

“You, O Vespasian, shall be Caesar and emperor, you and your son. Bind me now still closer, and keep me for yourself; for you, O Caesar, are lord, not only of me, but of the land and sea, and of all mankind.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 3.8.9 §401–403 (c. AD 75–79)

When that prophecy appeared to come true the following year, Vespasian spared his life, granted him Roman citizenship, and attached him to his household. From then on Josephus lived in Rome under imperial patronage, taking the family name Flavius from his patrons.

This is how Yosef ben Matityahu, a Jewish priest and rebel general, became Flavius Josephus, historian of the Jewish War. His writings—sometimes defensive, sometimes deferential toward Rome—remain the only detailed eyewitness record of Jerusalem’s destruction.

3. The Siege of Jerusalem (AD 70)

When Nero’s death recalled Vespasian to Rome, Titus took full command.

Inside Jerusalem, zealot factions fought one another while Roman legions built a five-mile siege wall to starve the city into surrender.

This wall—called a circumvallation—completely encircled Jerusalem. Built in only three days by tens of thousands of soldiers, it cut off every road and stopped all supplies. Famine would finish what the legions began.

“The famine grew severe and destroyed whole houses and families. The alleys were filled with dead bodies of the aged; children and youths swarmed about the market-places like shadows, and fell wherever famine overtook them. No one buried them; pity was strangers to men; for famine had confounded all natural feeling.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 5.12.3–4 (c. AD 75–79)

Then Josephus records one of antiquity’s darkest scenes:

“There was a certain woman named Mary, daughter of Eleazar, of the village Bathezor. Driven by famine and rage, she slew her infant son, roasted him, and ate one half, concealing the rest. When the soldiers smelled the roasted meat and rushed in, she said, ‘This is my own son; the deed is mine; eat, for I have eaten. Do not pretend to be more tender-hearted than a woman or more compassionate than a mother.’”

— Josephus, Jewish War 6.201–213 (c. AD 75–79)

Titus later claimed he had ordered the Temple spared:

“I myself called a council of war and urged that the Temple be saved; but the flame was beyond control, and the sanctuary was burned against my will.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 6.4.7 §254 (c. AD 75–79)

Josephus blames undisciplined troops; Tacitus sees deliberate policy:

“It was resolved to destroy the Temple that the religion of the Jews might be more completely abolished.”

— Tacitus, Histories 5.12 (c. AD 100–110)

Different motives, same outcome: the Temple fell.

For Christians, it confirmed the prophecy of Christ: “Not one stone shall be left upon another.” (Mark 13:2)

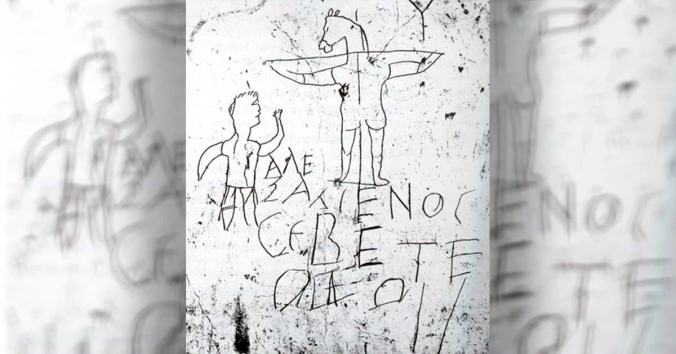

4. Crosses Without Number

“As for those who had fled from the city and were caught, they were first scourged and then tortured and finally crucified before the walls. In their fury and hatred the soldiers nailed up the prisoners in different postures, by way of jest, and the multitude was so great that room was wanting for the crosses, and crosses for the bodies.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 5.11.1 (c. AD 75–79)

Josephus later expands this account:

“Those who were taken outside the city he first scourged, and then tormented with all manner of tortures before crucifying them opposite the wall. Titus indeed felt pity for them, but their number was so great that there was no room for the crosses nor crosses for the bodies. About five hundred were crucified each day, and the soldiers, in their rage and hatred, amused themselves by crucifying some one way and some another, until, owing to the multitude, there was no space left for the crosses nor crosses for the bodies.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 6.1.1 (c. AD 75–79)

The same empire that boasted of order and civilization turned execution into entertainment.

The hills around Jerusalem stood thick with crosses—not yet symbols of redemption, but monuments of Rome’s rule through fear.

5. Aftermath — Slavery, Spectacle, and Tax

Through Rome’s streets the captives marched, carrying the Menorah and sacred vessels. Coins were struck proclaiming IUDAEA CAPTA—“Judea Captured.” Various versions of these coins were struck and used for 25 years under Vespasian and his two sons Titus and Domitian.

“He decreed that all Jews throughout the world should pay each year two drachmas to the Capitol in Rome, as they had previously paid to the Temple in Jerusalem.”

— Dio Cassius, Roman History 66.7 (c. AD 200–220)

The fiscus Judaicus turned a holy offering into tribute for pagan gods.

Jewish Christians, still classed as Jews, were forced to pay the same tax of defeat.

Meanwhile, many early believers saw a deeper reason for Jerusalem’s ruin: the death of James the Just, the brother of Jesus and leader of the church in Jerusalem.

“Festus was now dead, and Albinus was but upon the road; so Ananus, who had become high priest, assembled the Sanhedrin of judges, and brought before them the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James, and some others; and when he had formed an accusation against them as breakers of the law, he delivered them to be stoned.”

— Josephus, Antiquities 20.9.1 §200–203 (c. AD 93)

Hegesippus, a second-century Jewish Christian, adds detail:

“They placed James on the pinnacle of the Temple and cried, ‘Tell us, O righteous one, what is the door of Jesus?’ And he answered with a loud voice, ‘Why do you ask me concerning the Son of Man? He sitteth at the right hand of the Great Power, and shall come on the clouds of heaven.’ Then they began to stone him, and a fuller took the club with which he beat clothes and struck the righteous one on the head, and so he suffered martyrdom.”

— Hegesippus in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.23.10–12 (c. AD 170, quoted c. AD 310–325)

Hegesippus concludes that the siege of Jerusalem followed soon after James’s death, calling it divine judgment:

“Immediately after this Vespasian began to besiege them; and they remembered the saying of Isaiah the prophet, ‘Let us take away the righteous man, because he is troublesome to us; therefore they shall eat the fruit of their doings.’ Such was their lot, and they suffered these things for the sake of James the Just.”

— Hegesippus in Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.23.18 (c. AD 170, quoted c. AD 310–325)

Eusebius agrees, closing his account:

“These things happened to the Jews to avenge James the Just, who was the brother of Jesus that is called Christ. For, as Josephus says, these things befell them in accordance with God’s vengeance for the death of James the Just, which they had committed, although he was a most righteous man.”

— Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 2.23.19–20 (c. AD 310–325)

From this moment on, many Christians saw the destruction of Jerusalem not only as Rome’s triumph, but as God’s judgment for rejecting Christ and murdering His righteous servant.

6. The Arch of Titus — The Empire’s Theology in Stone (AD 81)

When Titus died, the Senate declared him divine. The arch still standing on the Via Sacra reads:

“The Senate and People of Rome [dedicated this] to the deified Titus Vespasian Augustus, son of the deified Vespasian.”

Inside its vault, carvings show Roman soldiers bearing the Temple treasures.

“They brought the Menorah and the table of the bread of the Presence, and the last of the spoils was the Law of the Jews; after these, a great number of captives followed.”

— Josephus, Jewish War 7.5.5 (c. AD 75–79)

For Rome, the arch proclaimed the victory of its gods.

For Christians, it stood as a silent confirmation of prophecy: the Temple of stone was gone, but the Temple of Christ remained.

7. The Flight to Pella — Revelation and Refuge

Amid the ruins of Jerusalem’s revolt, one community escaped—the believers who remembered Christ’s warning to flee.

“The people of the church in Jerusalem had been commanded by a revelation, vouchsafed to approved men there before the war, to leave the city and to dwell in a certain town of Perea called Pella. And when those who believed in Christ had come thither from Jerusalem, then, as if the holy men had altogether deserted the royal city of the Jews and the whole land of Judea, the judgment of God at last overtook them for their abominations.”

— Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History 3.5.3 (c. AD 310–325)

Eusebius attributes their escape to a divine revelation, while Epiphanius explains it as obedience to Christ’s prophecy:

“When all the disciples were settled in Pella because of Christ’s prophecy about the siege, they remained there until the destruction of Jerusalem.”

— Epiphanius, Panarion 29.7.7–8 (c. AD 375)

Different explanations—same event. The believers crossed the Jordan to Pella, a Decapolis city about sixty miles northeast of Jerusalem, where they waited out the war.

Their flight fulfilled Jesus’ own words (Luke 21:20–21).

What looked like retreat was obedience.

8. The Nazarenes — Law-Observant, Christ-Confessing

The first branch to emerge from that exile was the Nazarenes—Jewish believers who kept the Mosaic Law yet confessed Jesus as the divine Son of God.

They were the losing party in the Council of Jerusalem (Acts 15).

At that council, certain men from Judea began teaching that Gentile converts must keep the Law of Moses to be saved:

“Some men came down from Judea and were teaching the brothers, ‘Unless you are circumcised according to the custom of Moses, you cannot be saved.’”

— Acts 15:1

Later Luke identifies who pressed the issue:

“But some of the sect of the Pharisees who believed rose up, saying, ‘It is necessary to circumcise them and to command them to keep the law of Moses.’”

— Acts 15:5

Peter and James ruled that Gentiles need not bear that yoke:

“We should not trouble those of the Gentiles who turn to God, but should write to them to abstain from things polluted by idols, from sexual immorality, from what has been strangled, and from blood.”

— Acts 15:19–20

Those Jewish believers who could not release Torah observance continued as a community of Torah-keeping Christians—the Nazarenes.

Two decades later they were still strong. When Paul returned to Jerusalem near the end of his ministry, James the Just, the same leader later martyred near the Temple, recognized their influence:

“You see, brother, how many myriads of Jews there are who have believed, and they are all zealous for the Law… Therefore do what we tell you: we have four men who have taken a vow; take them and purify yourself along with them, and pay their expenses, so that all may know that there is nothing in what they have been told about you, but that you yourself also live in observance of the Law.”

— Acts 21:20, 23–24

James’s advice shows that the Nazarenes were not fringe but central within the Jerusalem church.

Centuries later, Jerome described them:

“The adherents to this sect are known commonly as Nazarenes; they believe in Christ the Son of God, born of the Virgin Mary; and they say that He who suffered under Pontius Pilate and rose again is the same as the one in whom we believe.”

— Jerome, Letter 75 to Augustine (AD 398–403)

“The Nazarenes accept Messiah in such a way that they do not cease to observe the old Law.”

— Jerome, Commentary on Isaiah 8:14 (AD 398–403)

Even Epiphanius, who condemned most sects, writes:

The Nazarenes are Jews who keep the customs of the Law but also believe in Christ. They say that Jesus was born of the Virgin Mary by the Holy Spirit. They believe that God created all things, that Jesus is His Son, and that the resurrection of the dead has already begun in Him… As for their understanding of Christ, I am not certain—whether they have been misled by false teachers who call Him merely human, or whether, as I think, they confess that He was born of Mary by the Holy Spirit.

— Epiphanius, Panarion 29.7.5–6 (c. AD 375)

Epiphanius lists their beliefs as orthodox and then admits, “I cannot say whether they have been deceived or whether they confess the truth.”

Had they denied Christ’s divinity, he would have said so.

His hesitation confirms that the Nazarenes were orthodox in belief, Jewish in culture—the first generation of Messianic Jews bridging synagogue and church.

9. The Ebionites — The First Denial of Christ’s Divinity

A second group took a different path. Epiphanius places their origin after the flight to Pella:

“The Ebionites are later than the Nazoraeans… their sect began after the flight from Jerusalem.”

— Epiphanius, Panarion 29.7.7–8 (c. AD 375)

They taught that Jesus was a mere man chosen by God, denied the virgin birth, and altered Scripture to fit their beliefs.

“Those who are called Ebionites use the Gospel according to Matthew only, and repudiate the Apostle Paul, maintaining that he was an apostate from the Law.”

— Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.26.2 (c. AD 180)

“The Ebionites believe that He was a mere man, born of Joseph and Mary according to the common course of nature, and that He became righteous through the progress of His moral character.”

— Origen, Commentary on Matthew 16.12 (c. AD 248)

“They falsify the genealogical tables in Matthew’s Gospel, saying that He was begotten of a man and a woman, because they maintain that Jesus is really a man and was justified by His progress in virtue, and that He was called Christ because the Spirit of God descended upon Him at His baptism. They say that this same Spirit, which had come upon Him, was taken away and left Him before the Passion and went back to God; and that then, after His death and resurrection, this same Spirit returned to Him again. Thus they deny that He is God, though they do not deny that He was a man.”

— Epiphanius, Panarion 30.14.3–5 (c. AD 375)

They also spread a slander about Paul:

“They say that Paul was a Greek who came to Jerusalem and lived there for a time. He desired to marry a daughter of the priests but was refused. Out of anger and disappointment he turned against circumcision, the Sabbath, and the Law. Because of this, they claim, he wrote against these things and founded a new heresy.”

— Epiphanius, Panarion 30.16.6–9 (c. AD 375)

For the Ebionites, Jerusalem’s destruction was not punishment for rejecting Christ but for accepting the apostolic Gospel.

They blamed Paul and the church that followed him for turning Israel away from the Law.

Thus they reversed the very lesson of history that Josephus, Hegesippus, and Eusebius had drawn from the death of James the Just.

Where the Nazarenes preserved unity in diversity, the Ebionites cut themselves off from the apostolic faith.

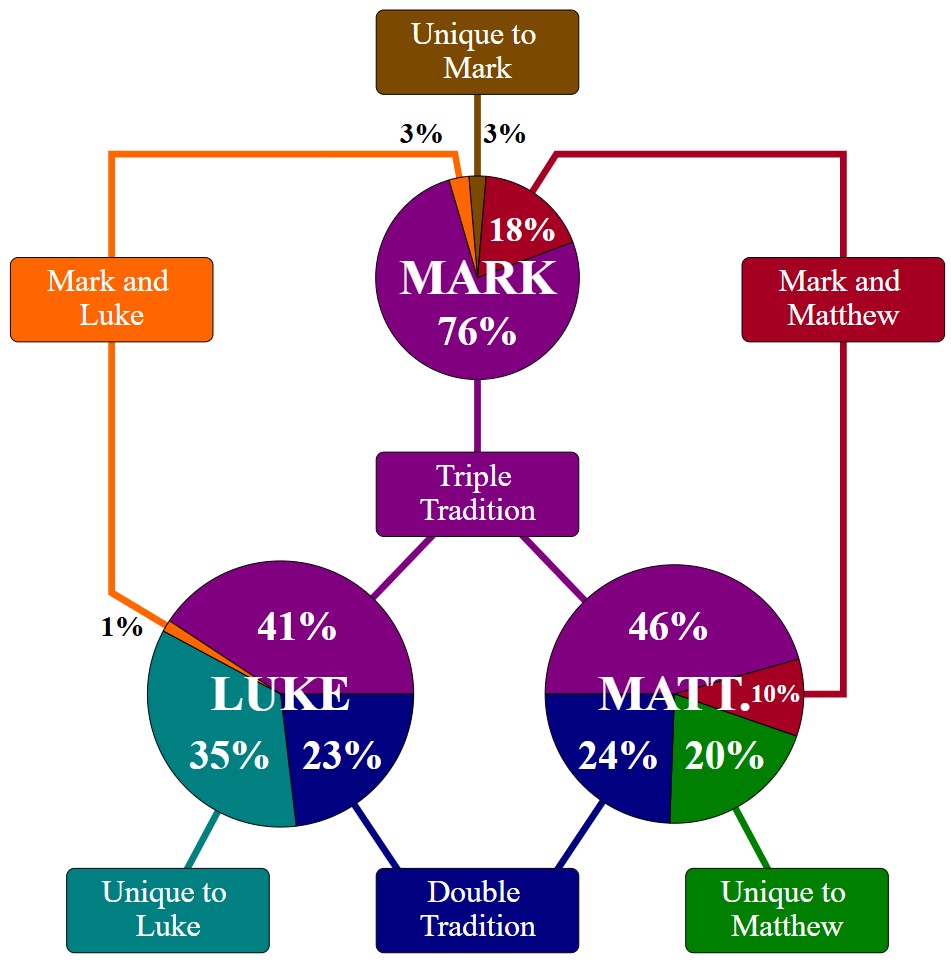

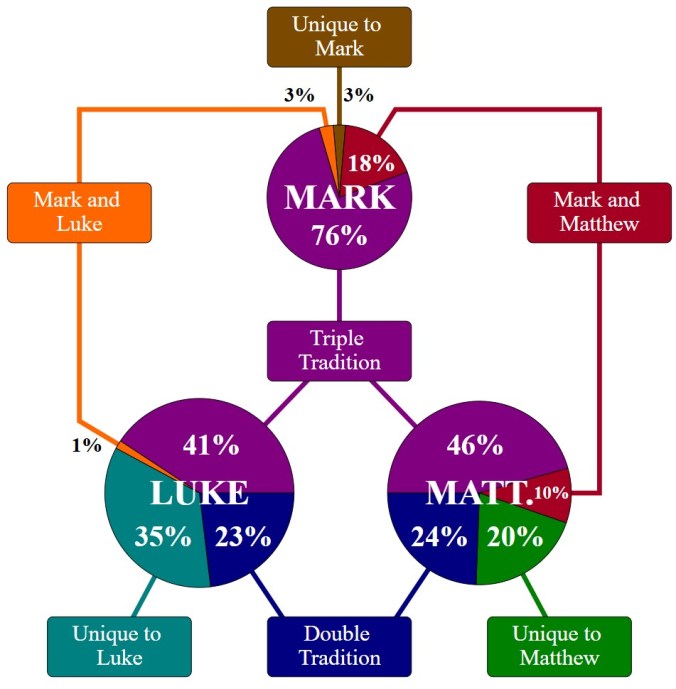

10. Three Waves of Testimony and the Apostolic Standard

When we date the earliest Christian writings, we find three waves of testimony—sources acknowledged even by skeptical historians as genuine first-century evidence.

They give us the historical core around which all later writings revolve.

Three Waves of Early Christian Testimony

| Wave of Witness | Approximate Date | Content & Description | Authority and Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Creeds | AD 30s | 1 Corinthians 15:3–5 — “Christ died, was buried, and rose again according to the Scriptures.” Philippians 2:6–11 — The Christ-hymn proclaiming His pre-existence, incarnation, humility, and exaltation. | The earliest confessions of faith; already proclaim Jesus as divine and demand worship. |

| Paul’s Epistles | AD 48–61 | The seven undisputed letters of Paul — Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon. | The interpretation of Christ’s work by Paul himself, written within the lifetime of the apostles; Paul quotes and affirms the early creeds as authoritative revelation. |

| Synoptic Gospels | AD 50s–60s | Matthew, Mark, and Luke — written within the first generation after Jesus, preserving eyewitness memory of His life, teaching, death, and resurrection. | The formal written record of what the earliest witnesses proclaimed; confirms and expands the message already present in the creeds and letters. |

This Philippians hymn is not later theology; it is the earliest Christian confession we possess.

It begins with divinity, not humanity.

It declares that the one “existing in the form of God” became man, died on a cross, and was exalted so that every knee should bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord.

It is a proclamation of His divinity and a demand for worship from the very start of the Christian movement.

Modern critics such as Bart Ehrman claim that belief in Jesus’ divinity was a late development, yet their own dating of the evidence proves the opposite.

The earliest sources—the creeds Paul quotes—already worship Him as divine, and Paul treats those creeds as authoritative revelation.

From the beginning, the church bowed to a divine Christ, not a human teacher slowly exalted by legend.

Measured by that apostolic standard, the Nazarenes remained faithful to the original confession, honoring Paul’s letters and the earliest creeds.

The Ebionites, however, altered the Gospels, repudiated Paul, and rejected the Philippians 2 creed, denying Christ’s divinity and placing themselves outside the apostolic faith.

11. Dating the Gospels

Critical scholars commonly date Mark around AD 70, arguing that Jesus’ prophecy of the Temple’s destruction must have been written after it happened.

But this logic assumes that prophecy is impossible—a philosophical bias, not a historical fact.

If prophecy is real, the foundation for late dating collapses.

Even on their own terms, critics face contradictions.

They argue that Matthew copied Mark and therefore must be later, yet the Ebionites were already using and editing Matthew shortly after Jerusalem’s fall.

If Matthew was being altered in the 70s, it had to exist before then—and if Matthew depended on Mark, Mark must be earlier still.

The evidence forces the Synoptic Gospels back into the 60s or even 50s—within the lifetime of eyewitnesses.

Paul’s letters tighten the timeline further.

In 1 Corinthians, written about AD 54–55, Paul quotes Gospel material three times:

- 1 Corinthians 7:10 echoes Mark 10:11–12 on divorce — “not I, but the Lord.”

- 1 Corinthians 9:14 recalls Luke 10:7 — “the Lord commanded that those who proclaim the gospel should get their living by the gospel.”

- 1 Corinthians 11:23–25 recounts the words of institution at the Lord’s Supper, matching Luke 22:19–20 and Matthew 26:26–28.

These parallels show that the Gospel traditions were already written—or at least formally fixed—by the early 50s.

Paul quotes them as Scripture, not rumor, expecting his readers to recognize their authority.

This means the Gospels, or their written sources, predate 1 Corinthians itself—placing them within twenty years of the crucifixion.

Thus the timeline of Christian testimony runs not forward into myth but backward into eyewitness memory:

- Creeds (AD 30s): the original confession of Christ’s death, resurrection, and divine status.

- Paul’s Epistles (AD 48–61): the interpretation of those events by Paul himself, written within the lifetime of the apostles.

- Synoptic Gospels (AD 50s–60s): the written preservation of what the eyewitnesses had proclaimed from the beginning.

When the evidence is allowed to speak for itself, it shows that the worship of Jesus as divine and the written record of His life both originate within living memory of His death and resurrection.

Even those who date the Gospel of John later, around the 90s, acknowledge that the Synoptics—and the faith they record—were already established decades earlier.

Christianity’s foundation is not legend developed over centuries—it is history written by witnesses and verified by worship.