40% Growth Then, 5% Growth Now — What We Must Learn Anew

The Flavian dynasty ruled through power, not peace.

Under Vespasian (r. AD 69-79) and Titus (r. AD 79-81), Judea lay in ruins, the fiscus Judaicus taxed every survivor, and coins still proclaimed “Judaea Capta.”

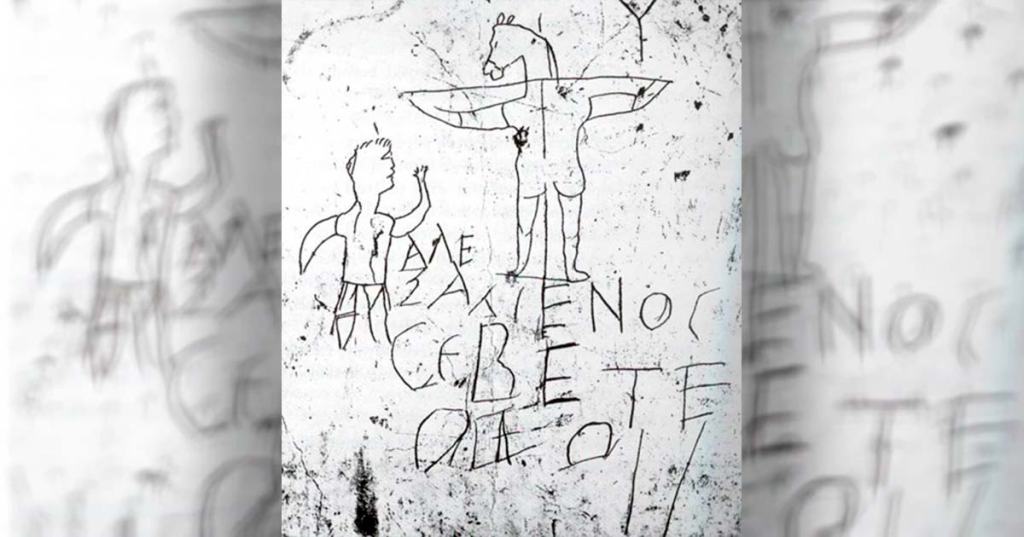

Jewish and Gentile believers alike lived under suspicion — bearing the stigma of rebellion and the memory of a crucified Messiah.

Now Domitian (r. AD 81-96), the younger brother of Titus, revives Caligula’s arrogance by seeking worship in his own lifetime and Nero’s cruelty by punishing believers for their name alone.

The same empire that built the Arch of Titus now builds temples to the living emperor and demands that the churches of Asia call him Lord and God.

Domitian’s Claim: “Our Lord and God”

Suetonius (c. AD 110–120), Life of Domitian 13.2

“He even dictated a circular letter in the name of his procurators, beginning: ‘Our Lord and God commands that this be done.’”

Cassius Dio (c. AD 220), Roman History 67.4.7

“He was not only bold enough to boast of his divinity openly, but compelled everyone to address him as ‘Lord and God.’ Such was the measure of his folly and conceit.”

Cassius Dio 67.13.4–5

“He delighted in being called both God and Lord, and slew those who refused to worship him. He destroyed the noblest of the senators and exiled many others. Finally his cruelty increased to such a degree that he executed his cousin Flavius Clemens and banished his wife Domitilla on the charge of atheism.”

Dio records this practice twice — first as a portrait of Domitian’s vanity and again when listing executions for those who refused his divine titles.

Neither Dio nor Suetonius names “Christians,” but their use of atheism and refusal of worship describes exactly what believers faced.

| Side | Inscription | Translation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | DOMITIA AVGVSTA IMP DOMITIANI AVG P P | “Domitia Augusta, wife of Emperor Domitian, Father of the Fatherland.” | Honors the empress. |

| Reverse | DIVI CAESAR IMP DOMITIANI F | “The Divine Caesar, son of Emperor Domitian.” | Commemorates their deceased and deified son as a celestial being. |

At the same time, John’s Gospel — written in these same years — records the opposite confession:

“Thomas answered and said to Him, ‘My Lord and my God.’” — John 20:28

That exact combination of titles (Lord and God) appears nowhere else in Scripture.

John uses it deliberately, crafting an independent witness to the risen Christ while also confronting the imperial claim of his own day.

What Rome demanded by law, the disciple proclaimed freely to Jesus alone.

Further, Clemens and his wife Domitilla were branded atheists, most likely for being Christians. Very few other people groups were labeled that title, besides Jews and Christians.

Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.18.4 (c. 310):

“In Domitian’s time there were many testimonies for Christ, among them Flavia Domitilla, daughter of a sister of Flavius Clemens, one of the consuls of Rome. She was exiled with many others to the island of Pontia because of her testimony to Christ.”

They were the first imperial converts and martyrs we know of. The Domitilla Catacombs in Rome, one of the earliest Christian cemeteries, are traditionally said to have been founded on her estate.

Imperial Worship in the Cities of Revelation

Temples, coins, and inscriptions from Ephesus, Pergamum, Smyrna, and Sardis show how completely the imperial cult surrounded the earliest believers.

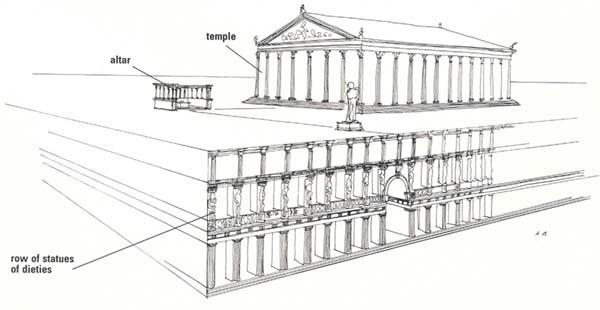

Ephesus – Temple of the Flavian Family (c. AD 89–92)

Temple Dedication (IGR IV 1453 = Ephesos Inschriften 302)

“To the Flavian family — the people of Ephesus dedicate [this temple].”

Carved across the marble architrave of the temple at Domitian Square, the inscription identified a sanctuary built for a living ruler.

Fragments of a colossal 23 foot cult statue show the emperor grasping a spear, the symbol of divine authority.

Every citizen walking through the agora looked up at a god in human form.

Pergamum – “Where Satan’s Throne Is” (c. AD 90)

Long before Domitian, Pergamum had been the birthplace of imperial worship in Asia.

In 29 BC it won a provincial competition to build the first temple to Rome and Augustus (Tacitus, Annals 4.37), and from then on the city was known as neokoros — guardian of the imperial cult.

Its acropolis towered above the Caicus Valley, layered with shrines to Athena, Asclepius, Dionysus, and Zeus Soter (“Zeus the Savior”). When the Flavians rose to power, Pergamum naturally added Domitian to its pantheon.

Dedication Inscription (IGR IV 292, c. AD 90)

Marble base found on the upper acropolis, about 50 m from the great altar precinct.

“To the God Domitian Augustus, Conqueror of the Germans.”

The block supported a statue of Domitian in the forecourt of the imperial temple beside the sanctuary of Zeus.

Provincial Coin Series (RPC II 941–947)

Obverse: “Domitian Caesar Augustus Germanicus.”

Reverse: “The People of Pergamum [to] the August God.”

Design: Domitian radiate — the sun-crowned symbol of divinity.

To citizens, the temple and its gleaming altar celebrated Rome’s salvation; to Christians, it was “Satan’s throne” (Revelation 2:13) — the visible seat of a power demanding the worship that belonged to Christ alone.

Smyrna – Divine Lineage and Public Honors (c. AD 90–95)

Statue Base (IGR IV 1431)

“To the Emperor Caesar Domitian Augustus Germanicus, son of the Divine Vespasian; the Council and People of Smyrna dedicate [this statue], honoring him as Savior and Benefactor.”

Domitian is called both son of the Divine Vespasian and Savior — titles Christians had already learned to reserve for Jesus.

Sardis – “The God, Savior and Benefactor” (c. AD 90–95)

Bilingual Stele (IGR IV 1412, Greek and Latin)

“The Council and People of Sardis dedicate [this to] Domitian Augustus the God, Savior, and Benefactor of the City.”

This inscription was carved on a bilingual marble stele, a rectangular stone slab erected near the Temple of Artemis in Sardis.

Both Greek and Latin texts appear so that local citizens and Roman officials could each read the same dedication — Greek for the provincial population who spoke it daily, Latin for the imperial administrators who governed in Caesar’s name.

The message is identical in both languages: Sardis publicly honored Domitian as God, Savior, and Benefactor.

Such stelae were placed in busy civic spaces and along procession routes where citizens gathered for festivals. They proclaimed the emperor’s divinity in both the religious language of the Greek East (theos sōtēr kai euergetēs) and the political Latin of Rome (Deus Salvator et Benefactor).

It is a literal monument to the union of religion and empire — stone evidence that civic loyalty had become a form of worship.

Every oath, every festival, every public feast reinforced Domitian’s divine status; refusal to take part was treated as disloyalty, even treason.

Economic Pressure and the Mark of the Beast

“No one could buy or sell except the one who had the mark or the name of the beast.” — Revelation 13:17

In John’s day, religion and commerce were one system.

Every trade in Asia belonged to guilds that held banquets in temples, offered sacrifices to the gods, and poured libations to Caesar. Joining meant worship.

Inscriptions from Asia Minor show how this worked:

- Ephesus: The Silversmiths’ Guild dedicated altars to Artemis and the emperor (Acts 19:23–27).

- Pergamum: Tanners and dyers sacrificed “for the welfare of the emperor.”

- Sardis: Merchants funded games “for the safety of Caesar.”

- Smyrna: Associations built banquet halls “to the August gods.”

One inscription from Ephesus reads:

“To the August gods and to the Genius of the Emperor, the Bakers dedicate this offering.” (CIL III.7089)

Even money was the emperor’s medium. Coins carried his image — often radiate like the sun — and titles such as divus (“divine”) and soter (“savior”).

To buy or sell was to use the emperor’s likeness as a seal of trust.

The word John uses for “mark” — charagma — was the common term for a stamp on a coin or a brand on a slave or soldier. It meant visible ownership or allegiance. In that sense, the “mark of the beast” was the imperial stamp of belonging — the economic and symbolic sign that a person recognized Caesar as lord.

Coins from Domitian’s reign reinforced this imagery: his head encircled with rays, his titles naming him “divine lord and god,” and reverses showing him seated on a globe. These marks of commerce were marks of worship. To refuse them was to lose livelihood and standing. To accept them was to surrender one’s soul.

When Jesus said, “Render to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s,” He spoke in a world where tax and worship were separate. By Domitian’s time they were not. In Judea, paying tax acknowledged Roman rule; in Asia, buying and selling itself acknowledged Caesar’s divinity.

What had once been a political payment had become a religious act.

The question was no longer “Should we pay taxes to Caesar?” but “Must we worship Caesar to live?”

The Number of the Beast and the Nero Legend

Revelation 13 ends with one of the most famous verses in the Bible:

“This calls for wisdom: let the one who has understanding calculate the number of the beast, for it is the number of a man, and his number is 666.”

— Revelation 13:18

This is gematria—a system where letters represent numbers. When “Nero Caesar” is written in Hebrew letters (נרון קסר, Neron Qesar), the total is 666. Some manuscripts of Revelation even read 616, which fits the Latin spelling “Nero Caesar” without the final n.

This shows the beast first pointed to Nero, remembered as the emperor who initiated state persecution of Christians. But why would John use Nero’s name when writing 25–30 years later under Domitian?

Because Romans themselves believed Nero was not really gone.

Dio Chrysostom: “Even Now Everybody Wishes He Were Still Alive”

Dio Chrysostom (writing during the reign of Domitian, c. AD 88–96) gives us the earliest surviving testimony that people still believed Nero was alive:

“For so far as the rest of his subjects were concerned, there was nothing to prevent his continuing to be Emperor for all time, seeing that even now everybody wishes he were still alive, and the great majority do believe that he is, although in a certain sense he has died not once but often along with those who had been firmly convinced that he was still alive.”

— Dio Chrysostom, Discourses 21.10, On Beauty (c. AD 88–96)

This statement, written less than thirty years after Nero’s death, proves that belief in Nero’s survival was already widespread by Domitian’s day. Dio’s tone suggests that many in the empire—perhaps nostalgically—still longed for Nero’s return.

Tacitus: The First False Nero (AD 69)

Tacitus (writing c. AD 105) records that, scarcely a year after Nero’s death, an impostor appeared in Greece:

“About this time, a man of mean origin appeared, who gave out that he was Nero. By his voice and features he deceived many, and by his appearance revived the delusion which still lingered among the people that Nero was alive. He was, however, soon detected and put to death by order of the governor.”

— Tacitus, Histories 2.8 (c. AD 105)

Tacitus shows how quickly the legend took shape. The impostor’s resemblance and musical skill persuaded soldiers and civilians alike that Nero lived on.

Suetonius: The Rumor of Nero’s Return

Suetonius (writing c. AD 121) confirms that belief in Nero’s return persisted for decades and even caused near-war between Rome and Parthia:

“Even after his death there were many who for a long time decorated his tomb with spring and summer flowers, and now again there were others who put up his statues on the Rostra in the toga praetexta and issued edicts in his name as if he were alive. Twenty years later another pretender appeared, supported by the Parthians, and nearly brought on war between them and us before he was handed over.”

— Suetonius, Life of Nero 57 (c. AD 121)

For Suetonius, the legend was no harmless rumor. It stirred real movements, edicts, and political tension—evidence of how deeply the idea of Nero’s return had entered Roman imagination.

Cassius Dio: Terentius Maximus and the Parthian Refuge

Cassius Dio (writing early 3rd century AD) recounts another impostor—this one named Terentius Maximus—who gained the backing of Rome’s eastern rival:

“In the reign of Titus there arose another man who claimed to be Nero; his name was Terentius Maximus. He resembled Nero in face and voice, and, like him, sang to the lyre. By these means he drew many after him, and, when pursued, fled to the Parthians. There he was treated with great honour, but later he was detected and put to death.”

— Cassius Dio, Roman History 66.19.3 (written c. AD 210)

Dio also remarks more generally that “many pretended to be Nero, and this caused great disturbances.” The episode demonstrates how enduring and politically volatile the Nero Redivivus expectation had become.

Domitian as a “New Nero”

Finally, Dio draws a direct moral parallel between Nero and Domitian himself:

“He was a man of Nero’s type, cruel and lustful, but he concealed these vices at the beginning of his reign; later, however, he showed himself the equal of Nero in cruelty.”

— Cassius Dio, Roman History 67.1–2 (written c. AD 210)

By Dio’s time, Nero had become the enduring archetype of a tyrant—one whose spirit seemed to live again in later emperors, and whose rumored return continued to haunt the Roman world.

The “Synagogue of Satan” and Jewish Tax Pressure

John’s letters to the churches in Smyrna and Philadelphia (Revelation 2–3) reveal that persecution in Asia Minor came not only from Roman authorities but also from certain local Jewish communities that publicly opposed the followers of Jesus.

Revelation 2:9

“I know your tribulation and your poverty (but you are rich) and the slander of those who say they are Jews and are not, but are a synagogue of Satan. Do not fear what you are about to suffer. Behold, the devil is about to throw some of you into prison, that you may be tested, and for ten days you will have tribulation. Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life.”

Revelation 3:9

“Behold, I will make those of the synagogue of Satan who say that they are Jews and are not, but lie—behold, I will make them come and bow down before your feet, and they will learn that I have loved you.”

In both cases, John’s audience lived under Domitian’s enforcement of the Jewish tax (fiscus Judaicus).

Jewish leaders throughout the empire were required to clarify who qualified as Jewish and owed the tax.

Believers in Jesus—claiming Jewish heritage but refusing to pay—were denounced as impostors and stripped of their legal protection as part of a religio licita (a permitted religion).

Such denunciations easily became “slander” (blasphēmia), leading to arrests, confiscation of property, and martyrdom.

John’s phrase “synagogue of Satan” does not condemn Judaism as a whole.

It identifies a local assembly of accusers—people whose actions aligned with Rome’s efforts to suppress the Church.

In Revelation’s theology, Satan is “the accuser of our brothers” (Rev 12:10).

Thus, anyone who brought legal accusations against Christians became, in John’s language, part of “the synagogue of the accuser.”

Persecution was both earthly and spiritual—a human partnership in the devil’s cosmic war against Christ’s people.

This reality soon reappeared in history.

About sixty years later, John’s prophecy was fulfilled in Smyrna during the martyrdom of Polycarp, the city’s aged bishop and a disciple of the Apostle John.

The Martyrdom of Polycarp 13.1:

“The Jews, as was their custom, were the most eager in bringing wood for the fire.”

The same city where John wrote of “the synagogue of Satan” became the stage for its fulfillment: a righteous man condemned by Roman officials and cheered to his death by his own countrymen.

Yet the words of Revelation endured:

“Be faithful unto death, and I will give you the crown of life.”

Polycarp’s martyrdom stands as living proof that John’s vision described real events, not abstract prophecy.

In Smyrna, the Church triumphed through endurance—refusing fear, sharing in Christ’s suffering, and gaining the crown promised by the risen Lord.

Nerva’s Reforms and the Return of Freedom

Cassius Dio 68.1–2:

“Nerva also released those who had been convicted of impiety under Domitian and forbade any further accusations of that kind. He restored to the exiles their property, recalled those who had been banished, and burned publicly the secret reports of informers.”

Suetonius, Life of Nerva 3.1–2:

“He swore that no one should ever be punished for impiety or insult to the emperor. He forbade the bringing of charges under the laws of treason and recalled all who had been condemned for such offenses.”

Pliny, Panegyricus 58–59 (AD 100):

“This oath first Nerva took, and by it he restored freedom to the Senate.”

Nerva’s coins proclaimed the same spirit of clemency:

- FISCI IVDAICI CALVMNIA SVBLATA — “The false accusation of the Jewish tax removed.”

- LIBERTAS PVBLICA — “Public freedom restored.”

- IVSTITIA AVGVSTI — “The justice of the emperor.”

| Side | Inscription | Translation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obverse | IMP NERVA CAES AVG PM TR P COS III PP | “Emperor Nerva Caesar Augustus, High Priest, holder of tribunician power, Consul for the third time, Father of the Fatherland.” | Honors Nerva’s authority and civic leadership. |

| Reverse | AEQVITAS AVGVST | “The Equity of the Emperor.” | Symbol of fair governance and economic stability under Nerva. |

These reversals ended Domitian’s oppressive tax policies that had ensnared Jews and Jewish Christians alike.

Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.20.9:

“After the tyrant’s death, John returned from his exile and took up residence again in Ephesus.”

For the first time in decades the Church could breathe. John returned from Patmos, and in that calm the final apostolic writings were completed and the Church clarified its faith against new distortions.

John’s Writings and Their Historical Context

| Work | Approx. Date | Place | Ancient Sources | Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gospel of John | 85–95 | Ephesus | Irenaeus 3.1.1 (c. 180) | Before exile under Domitian | Proclaims Jesus as eternal Logos against Greek dualism and emperor worship |

| 1 John | 90–95 | Ephesus | Internal evidence | Pre-exile warning against Docetism | Affirms that Christ came “in the flesh.” |

| 2 & 3 John | 90–95 | Ephesus | Early tradition | Letters to Asia churches | Warns against deceivers. |

| Revelation | 95–96 | Patmos | Irenaeus 5.30.3; Eusebius 3.18 | Exile under Domitian | Calls for endurance under imperial idolatry. |

| Return to Ephesus | 96 | Ephesus | Eusebius 3.20.9 | Released by Nerva | Resumed leadership of Asia churches. |

| Death of John | 98–102 | Ephesus | Irenaeus 2.22.5; Polycrates in Eusebius 3.31.3 | Reign of Trajan | Last apostle dies in peace. |

Why John Had to Write — From Judea to the Greek World

| Context | Region | Key Figures | Central Issue | John’s Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Jewish-Christian Era (30–70 AD) | Judea | Nazarenes (orthodox); Ebionites (heretical) | Could a Jewish man be divine? Ebionites denied Christ’s pre-existence and rejected Paul. | “In the beginning was the Word … and the Word was God.” (1:1) |

| Greek World (80–100 AD) | Asia Minor / Ephesus | Cerinthus and early Docetists | Could the divine truly become flesh and suffer? | “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” (1:14) |

In Judea the debate was whether Jesus could be divine; in Ephesus it was whether He could be truly human. John’s Gospel and letters address both—the eternal God who became man and suffered in the flesh.

The First Christians and the New Distortions

The first denomination within Christianity were the Nazarenes, Jewish Christians who kept the Law yet worshiped Jesus as the divine Son of God. They were essentially the losing party of the Acts 15 church council.

Epiphanius, Panarion 29.7.2–4 (c. 375):

“They use both the Old and New Testaments … They acknowledge that Jesus is the Son of God and that He suffered for the salvation of the world.”

Jerome, Commentary on Isaiah 9.1 (c. 400):

“The Nazarenes accept the Messiah … as the Son of God and say that He was born of the Virgin Mary.”

By contrast, the Ebionites denied Christ’s divinity, rejected Paul, and altered Matthew to remove the virgin birth.

Cerinthus and the First Docetists

Epiphanius, Panarion 28.1–2 (c. 375):

“Cerinthus, trained in the wisdom of the Egyptians, came to Asia and taught that the world was not made by the supreme God but by a certain Power very far removed from Him.”

Hippolytus, Refutation of All Heresies 7.33 (c. 225):

“He was educated in the knowledge of the Egyptians and imbibed their teaching, but he boasted that an angel had appeared to him and revealed these things.”

Irenaeus, Against Heresies 1.26.1 (c. 180):

“He represented Jesus as not born of a virgin, but as the son of Joseph and Mary … The Christ descended upon Him at His baptism and afterward left Him before the Passion.”

Eusebius, Hist. eccl. 3.28.2 (c. 310):

“Cerinthus, by means of revelations which he pretended were written by a great apostle, brought before us fables of his own invention, stating that after the resurrection the kingdom of Christ would be on earth … Being a lover of the body and altogether carnal, he dreamed that the kingdom of Christ would consist of eating and drinking and marrying.”

Caius of Rome (c. 200) and Dionysius of Alexandria (3rd cent.) reported that some believed Cerinthus had written or re-used Revelation to teach a sensual earthly kingdom.

Cerinthus’s teaching (AD 80–100) asserted a lower creator god, a temporary Christ-spirit, and a carnal millennium of pleasure. John’s Gospel answers each point.

| Cerinthus’s Claim | John’s Counter-Statement |

|---|---|

| A lesser power made the world. | “All things were made through Him.” (1:3) |

| Jesus was only a man. | “The Word became flesh.” (1:14) |

| The Christ-spirit left before the cross. | “When Jesus knew that all was now finished, He said, ‘It is finished.’” (19:30) |

| The divine cannot touch matter. | “He showed them His hands and His side.” (20:20) |

| The kingdom is earthly pleasure. | “My kingdom is not of this world.” (18:36) |

The Emerging Docetic Worldview — Primary Sources from the Nag Hammadi Texts

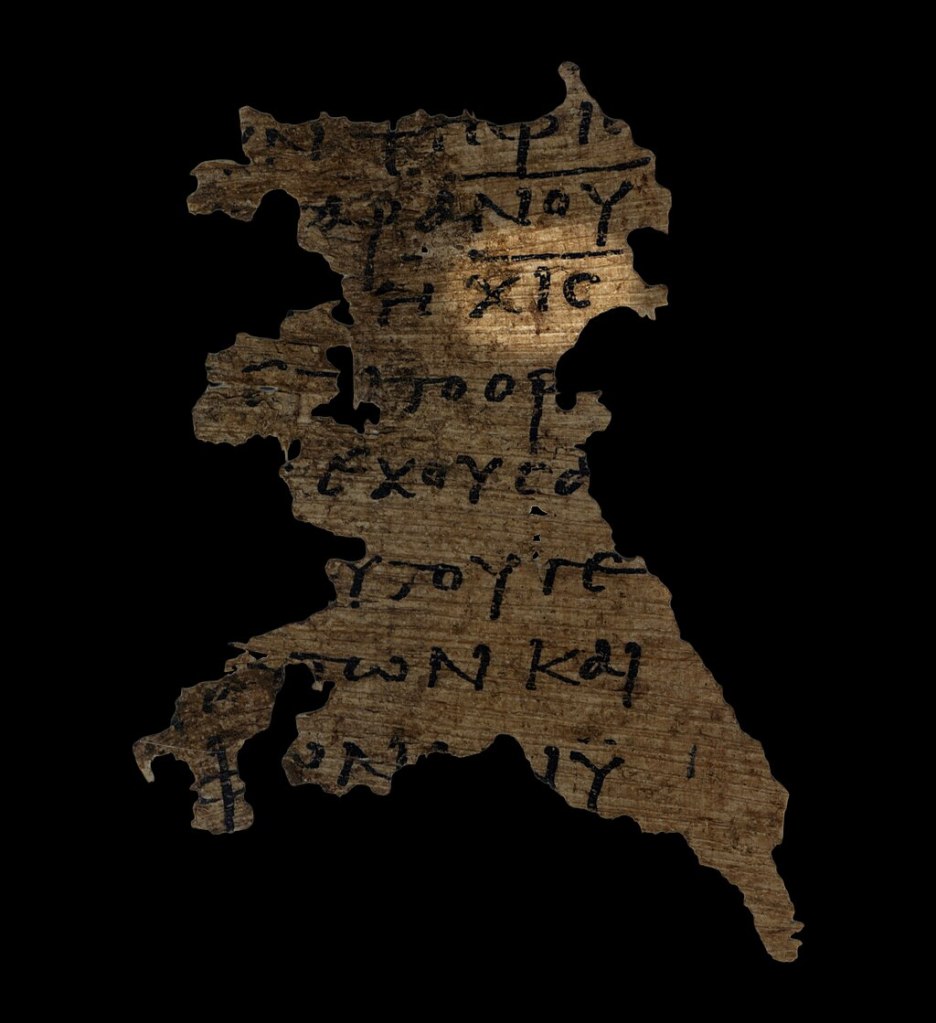

By the end of the first century dualistic ideas spread through Egypt and Syria. The Nag Hammadi Library (copied 4th cent., written 80–150 AD) preserves the teachings John was opposing.

Apocryphon of John (c. 100–120, Egypt/Syria):

“The ruler said, ‘I am God and there is no other beside me,’ for he did not know the source from which he had come. … And the archons created the seven heavens and their angels and made a mold of a man.” (11.18–12.10)

A lesser god creates and rules the world—what John denies when he writes, “All things were made through Him.” (1:3)

Gospel of Thomas (c. 100–120, Syria):

“These are the secret sayings that the living Jesus spoke.… Whoever discovers the interpretation of these sayings will not taste death.” (1)

“The kingdom is inside of you and outside of you.… When you come to know yourselves, then you will be known.” (3)

“When you make the two one … and make the male and the female one and the same, then you will enter the kingdom.” (22)

Thomas borrows many sayings from Matthew, Mark, and Luke but omits the cross and resurrection. Salvation comes through self-knowledge and escaping the material world. John answers: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.” (1:14)

Gospel of Truth (c. 120–140, Alexandria/Rome):

“The Word of the Father came into the midst of those who were oblivious, death having taken them captive.… He was nailed to a tree, and He became a fruit of the knowledge of the Father. But He did not suffer as they thought, for His suffering was only in appearance.” (22–23)

Here Christ’s crucifixion is only symbolic, a parable of knowledge. John responds as an eyewitness: “Blood and water came out … He who saw it has borne witness.” (19:34–35)

Second Treatise of the Great Seth (c. 120–160, Egypt):

“It was another, their father, who drank the gall and the vinegar; it was not I.… It was another, Simon, who bore the cross on his shoulder.… For my death, which they think happened, happened to them in their error and blindness.” (55.15–30)

Here Christ denies His own crucifixion and substitutes another in His place—a direct denial of the incarnation and atonement. John writes: “When He had received the sour wine, He said, ‘It is finished.’” (19:30)

Gospel of Judas (c. 130–160, Egypt):

“Often He did not appear to His disciples as Himself, but He was found among them as a child.” (33.10–11)

“Come, that I may teach you about the mysteries no person has ever seen.… From the cloud there appeared an angel … His name was Nebro, which means ‘rebel’; others call him Yaldabaoth.… Nebro created six angels as his assistants.” (47.1–9; 51.1–8)

“And Saklas said to his angels, ‘Let us create a human being after the likeness and the image.’” (52.10–11)

“You will exceed all of them, for you will sacrifice the man that clothes me.” (56.18–20)

In this text Jesus is a shapeshifter whose body is illusory; lower angels rule creation and imitate Genesis by creating humanity; Judas becomes the hero who frees Jesus from His body. John answers: “All things were made through Him … The Word became flesh.” (1:3, 14)

The Church’s Early Defense and the Apostolic View of Christ — The God-Man in the Generation After John

Within a decade of John’s death, the next generation of Christian leaders—men who had known the apostles or their immediate disciples—carried forward the same confession:

Jesus Christ is both fully God and fully man—our Lord and our God.

Their writings show that this was not a later development but the defining belief of the Church from the beginning.

Ignatius of Antioch

(c. AD 110, on his way to martyrdom under Trajan)

Facing execution in Rome, Ignatius wrote seven letters to the churches of Asia, echoing John’s theology and refuting those who denied the incarnation.

Ignatius, Smyrnaeans 2.1:

“He truly suffered, not as certain unbelievers say, that He suffered in appearance only. They themselves exist only in appearance.”

Ignatius, Trallians 10.1:

“Be deaf whenever anyone speaks apart from Jesus Christ, who was of the race of David, who was truly born, and who was truly crucified.”

Ignatius’s faith is emphatically Johannine—insisting that the Word truly became flesh, was truly born, and truly crucified.

To him, salvation depends on the reality of the incarnation, not a symbolic or apparent suffering.

He also confesses the unity of God and Man in Christ with stunning clarity:

Ignatius, Ephesians 7.2:

“There is one Physician, fleshly and spiritual, born and unborn, God in man, true Life in death, both from Mary and from God, first passible and then impassible—Jesus Christ our Lord.”

Ignatius’s phrase “God in man” perfectly captures the apostolic view: the eternal, impassible God entering history through the passible flesh of Jesus.

This was the Church’s defense against both Greek Docetism and Jewish unbelief.

Polycarp of Smyrna

(c. AD 110–115)

Polycarp, To the Philippians 12:

“Now may the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, and the eternal High Priest Himself, the Son of God, Jesus Christ, build you up in faith and truth … to all who shall believe on our Lord and God Jesus Christ and on His Father who raised Him from the dead.”

Polycarp—John’s disciple—echoes Thomas’s confession in John 20:28, directly calling Jesus “our Lord and God.”

He presents Christ as both divine and incarnate: the eternal High Priest who ministers for humanity because He shares humanity, yet who is worshiped as God because He is divine.

Epistle of Barnabas

(c. AD 100–130, Alexandria or Syria)

Barnabas 5.6–9:

“If the Lord endured to suffer for our soul, though He is Lord of the whole earth, to whom God said before the foundation of the world, ‘Let us make man in our image and after our likeness,’ understand how it was that He endured to suffer at the hands of men.… The Son of God came in the flesh that He might abolish death and show forth the resurrection from the dead.”

Barnabas 12.10:

“The Lord submitted Himself to suffer for us, though He is God, and He fulfilled the promises made unto the fathers.”

Barnabas affirms that the Creator Himself—the one who made humanity in His image—entered His own creation to suffer and redeem it.

His words match both Paul’s Christ Hymn (Philippians 2:6–11) and John’s Prologue (John 1:1–14): the same God who made the world became flesh to save it.

Letter to Diognetus

(c. AD 120–150, probably Asia Minor)

Diognetus 7.2–4; 9.2:

“He Himself sent His own Son—as God He sent Him, as to men He sent Him; as Savior He sent Him, as persuader, not as tyrant.… He appeared as God, yet in humility among men.

For what else was able to cover our sins but His righteousness? In whom else could we, lawless and ungodly men, have been made righteous except in the Son of God alone?”

The Letter to Diognetus presents the incarnation as a divine visitation:

God appearing among men, clothed in humility yet possessing full deity.

It summarizes in prose what John had written poetically: “The Word became flesh and dwelt among us.”

Unified Testimony

| Source | Date | Confession of Christ |

|---|---|---|

| Ignatius – Ephesians 7; Smyrnaeans 2 | 105–110 | “One Physician, fleshly and spiritual… God in man.” / “He truly suffered, not in appearance only.” |

| Polycarp – Philippians 12 | 110–115 | “Our Lord and God Jesus Christ.” |

| Barnabas 5 & 12 | 100–130 | “The Son of God came in the flesh… though He is God.” |

| Letter to Diognetus 7 & 9 | 120–150 | “He appeared as God, yet in humility among men.” |

These writings span the first half of the second century—from Antioch to Smyrna, from Alexandria to Asia Minor—and they all speak with one voice.

The earliest post-apostolic Church proclaimed not a developing theology but the same truth John had written on Patmos and in Ephesus:

The Creator Himself became flesh to redeem His creation.

The Word who was with God and was God truly lived, truly suffered, and truly rose as the God-Man Jesus Christ.

Trajan to Pliny: An Old Law, Not a New One

When Trajan became emperor in AD 98, the Church had already suffered under three emperors.

No new law was introduced; Nero’s precedent of AD 64 still governed imperial practice:

to be called a Christian was itself a crime.Under Nero, believers had been executed “for the name.” (Tacitus, Annals 15.44)

Under Domitian, prosecutions resurfaced under charges of “impiety.”

Under Nerva, there was brief relief.

Under Trajan, the old principle remained.What changes here is not policy but evidence: for the first time, we possess imperial correspondence showing how the precedent worked in practice.

Pliny’s Letter to Trajan (AD 111–113)

Author: Gaius Plinius Caecilius Secundus (Pliny the Younger), governor of Bithynia-Pontus.

Source: Letters 10.96 (Loeb translation).

Setting: Pliny had newly arrived in the province and discovered that Christian trials were already taking place.

He had never presided over one and sought clarification from the emperor.

Pliny’s Letter (Full Text)

“It is my rule, Sir, to refer to you all matters concerning which I am in doubt.

For who is better able either to direct my hesitation or to instruct my ignorance?

I have never been present at any trials of Christians; therefore I do not know what is the customary subject-matter of investigations and punishments, or how far it is usual to go.

Whether pardon is to be granted on repentance, or if a man has once been a Christian it does him no good to have ceased to be one;

whether the mere name, apart from atrocious crimes associated with it, or only the crimes which adhere to the name, is to be punished—all this I am in great doubt about.“In the meantime, the course that I have adopted with respect to those who have been brought before me as Christians is as follows:

I asked them whether they were Christians.

If they admitted it, I repeated the question a second and a third time, with a warning of the punishment awaiting them.

If they persisted, I ordered them to be led away for execution; for I could not doubt that, whatever it was that they admitted, that stubbornness and unbending obstinacy ought to be punished.

There were others similarly afflicted; but, as they were Roman citizens, I decided to send them to Rome.“In the case of those who denied that they were or had been Christians, when they invoked the gods in the words I dictated and offered prayer with incense and wine to your image—which I had ordered to be brought for this purpose together with statues of the gods—and furthermore cursed Christ (none of which things, it is said, those who are really Christians can be forced to do), I thought they ought to be discharged.

Others, who were named by an informer, first said that they were Christians and then denied it; true, they had been of that persuasion, but they had left it, some three years ago, some more, and a few as much as twenty years.

All these also worshiped your image and the statues of the gods, and cursed Christ.“They maintained, however, that the sum and substance of their fault or error had been that on a fixed day they were accustomed to meet before daylight and to recite by turns a form of words to Christ as to a god,

and that they bound themselves by an oath—not for any crime, but not to commit theft, robbery, or adultery, not to break their word, and not to refuse to return a deposit when called upon to restore it.

After this it was their custom to separate, and then meet again to partake of food—but ordinary and harmless food.

Even this they said they had ceased to do after the publication of my edict, by which, in accordance with your instructions, I had forbidden associations.“I thought it the more necessary, therefore, to find out what was true from two female slaves, whom they call deaconesses, by means of torture.

I discovered nothing else but depraved, excessive superstition.

Therefore I postponed the investigation and hastened to consult you.

The matter seems to me to justify consultation, especially on account of the number of those in danger;

for many of every age, every rank, and also of both sexes are already and will be brought into danger.

For the contagion of this superstition has spread not only through cities, but also through villages and the countryside;

and yet it seems possible to check and cure it.

It is certain at least that the temples, which had been almost deserted, have begun to be frequented again, and the sacred rites, long suspended, are again being performed, and there is a general demand for the flesh of sacrificial victims, for up till now very few purchasers could be found.

From this it may easily be supposed what a multitude of people can be reclaimed, if only room is granted for repentance.”

Key Insights from Pliny’s Letter

1. Trials Were Already Ongoing

Pliny says, “I have never been present at any trials of Christians,” revealing that such trials preceded him. He is not initiating persecution but ensuring he follows existing imperial practice.2. The “Forbidden Associations”

Pliny’s comment that he forbade Christian gatherings follows Trajan’s earlier ban on all private associations (collegia).

In a nearby letter (Letters 10.33–34a), Pliny had asked to form a fire brigade in Nicomedia, but Trajan refused, warning that “whatever name we give them, and for whatever purpose they are formed, they will not fail to degenerate into political clubs.”

Because of this standing order, Christian meetings were automatically illegal as unauthorized associations.

Thus, their assemblies were viewed as civic threats, not religious services.3. “Stubbornness and Unbending Obstinacy” (pertinacia)

Romans considered blind persistence a moral failing—an assault on civic order.

Writers like Cicero and Seneca called pertinacia (stubborn defiance) a kind of madness, the opposite of the Roman virtue of moderation (moderatio).

To confess Christ three times in defiance of a magistrate’s warning was seen as treasonous pride, not conscience.

Hence Pliny’s statement that such obstinacy “ought to be punished” reflects Rome’s moral worldview, where social harmony outweighed individual conviction.4. The Reputation of True Christians

Pliny records that those who truly belonged to the movement “can never be forced to curse Christ.”

This is an extraordinary pagan admission: even Rome’s officials recognized that real Christians were unfailingly loyal to Christ.

It became, unintentionally, a mark of authenticity: apostates could perform sacrifices, but the faithful could not.

Martyrdom, therefore, was not fanaticism—it was simply consistency with known Christian behavior.5. Worship of Christ “as to a God”

Pliny confirms that believers “sang a hymn to Christ as to a god.”

This line—written by a pagan witness scarcely 80 years after the crucifixion—proves that the earliest Church universally worshiped Jesus as divine.

It is an unintentional historical echo of Thomas’s words in John 20:28: “My Lord and my God.”6. Pliny’s Attitude

Pliny is no sadist; he sees Christianity as a “superstition”—a misguided enthusiasm that disrupts civic order.

His tone combines administrative irritation and genuine bewilderment: how could such moral people be so disloyal to the gods?

It is the first documented Roman attempt to rationalize persecution as social hygiene.7. The Scope of the Faith

Pliny’s line that “the contagion has spread through cities, villages, and the countryside” reveals how pervasive Christianity had become by AD 110.

Even pagan temples, he notes, were deserted because of it.

Trajan’s Reply (Full Text, AD 112)

Source: Letters 10.97 (Loeb Translation)

“You have followed the right course, my dear Secundus, in examining the cases of those who had been denounced to you as Christians;

for it is impossible to lay down any general rule which will apply as a fixed standard.

They are not to be sought out; if they are brought before you and convicted, they must be punished.

With this proviso, however—that if anyone denies that he is a Christian and proves it by worshiping our gods, he is to obtain pardon through repentance, even if he has incurred suspicion in the past.“As for anonymous accusations, they must not be admitted in any proceedings.

For that would establish a very bad precedent and is not in keeping with the spirit of our age.”

Key Insights from Trajan’s Reply

1. Not a New Law—A Confirmation of Nero’s Precedent

Trajan introduces no new principle. The “right course” Pliny had followed simply enforces the Neronian standard: the name “Christian” is punishable by death.2. Reactive, Not Proactive Persecution

“They are not to be sought out” sounds lenient but only limits administrative workload.

If accused and proven guilty, Christians were still executed. The persecution was reactive, not abolished.3. Recantation as Proof of Loyalty

Trajan’s test—offering incense to the gods—measured civic allegiance, not personal belief.

Recantation showed loyalty to Rome; refusal proved treasonous defiance.4. Imperial “Fairness”

By forbidding anonymous accusations, Trajan presents himself as a just ruler.

Yet the core remains: death for those who confess Christ.5. Continuity of Hostility

This exchange did not create a new policy.

It merely documents the ongoing enforcement of Nero’s logic—that Christianity was incompatible with Roman religious identity.

Theological Implications — The Empire Meets the God-Man

To the empire, the issue was not theology but loyalty.

To the Church, it was not loyalty but lordship.

The Christians’ refusal to curse Christ or offer incense to Caesar was their confession that the incarnate God alone deserved worship.Rome saw stubbornness; the Church saw faith.

Rome saw defiance; the Church saw fidelity.

In worshiping the Word made flesh, believers declared that no emperor could demand what belonged to God alone.“They sang a hymn to Christ as to a god.” — Pliny, Letters 10.96

That one pagan line records the Church’s heart: the same Christ whom John called “Lord and God” was still being worshiped as such, even when worship meant death.

The Church’s Call to Perseverance

The same correspondence that shows Rome’s suspicion of Christians also introduces a chorus of Christian writings calling believers to endurance under trial.

These texts come from every corner of the empire—Rome, Antioch, Smyrna, and Asia Minor—and together they reveal how the early Church met persecution not with revolt, but with perseverance, humility, and hope.

Clement of Rome (AD 95–96, writing from Rome)

1 Clement 5.2–6.1:

“Because of jealousy and strife Paul pointed out the prize of endurance; after he had been seven times in chains, had been driven into exile, had been stoned, had preached both in the East and in the West, he gained the noble renown of his faith.

Having taught righteousness unto the whole world and having reached the furthest bounds of the West, he bore witness before rulers and so departed from the world, leaving behind him an example of endurance.

To these men who lived godly lives was gathered a vast multitude of the elect who, through many indignities and tortures, furnished a brave example among us.”Clement, writing from the church at Rome to Corinth, recalls Paul’s and Peter’s martyrdoms under Nero and commends their “example of endurance.”

Already, suffering for Christ had become a mark of faithfulness across the empire.

Ignatius of Antioch (AD 110, on his way to execution in Rome)

Ignatius, Romans 4.1–2:

“I am writing to all the Churches and I enjoin all men that I am dying willingly for God’s sake, unless you hinder me.

I beseech you, do not show an unseasonable goodwill towards me.

Suffer me to become food for the wild beasts, through whom it is granted me to attain unto God.

I am God’s wheat, and I am ground by the teeth of wild beasts, that I may be found pure bread of Christ.”Ignatius, Ephesians 3.1:

“Nothing is hidden from you if you are perfect in your faith and love towards Jesus Christ, for these are the beginning and end of life—faith the beginning, love the end.

The two, in unity, are God Himself, and all things follow upon them.

No man who professes faith sins, and no man who has love hates.

The tree is made manifest by its fruit; so those who profess to belong to Christ shall be known by their actions.”Ignatius’s letters radiate the same joyful endurance that Pliny had called “obstinacy.”

For him, dying for Christ was not madness but communion with the incarnate God.

Polycarp of Smyrna (AD 155, preserving a first-century memory)

The Martyrdom of Polycarp 8.1–2; 9.3:

“The whole multitude marveled at the nobility and godly fear of Polycarp.

… When he was brought before the proconsul, he was asked to curse Christ and he said, ‘Eighty and six years have I served Him, and He has done me no wrong.

How then can I blaspheme my King who saved me?’

When he had confessed boldly that he was a Christian, the proconsul threatened to burn him with fire.

But he said, ‘You threaten me with a fire that burns for a time and is soon quenched; for you are ignorant of the fire of the coming judgment and of eternal punishment reserved for the ungodly.

But why do you delay? Bring what you will.’”Polycarp’s calm defiance encapsulates the Church’s understanding of persecution as participation in Christ’s own victory.

The Letter to the Philippians from Polycarp (AD 110–115)

Polycarp 8.2–3:

“Let us then continually persevere in our hope and the earnest of our righteousness, which is Jesus Christ, ‘who bore our sins in His own body on the tree,’

who did no sin, neither was deceit found in His mouth.

Let us therefore become imitators of His endurance, and if we suffer for His name’s sake, let us glorify Him.”Here, Polycarp explicitly ties Christian endurance to imitation of the crucified God-Man: Christ’s suffering becomes the pattern for His people.

The Epistle of Barnabas (AD 100–130)

Barnabas 7.11:

“He Himself willed to suffer, for it was necessary for Him to suffer on the tree.

For by His suffering He was to redeem us who live under the shadow of death.”Barnabas emphasizes that Christ’s own endurance sanctified human suffering, turning persecution into fellowship with the Redeemer.

Letter to Diognetus (AD 120–150, Asia Minor)

Diognetus 5.1–5:

“Christians are not distinguished from other men by country or language or customs.…

They dwell in their own countries, but only as sojourners; they share all things as citizens, and suffer all things as foreigners.

Every foreign land is their fatherland, and every fatherland a foreign land.…

They love all men, and are persecuted by all.”This anonymous writer offers perhaps the most poetic portrait of the persecuted Church—citizens of heaven living under every empire, suffering yet loving, conquered yet unconquerable.

6. The Theology of Endurance — The God-Man as Example

From Clement’s Rome to Ignatius’s Antioch, from Polycarp’s Smyrna to the unknown author of Diognetus, all the earliest Christian writers share one conviction:

the pattern of endurance was set by the incarnate Christ Himself.

Author Region Approx. Date Focus Clement of Rome Rome 95–96 Martyrs as examples of endurance. Ignatius of Antioch Syria / Asia 110 Martyrdom as imitation of “my God.” Polycarp of Smyrna Asia Minor 110–155 Perseverance as faith in the saving King. Barnabas Alexandria / Syria 100–130 Christ’s suffering sanctifies human endurance. Letter to Diognetus Asia Minor 120–150 Christians as patient citizens of heaven amid persecution. All of them write under the shadow of Roman hostility.

All of them root endurance not in moral heroism but in the incarnation itself—the belief that the eternal Word took on flesh and endured the cross.

Because Christ suffered truly, His people could suffer faithfully.

7. Closing Reflection

Pliny saw “obstinacy.”

Trajan saw “superstition.”

But the Church saw faithfulness to the God who had become man and suffered for them.From Nero’s fire to Trajan’s law, the Christians’ hymn remained the same:

“They were accustomed to meet before dawn and to sing a hymn to Christ as to a God.”

And that is the faith Rome could never silence.